ENTERPRISE IN A DE-GROWING, DE-LAYERING ECONOMY

We start the 2020s with the political, economic, commercial and financial ‘high command’ quite remarkably detached from the economic and financial reality that should inform a huge variety of policies and decisions.

This reality is that the relentless tightening of the energy equation has already started putting prior growth in prosperity into reverse. No amount of financial gimmickry can much longer disguise, still less overcome, this fundamental trend, but efforts at denial continue to add enormously to financial risk.

This transition into uncharted economic waters has huge implications for every category of activity and every type of player. Just one example is government, for which the reversal of prior growth in prosperity means affording less, doing less, and expecting less of taxpayers (with the obvious corollary that the public should expect less of government).

Governments, though, do at least have alternatives. ‘Doing less’ could also mean ‘doing less better’ – and, if the public cannot be offered ever-greater prosperity, there are other ways in which the lot of the ‘ordinary’ person can be improved.

At first sight, no such alternatives seem to exist for business. The whole point of being in business, it can be easy to assume, is the achievement of growth. Whether it’s bigger sales, bigger profits, a higher profile, a growing market value or higher dividends for stockholders, every business objective seems tied to the pursuit of expansion.

None of this, in the aggregate at least, seems compatible with an economy in which the prosperity of customers is shrinking.

In reality, though, both de-growth and de-layering offer opportunities as well as challenges. The trick is to know which is which.

For those of us not involved in business, the critical interest here is that, driven as they are by competition, businesses are likely to be quicker than other sectors to recognise and act upon the implications of the post-growth economy.

Getting to business

How, then, are businesses likely to position themselves for the onset of de-growth? The answer begins with the recognition of two realities.

The first of these is that prosperity is deteriorating, and that there is no ‘fix’ for this situation.

The second is that ‘price isn’t value’.

As regular readers will know, prosperity in most of the Western advanced economies (AEs) has been in decline for more than a decade, and a similar climacteric is nearing for the emerging market (EM) nations.

This fundamental trend is, as yet, unrecognised, whether by ‘conventional’ economic interpretations, governments, businesses or capital markets. It is already felt, though, if not necessarily yet comprehended, by millions of ordinary people.

‘Conventional’ economics, with its fixation on the financial, fails to recognise the deterioration of prosperity because it overlooks the critical fact that all economic activity is driven by energy. There is no product or service of any economic utility which can be supplied without it. Money and credit are functions of energy because, being an artefact wholly lacking in intrinsic worth, money commands value only as a ‘claim’ on goods and services – all of which, of course, are themselves products of the use of energy.

The complicating factor in the prosperity equation is that, whenever energy is accessed for our use, some of that energy is always consumed in the access process. This consumed proportion is known here as ECoE (the Energy Cost of Energy), a concept related to previously-defined concepts such as net energy and EROI.

Critically, what remains after the deduction of ECoE is surplus energy. The aggregate of available energy thus divides into two components. One of these is ECoE, and the other is surplus energy, which drives all economic activity other than the supply of energy itself.

This makes surplus energy coterminous with prosperity.

The relentless (and unstoppable) rise in ECoEs has now squeezed aggregate prosperity to the point where the average person is getting poorer. There is nothing that can be ‘done about’ this, so the necessity now is to adapt.

SEEDS – the Surplus Energy Economics Data System – has been built and refined to model the economy on this basis. Its identification of deteriorating prosperity accords with numerous ‘on the ground’ observations, whether in economics, finance, politics or society.

But general recognition of this interpretation has yet to occur, and, in its absence, the economic history of recent years has been shaped by efforts to use the financial system to deny (since we cannot reverse) this process. The main by-product of this exercise in denial has been excessively elevated risk.

Conclusions come later, but an important point to be noted from the outset is that, as the economy gets less prosperous, it will also get less complex, resulting in the phenomenon of ‘de-layering’. An understanding of this and related processes will be critical to success in an economic and business landscape entering unprecedented change.

The reality of deteriorating prosperity

A necessary precondition for the formulation of effective responses is the recognition of where we really are, and there are two observations with which this needs to start.

The first is the ending and reversal of meaningful “growth” in prosperity. Any businessman or -woman who believes that economic “growth” is continuing ‘as usual’, or can somehow be restored, needs to reframe his or her interpretation radically. Indeed, it’s been well over a decade (and, in many instances, nearer two decades) since the advanced economies of the West last achieved genuine growth in economic prosperity.

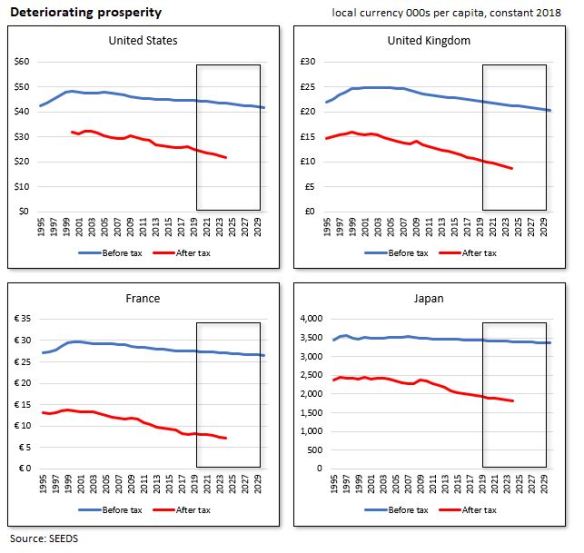

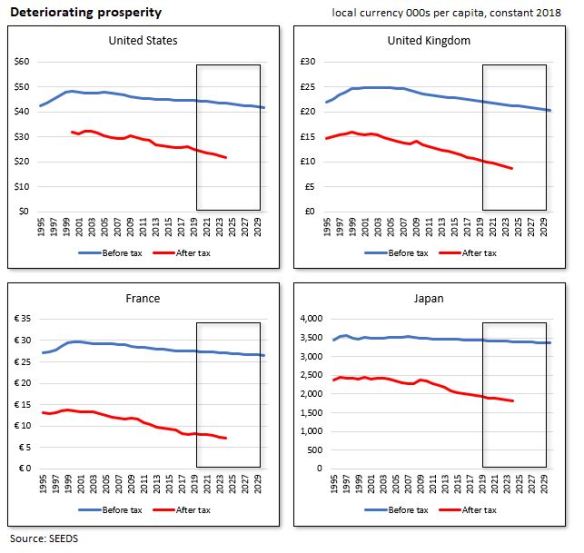

For illustration, the deterioration in average personal prosperity in four Western countries, both before and after tax, is set out in the following charts. Examination of the trend in post-tax (“discretionary”) prosperity in France, in particular, does much to explain widespread popular discontent.

Worse still, from a business perspective, a similar downturn is now starting in the hitherto fast-growing EM economies, including China, India and Brazil.

To be sure, the authorities have done a superficially plausible job of hiding the reality of falling prosperity, first by pumping cheap credit into the system and, latterly, by doubling down on this and turning the real cost of money negative. The only substantive products of these exercises in credit and monetary adventurism, though, have been enormous increases in financial exposure.

The cracks are now beginning to show, and in ways that should be particularly noticeable to business leaders.

Sales of a broadening number of product categories, from cars and smartphones to chips and components, have turned down. Debt continues to soar (which is hardly surprising in a situation in which people are being paid to borrow), and questions are starting to be asked about credit ratings, debt servicing capability and the possible onset of ‘credit exhaustion’ (the point at which borrowers no longer take on any more credit, however cheap it may be).

Whole sectors (such as retailing and air travel) are already being traumatised. Returns on invested capital have collapsed, and this has had knock-on effects in many areas, but nowhere more so than in the adequacy of pension provision (where the World Economic Forum has warned of a “global pensions timebomb”). Even before this pensions reality strikes home to them, ordinary people are becoming increasingly discontented, whether this is shown on the streets of Paris and other cities, or in the elections whose outcomes have included Donald Trump, “Brexit” and a rising tide of “populism” (for which the preferred term here is insurgency) and nationalism.

There are, of course, those who contend that falling sales of cars and chips ‘don’t matter very much’, because we can continue to sell each other services which, even where they are of debateable value, can still be monetised, so will continue to generate revenues. These assurances tend to come from the same schools of thought which previously told us that debt, too, ‘doesn’t matter very much”.

This wishful thinking, arguably most acute in the ‘tech’ sector, ignores the fact that, as the average consumer gets poorer, he or she is going to be become more adept, or at least more selective and demanding, in the ranking of value. In a sense, the failure to recognise this trend repeats some of the misconceptions of the dot-com bubble – and the answer is that you can only be happy about ‘virtual’ and ‘intangible’ products and sales if you’re equally relaxed about earning only virtual and intangible profits. But business is, or should be, about cash generation – nobody ever bought lunch out of notional profits.

Let’s put this in stark terms. If someone is in the business of selling holidays, he or she makes money when people actually travel to the facility, and pay to use its services. They could, of course, sell them computer-generated virtual tours of the facility as a sort of proxy-residency – but does anyone really think that that’s a substitute for the revenue that is earned when they actually visit in person?

Another way to look at this is that businesses are likely to become increasingly wary of middle-men and ‘agencies’. This reflects de-layering, an issue to which we shall return later. But the general proposition is that, in de-growth, businesses will prosper best when they capture as much of the value-chain as possible, ensuring that ‘value’ predominates over ‘chain’.

Ancillary services, and ancillary layers, are set to be refined out, and businesses are likely to become increasingly wary of others trying to monetise parts of their chain.

Understanding value

The second reality requiring recognition is that the prices of capital assets, including stocks, bonds and property, have risen to levels that are both (a) wholly unrelated to fundamental value, and (b) incapable of being sustained, under present or conceivable economic conditions.

Statements like “the Fed has your back” are illustrative of quite how irrational this situation has become. The idea that inflated asset prices can be supported indefinitely by the perpetual injection of newly-created liquidity is puerile beyond any customary definition of that word.

We may not know how long asset prices can continue to defy economic gravity, or how the eventual reset will take place, but the definition of ‘unsustainable’ is ‘cannot be sustained’.

A general point needing to be made is that is called “value” by Wall Street and its overseas equivalents is of little relevance to what the word should mean in business. The interests of business and of the capital markets are by no means coterminous, since the objectives of each are quite different. The astute business leader might listen to the opinions of those in the financial markets, but acts only on his or her own informed conclusions.

From a business perspective, the value of an asset is the current equivalent of its future earning capability. No apology is made to those who already understand this universal truism, because, though fundamental, it is all too often overlooked. This principle can be best be illustrated by looking at a simple example such as a toll bridge.

To the owner (or potential acquirer) of a toll bridge, various future factors are known, though with varying degrees of confidence. He or she should know, at high levels of confidence, appropriate rates of depreciation and costs of maintenance. He has an informed opinion, albeit at a somewhat lesser level of confidence, about what the future toll charges and numbers of users are likely to be.

This information enables him to project into the future annual levels of revenue and cost. He can, moreover, divide the cost component into cash and non-cash components, the latter including depreciation and amortisation. From this, he can create a numerical forward stream of projected cash flows and earnings.

The question which then arises is that of what value today can be ascribed most appropriately to the income stream to be realised in the future.

This process requires risk-weighting. Costs and taxes may turn out to be higher or lower than the central case assumptions, and the same is true of revenue projections. Customer numbers and unit revenues may be influenced by factors outside either the control of the owner or of his ability to anticipate. Degrees of variability can and should be factored in to the calculation of appropriate risk.

What happens now is that a compounding discount factor is created by combining risk, inflation, cost of capital and the time-value of money. Application of this factor turns future projections into numbers for discounted cash flow (DCF) as a net present value (NPV).

There is nothing at all novel about DCF-NPV calculation, and it is used routinely by those valuing individual commercial assets. It is, incidentally, far more reliable than ROI (return on investment) or ROC (return on capital) methodologies, let alone IRR (internal rate of return).

Importantly, though, this valuation procedure is applicable to all business ventures. The process becomes increasingly complex as we move from the simple asset to the diversified, multi-sector business, and increasingly conjectural where rising levels of uncertainty (over, for instance, future rates of growth) are involved.

But the principle – that the worth of a business asset is coterminous with what it will earn in the future – remains central.

The nearest that capital markets tend to get to this is to price a company on the basis of its future earnings, which is where the P/E ratio (and its various derivatives) fit into the process. A more demanding (but more useful) approach substitutes cash flow for earnings, and generates the P/CF ratio. P/FCF (price/free cash flow) is a still better approach, though all cash flow-based calculations need to ensure that a tight definition and a robust methodology are involved.

Where P/E ratios are concerned, both growth potential and risk should be (though often aren’t) reflected in multiples. When one company is priced at, say, 10x earnings whilst another is priced at 20x, it’s likely that the latter is valued more aggressively than the former because growth expectations are higher (though it is also possible that the lower-rated company is considered to be riskier).

Much of the foregoing will be well-known to any competent business leader or analyst. It is referenced here for two reasons – first, because it produces valuations which typically bear little or no resemblance to today’s hugely inflated financial market pricing of assets and, second, because an understanding of fundamental value needs to be placed at the centre of any informed response to the onset of de-growth.

Markets are driven by many factors beyond the trinity of ‘fear, greed and [sometimes] value’. Supplementary, non-fundamental market factors, whether or not they are of meaningful relevance to investors and market professionals, should not exert undue influence on the decisions made by business leaders. “What will my share price be in a year from now?” may be an interesting subject for speculation, but should play little or no part in planning.

This point is stressed here because deteriorating prosperity will invalidate almost all market assumptions. This deterioration is an extraneous factor not yet known to the market. It destroys the credibility of the ‘aggregate growth’ assumption which informs the pricing both of individual companies and of sectors. It impacts customer behaviour, and customer priorities, in ways that markets could not anticipate, even if they were aware of the generalised concept of de-growth.

This is why business strategy needs to incorporate a concept which may be called ‘de-complexifying’ or, more succinctly, de-layering.

The critical understanding – the de-layering driver

It’s useful at this point to reflect on the way in which our economic history can be defined in surplus energy terms.

Our hunter-gatherer ancestors had no surplus energy, because all of the energy that they derived from nutrition was expended in the obtaining of food. Agriculture, because it enabled twenty individuals or families to be fed from the labour of nineteen, created the first recognizable economy and society because of the surplus energy which enabled the twentieth person to carry out non-subsistence tasks. This economy was rudimentary, reflecting the fact that the energy surplus was a slender one. Latterly, accessing the vast energy contained in fossil fuels leveraged the surplus enormously, which meant that only a very small proportion of the population needed now to be engaged in subsistence activities, with the vast majority now doing other things.

This process made the economy very much larger, of course, but it’s more important, especially from a business perspective, to note that it also made it very much more complex. Where once, for example, we had only farmers and grocers, with very few layers in between, food supply has since become vastly more diverse, involving an almost bewildering array of trades and specialisations. The linkage between expansion and complexity holds true of all sectors.

The most pertinent connection to be made here is that, just as prior growth in prosperity has driven growth in complexity, the deterioration in prosperity is going to have the opposite effect, initiating a trend towards a reduction in complexity. One term for this is ‘simplification of the supply chain’. Another, with applications far beyond commerce, is de-layering.

This has two stark and immediate implications for businesses.

First, a business which can front-run de-layering, simplifying its operations before others do so, can gain a significant competitive advantage.

Second, if a business is one that might get de-layered, it would be a good idea to get into a different business.

First awareness

In this discussion we have established three critical understandings:

– Prosperity is deteriorating, for reasons which mainstream interpretation has yet either to recognise or to understand.

– Attempts to ‘fix’ this physical reality by means of financial gimmickry have resulted only in increases in risk, many of them associated with the over-pricing of assets.

– As prosperity decreases, the economy will de-complexify.

These points describe a situation whose reality is as yet largely unknown, but one reason for selecting business (rather than, say, government, the public sector or finance) for this first examination of the sector implications of deteriorating prosperity is that businesses are likely to discover this new reality more quickly than other organisations.

Whilst by no means free from the assumptions, conventions, ‘received wisdoms’ and internal group interests that operate elsewhere, businesses are driven by competition – and this means that, should a small number of enterprises discover and act upon the implications of de-growth, de-layering and disproportionate risk, others are likely to follow.

We cannot, of course, discuss here the many practical steps which are likely to follow from recognition of the new realities and, in some cases, it might be inappropriate to do so.

It seems obvious, though, that a business which becomes familiar with the situation as it is described here will seek to take advantage of inappropriately elevated asset prices, and to test its value-chain and its operations in the light of future de-layering. Ultimately, the aim is likely to be to front-run both de-layering and revaluation. Moreover, awareness of those countries in which prosperity deterioration is at its most acute is likely to sharpen the focus of multi-regional companies.