GOVERNMENT AND POLITICS IN AN AGE OF DETERIORATING PROSPERITY

Though just over a month has passed since the previous article (for which apologies), work here hasn’t slackened. Rather, I’ve been concentrating on three issues, all of them important, and all of them topics where a recognition of the energy basis of the economy can supply unique insights.

The first of these is the insanity which says that no amount of financial recklessness is ever going to drive us over a cliff, because creating new money out of thin air is our “get out of gaol free card” in all circumstances.

This isn’t the place for the lengthy explanation of why this won’t work, but the short version is that we’re now trying to do for money what we so nearly did to the banks in 2008.

The second subject is the very real threat posed by environmental degradation, where politicians are busy assuring the public that the problem can be fixed without subjecting voters to any meaningful inconvenience – and, after all, anyone who can persuade the public that electric vehicles are “zero emissions” could probably sell sand to the Saudis.

And this takes us to the third issue, the tragicomedy that it is contemporary politics – indeed, it might reasonably be said that, between them, the Élysée and Westminster, in particular, offer combinations of tragedy, comedy and farce that even the most daring of theatre directors would blush to present.

From a surplus energy perspective, the political situation is simply stated.

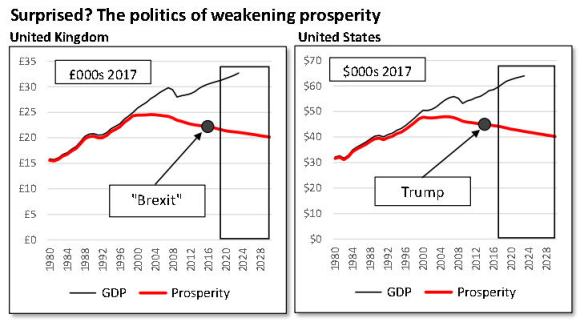

SEEDS analysis of prosperity reveals that the average person in almost every Western country has been getting poorer for at least a decade.

Governments, which continue to adhere to outdated paradigms based on a purely financial interpretation of the economy, remain blind to the voters’ plight – and, all too often, this blindness looks a lot like indifference. Much of the tragedy of politics, and much of its comedy, too, can be traced to this fundamental contradiction between what policymakers think is happening, and what the public knows actually is.

Nowhere is the gap in comprehension, and the consequent gulf between governing and governed, more extreme than in France – so that’s as good a place as any to begin our analysis.

The French dis-connection

Let’s start with the numbers, all of which are stated in euros at constant 2018 values, with the most important figures set out in the table below.

Between 2008 and 2018, French GDP increased by 9.4%, equivalent to an improvement of 5.0% at the per capita level, after adjustment for a 4.2% rise in population numbers. This probably leads the authorities to believe that the average person has been getting at least gradually better off so, on material grounds at least, he or she hasn’t got too much to grumble about.

Here’s how different these numbers look when examined using SEEDS. For starters, growth of 9.4% since 2008 has increased recorded GDP by €201bn, but this has been accompanied by a huge €2 trillion (40%) rise in debt over the same decade. Put another way, each €1 of “growth” has come at a cost of €9.90 in net new debt, which is a ruinously unsustainable ratio. SEEDS analysis indicates that most of that “growth” – in fact, more than 90% of it – has been nothing more substantial than the simple spending of borrowed money.

This is important, for at least three main reasons.

First, and most obviously, a reported increase of €1,720 in GDP per capita has been accompanied by a rise of almost €27,500 in each person’s share of aggregate household, business and government debt.

Second, if France ever stopped adding to its stock of debt, underlying growth would fall, SEEDS calculates, to barely 0.2%, a rate which is lower than the pace at which population numbers are growing (about 0.5% annually).

Third, much of the “growth” recorded in recent years would unwind if France ever tried to deleverage its balance sheet.

Then there’s the trend energy cost of energy (ECoE), a critical component of economic performance, and which, in France, has risen from 5.9% in 2008 to 8.0% last year. Adjustment for ECoE reduces prosperity per person in 2018 to €27,200, a far cry from reported per capita GDP of €36,290. Moreover, personal prosperity is lower now than it was back in 2008 (€28,710 per capita).

Thus far, these numbers are not markedly out of line with the rate at which prosperity has been falling in comparable economies over the same period. The particular twist, where France is concerned, is that taxation per person has increased, by €2,140 (12%) since 2008. This has had the effect of leveraging a 5.3% (€1,510) decline in overall personal prosperity into a slump of 32% (€3,650) at the level of discretionary, ‘left in your pocket’ prosperity.

At this level of measurement, the average French person’s discretionary prosperity is now only €7,760, compared with €11,410 ten years ago.

And that hurts.

Justified anger

Knowing this, one can hardly be surprised that French voters rejected all established parties at the last presidential election, flirting with the nationalist right and the far left before opting for Mr Macron. Neither can it be any surprise at all that between 72% and 80% of French citizens support he aims of the gilets jaunes (yellow waistcoat) protestors. “Robust” law enforcement, whilst it might just temper the manifestation of this discontent, will have the almost inevitable side-effect of exacerbating the mistrust of the incumbent government.

Because energy-based analysis gives us insights not available to the authorities, we’re in a position to understand the sheer folly of some French government policies, both before and since the start of the protests.

From the outset, there were reasons to suspect that the gloss of Mr Macron’s campaign hid a deep commitment to failed economic nostrums. These nostrums include the bizarre belief that an economy can be energized by undermining the rights and rewards of working people – the snag being, of course, that the circumstances of these same workers determine demand in the economy.

After all, if low wages were a recipe for prosperity, Ghana would be richer than Germany, and Swaziland more prosperous than Switzerland.

Handing out huge tax cuts to a tiny minority of the already very wealthiest, though always likely to be at the forefront of Mr Macron’s agenda, looks idiotically provocative when seen in the context of deteriorating average prosperity. Creating a national dialogue over the protestors’ grievances might have made sense, but choosing a political insider to preside over it, at a reported monthly salary of €14,666, reinforced a widespread suspicion that the Grand Debat is no more than an exercise in distraction undertaken by an administration wholly out of touch with voters’ circumstances.

Whilst Mr Macron has appeared flexible over some fiscal demands, he has ruled out increasing the tax levied on the wealthiest. This intransigence is likely to prove the single biggest blunder of his presidency.

Even the tragic fire at Notre Dame has been mishandled by the government, in ways seemingly calculated to intensify suspicion. Rather than insisting that the restoration of the state-owned Cathedral would be funded by the government, the authorities made the gaffe of welcoming offers of financial support from some of the most conspicuously wealthy people in France.

This prompted some to wonder when corporate logos would start to appear on the famous towers, and others to ask why, if the wealthiest wanted to make a contribution, they couldn’t have been asked to do so by paying more tax. It didn’t help that the authorities rushed to declare the fire an accident, long before the experts could possibly have had evidence sufficient to rule out more malign explanations. After all, in an atmosphere of mistrust, conspiracy theories thrive.

The broader picture

The reason for looking at the French predicament in some detail is that the problems facing the authorities in Paris are different only in degree, and not in direction or nature, from those confronting other Western governments.

The British political impasse over “Brexit”, for instance, can be traced to the same lack of awareness of what is really happening to the prosperity of the voters – whilst “Brexit” itself divides the electorate, there is something far closer to unanimity over a narrative that politicians are as ineffectual as they are self-serving, and are out of touch with real public concerns. Similar factors inform popular discontent in many other European countries, even when this discontent is articulated over issues other than the deterioration in prosperity.

At the most fundamental level, the problem has two components.

The first is that the average person is getting poorer, and is also getting less secure, and deeper into debt.

The second is that governments don’t understand this issue, an incomprehension which, to increasing numbers of voters, looks like indifference.

It has to be said that governments have no excuses for this lack of understanding. The prosperity of the average person in most Western countries began to fall more than a decade ago, and any politician even reasonably conversant with the circumstances and opinions of the typical voter ought to be aware of it, even if he or she lacks the interpretation or the information required to explain it.

Governments whose economic advisers and macroeconomic models are still failing to identify the slump in prosperity need new advisers, and new models.

A disastrous consensus

Though incomprehension (and adherence to failed economic interpretations) is the kernel of the problem, it has been compounded by the mix of philosophies adopted since the 1990s. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, an informal consensus was created in which the Left accepted the market economics paradigm, and the centre-Right tried to be ‘progressive’ on social issues.

Both moves robbed voters of choices.

Though the social policy dimension lies outside our focus on the economy, the creation of a pro-market ‘centre-Left’ has turned out to have been nothing less than a disaster. Specifically, it has had two, woefully adverse consequences.

The first was that the Left’s adoption of its opponents’ economic orthodoxy destroyed the balance of opposing philosophies which, hitherto, had kept in place the ‘mixed economy’, a model which aims to combine the best of the private and the public sector provision. The emergence of Britain’s “New Labour”, and its overseas equivalents, eliminated the checks and balances which, historically, had acted to rein in extremes.

Put another way, the traditional ‘Left versus Right’ debate created constructive tensions which forced both sides to hone their messages, as well as preventing a lurch into extremism which, whilst it might sometimes be good politics, is invariably very bad economics.

The second, of course, was that the new centre-ground – variously dubbed the “Washington consensus”, the “Anglo-American model” and “neoliberalism” – has proved to be an utterly disastrous exercise in economic extremism. One after another, its tenets have failed, creating massive indebtedness, huge financial risk and widening inequality before finally presiding over the wholesale replacement of market principles with the “caveat emptor” free-for-all of what I’ve labelled “junglenomics”.

As well as undermining economic efficiency, these developments have created extremely harmful divisions in society. Whilst Thomas Piketty’s thesis about the divergence of returns on capital and labour is not persuasive, the reality since 2008 has been that asset prices have soared, whilst incomes have stagnated. This process, which has been the direct result of monetary policy, has rewarded those who already owned assets in 2008, and has done nothing for the less fortunate majority.

There is a valid argument, of course, which states that the authorities’ adoption of ultra-cheap money during and after the 2008 global financial crisis (GFC I) was the only course of action available.

But the role of policymakers is to pursue the overall good within whatever the economic and financial context happens to be. So, when central bankers launched programmes clearly destined to create massive inflation in asset prices, governments should have responded with fiscal measures tailored to capture at least some of these gains for the unfavoured majority.

Simply put, the unleashing of ZIRP and QE made a compelling case for the simultaneous introduction of higher taxes on capital gains, complemented by wealth taxes in those countries where these did not already exist.

Failure to do this has hardened incompatible positions. Those whose property values have soared insist, often with absolute sincerity, that their paper enrichment is the product entirely of their own diligence and effort, owes nothing to the luck of being in the right place at the right time, has had nothing whatever to do with the price inflation injected into property markets (in particular) by ultra-cheap monetary policies, and hasn’t happened at the expense of others.

For any younger person, often unable to afford or even find somewhere to live, it is necessarily infuriating to be lectured by fortunate elders on the virtues of saving and hard work.

It’s a bit like a lottery winner criticizing you for buying the wrong ticket.

A workable future

The silver lining to these various clouds is that future policy directions have been simplified, with the paramount objectives being (a) the healing of divisions, and (b) managing the deterioration in prosperity in ways that maximise efficiency and minimise division.

Any government which understands what prosperity is and where it is going will also reach some obvious but important conclusions.

The first is that prosperity issues have risen higher on the political agenda, and will go on doing so, pushing other issues down the scale of importance.

The second conclusion, which carries with it what is probably the single most obvious policy implication, is that redistribution is becoming an ever more important issue. There are two very good reasons for this hardening in sentiment.

For starters, popular tolerance of inequality is linked to trends in prosperity – resentment at “the rich” is muted when most people are themselves getting better off, but this tolerance very soon evaporates when subjected to the solvent of generalised hardship.

Additionally, the popular narrative of the years since 2008 portrays “austerity” as the price paid by the many for the rescue of the few. The main reason why this narrative is so compelling is that, fundamentally, it is true.

The need for redistribution is reinforced by realistic appraisal of the fiscal outlook. Anyone who is aware of deteriorating prosperity has to be aware that this has adverse implications for forward revenues. By definition, only prosperity can be taxed, because taxing incomes below the level of prosperity simply drives people into hardships whose alleviation increases public expenditures.

In France, for example, aggregate national prosperity is no higher now (at €1.76tn) than it was in 2008, but taxation has increased by 17% over that decade. Looking ahead, the continuing erosion of prosperity implies that rates of taxation on the average person will need to fall, unless the authorities wish further to tighten the pressure on the typical taxpayer.

Even the inescapable increase in the taxation of the very wealthiest isn’t going to change a scenario that dictates lower taxes, and correspondingly lower public expenditures, as prosperity erodes.

A new centre of gravity?

The adverse outlook for government revenues is one reason why the political Left cannot expect power to fall into its hands simply as a natural consequence of the crumbling of failed centre-Right incumbencies. Those on the Left keen to refresh their appeal by cleansing their parties of the residues of past compromises have logic on their side, but will depart from logic if they offer agendas based on ever higher levels of public expenditures.

With prosperity – and, with it, the tax base – shrinking, promising anything that looks like “tax and spend” has become a recipe for policy failure and voter disillusionment. This said, so profound has been the failure of the centre-Right ascendancy that opportunities necessarily exist for anyone on the Left who is able to recast his or her agenda on the basis of economic reality.

Tactically, the best way forward for the Left is to shift the debate on equality back to the material, restoring the primacy of the Left’s traditional concentration on the differences and inequities between rich and poor.

On economic as well as fiscal and social issues, we ought to see the start of a “research arms race”, as parties compete to be the first to absorb, and profit from, the recognition of economic realities that are no longer (if they ever truly were) identified by outdated methods of economic interpretation.

Historically, the promotion of ideological extremes has always been a costly luxury, so is likely to fall victim to processes that are making luxuries progressively less affordable. Voters can be expected to turn away from the extremes of pro- public- or private-sector promotion, seeing neither as a solution to their problems.

This, it is to be hoped, can lead to a renaissance in the idea of the mixed economy, which seeks to get the best out of private and public provision, without pandering to the excesses of either. Restoration of this balance, from the position where we are now, means rolling back much of the privatization and outsourcing undertaken, often recklessly, over the last three decades.

Both the private and the public sectors will need to undergo extensive reforms if governments are to craft effective agendas for using the mixed economy to mitigate the worst effects of deteriorating prosperity.

In the private sector, governments could do a lot worse than study Adam Smith, paying particular attention to the explicit priority placed by him on promoting competition and tackling excessive market concentration, and recognizing, too, the importance both of ethics and of effective regulation, both of which are implicit in his recognition that markets will not stay free or fair if left to their own devices.

For the public sector, both generally and at the level of detail, there will need to be a renewed emphasis on the setting of priorities. With resource limitations set not just to continue but to intensify, health systems, for example, will need to become a lot clearer on which services they can, and cannot, afford to fund.

Starting from here

Though this discussion can be no more than a primer for discussion, there are two points on which we can usefully conclude.

First, a useful opening step in the crafting of new politics would be the introduction of “clean hands” principles, designed to prove that government isn’t, as it can so often appear, something conducted “by the rich, for the rich”.

Second, it would be helpful if governments rolled back their inclinations towards macho posturing and intimidation.

A “clean hands” initiative wouldn’t mean that elected representatives would be paid less than currently they are. There is an essential public interest in attracting able and ambitious people into government service, so there’s nothing to be said for hair-shirt commitments to penury. In most European countries, politicians are not overpaid, and it’s arguable that their salaries ought, in some cases at least, to be higher.

There is, though, a real problem, albeit one that is easily remedied. This problem lies in the perception that politics has become a “road to riches”, with policymakers retiring into the wealth bestowed on them by the corporate sponsors of ‘consultancies’ and “the lecture circuit”. This necessarily creates suspicion that rewards are being conferred for services rendered, a suspicion that is corrosive of public trust, even where it isn’t actually true.

The easy fix for this is to cap the earnings of former ministers and administrators at levels which are generous, but are well short of riches. The formula suggested here in a previous discussion would impose an annual income limit at 10x GDP per capita, which is about £315,000 in Britain, with not-dissimilar figures applying in other countries. It seems reasonable to conclude that anyone who thinks that £300,000, or its equivalent, “isn’t enough” is likely to have gone into politics for the wrong reasons.

Where treatment of the “ordinary” person is concerned, there ought, in the future, be no room for the intimidatory practices which have become ever more popular with governments whose real authority has been weakened by failure.

One illustrative example is the system by which council tax (local taxation) arrears are collected in Britain. At present, the typical homeowner pays £1,671 annually, in ten monthly instalments. If someone misses a payment, however, he or she is then required to pay the entire annual amount almost immediately, compounded by court costs of £84 and bailiff fees of £310. Quite apart from the inappropriateness of involving the courts or employing bailiffs, it’s hard to see how somebody struggling to pay £167 is supposed to find £2,067.

This same kind of intimidation occurs when people are penalized for staying a few minutes over a parking permit, or for exceeding a speed limit by a fractional extent. Here, part of the problem arises from providing financial incentives to those enforcing regulations, a practice that should be abandoned by any government aware of the need to start narrowing the chasm between governing and governed.

We cannot escape the conclusion that the task of government, always a thankless one even when confined to sharing out the benefits of growth, is going to become very difficult indeed as prosperity continues to deteriorate.

There might, though, be positives to be found in a process which ditches ideological extremes, uses the mixed economy as the basis for the equitable mitigation of decline, and seeks to rebuild relationships between discredited governments and frustrated citizens.