PLANNING FOR A CONTRACTING ECONOMY

I still have vivid recollections of my first experience of driving in a big city – in my case, London – where the volume, speed and aggression of traffic was outside all my prior rural and small-town motoring experience. The collective attitude seemed to be: “I may not know where I’m going – but I’ll get there before you do!”

Financial markets seem to have adopted a similarly frenetic mentality, characterised by a combination of breathtaking speed and a complete lack of direction.

Just weeks ago, in the full flood of AI euphoria, the NASDAQ index hit an all-time high. It has since dropped rapidly, unwinding all gains made since September 2021. The stock price of Nvidia, poster-child for the AI afficionados, has fallen by 20% in less than a month.

My attitude to this directionless froth and frenzy is to reflect on The Worthington Factor, the thought being that Don’t put your daughter into tech, Mrs Worthington would be an appropriate soundtrack for our times. Equally, There are bad times just around the corner is an apt commentary on unfolding prospects in many economies and, for once, I will particularize, saying that Mrs Worthington would be especially unwise if she invested her daughter’s future in Britain or Japan.

Many of us never believed that AI was going to be world-changing anyway, so this latest handbrake-turn in market sentiment is, perhaps, of little material significance.

What’s far more important right now is that the transition to renewable energy is decelerating markedly, whilst even the BBC has noticed “cooling interest in electric vehicles”.

In big-picture terms, then, whilst investor gains or losses on the latest technological fad might not matter very much, the same can’t be said of the unfolding failure of the consensus narrative of ‘sustainable growth built on ultra-cheap renewables and limitless advances in technology’.

In stark contrast to market drama, the consensus line on global economic conditions has become almost soporific. Growth is continuing, we’re told, though some observers are starting to concede that long-term growth trends have been softening.

Likewise, we can rest assured of an economic soft-landing, whilst financial risk, though elevated, remains manageable. Inflation, although proving surprisingly sticky, is being brought back under control, and central banks may be able to relax their monetary policies in the not-too-distant future.

In search of answers

Looking beyond rollercoaster markets and the sleep-inducingly laid-back economic consensus, many of us – whether as consumers, voters, employees, employers, entrepreneurs or investors – want to know what’s going to happen next, and we can’t obtain this information from market or consensus sources.

The aim here is to try to provide some answers.

The conclusion is that, at this point, the wise person should be putting little or no faith in promises of “growth”, especially where these promises are based on energy transition, the advance of technology or the wisdom of decision-makers in government, business or finance.

Beyond a general scepticism about the promises made by political leaders, we need to recognise that some national economies are in very, very big trouble.

I’ve been busy putting the latest raft of economic data into SEEDS, but the projections supplied by the system are very largely unchanged. My broad conclusion is that decision-makers either don’t know, or choose not to discuss, where the economy and the financial system are really going.

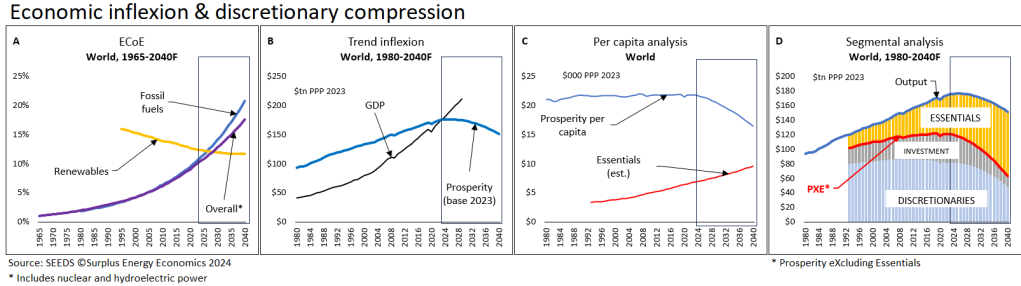

In economic terms, material prosperity is at, or very near, the point at which prior growth inflects into contraction. Meanwhile, the real costs of necessities are continuing to rise.

The result is leveraged compression of the affordability of discretionary (non-essential) products and services. As well as keeping her daughter out of “tech”, a modern Mrs Worthington would be well advised to steer clear of sectors supplying things which consumers may want, but don’t need. Obvious examples include leisure, travel, hospitality, media and real estate.

Financially, decision-makers are sitting in the cab of a runaway railway locomotive, pulling one lever after another in a frenzied – and futile – effort to stave off an impending wreck.

It might help to put some numbers on this. With everything stated at constant 2023 values, reported global GDP has expanded by $88 trillion over the past twenty years. But this has been accompanied – indeed, made possible – by a $290tn increase in debt, the latter accounting for only half of an estimated $580tn escalation in broader liabilities over the same period.

SEEDS headline numbers put this into context. Since 2003, and in stark contrast to the reported doubling of GDP since then, global aggregate prosperity has increased by only 28%. Because the world’s population rose by 26% between 2003 and 2023, the average person was less than 2% more prosperous last year than he or she was twenty years ago. Against that, his or her share of total debt far more than doubled – it rose by 140% – between those years.

The projections provided by SEEDS don’t, at first sight, look particularly frightening. In comparison with 2023, aggregate prosperity is forecast only fractionally lower by 2030, though 14% reduced by 2040. The world’s average person is set to be 7% poorer by 2030, and 25% less prosperous by 2040. This is a far cry from the imminent economic “collapse” predicted by some.

The devil, though, is in the detail. Whilst the world’s average person may be “only” 7% poorer by 2030, his or her cost of essentials is projected to rise by 14% in real terms over that period. This means that per capita PXE – Prosperity eXcluding Essentials – will fall by 17% in the coming seven years, and will have more than halved (-54%) by 2040.

This why Mrs Worthington’s daughter needs to steer well clear of discretionaries, and plan a career in a sector which supplies necessities to consumers.

Fig. 1

There is, as you might expect, a nasty sting in the tale of discretionary contraction.

As well as ceasing to be able to afford costly holidays, a new car or entertainment subscriptions, and in addition being unable to respond to the allure of the advertised, the average person is going to find it increasingly hard to ‘keep up the payments’ on all of the mortgages, secured and unsecured loans and broader financial commitments taken on in the years of reckless credit expansion.

This takes us, necessarily, into the question of risk. The consensus line about financial risk being manageable is based on the mistaken assumption that credit carrying capacity will expand even as the quantum of obligations continues to rise. This, though, isn’t going to happen.

We’ve reached a point at which event risk – vulnerabilities to wars, pandemics and localised crises – is recognised, whilst process and systemic risk are not.

By process risk is meant a deterioration in the economy as a system for the supply of material products and services to society. Systemic risk references the consequences of a continuing worsening in the disequilibrium between the “real” and the “financial” economies.

It’s time for us to get into some economic fundamentals.

Looking backwards, looking forwards

Having started my career as an oil and gas analyst, it was never much of a stretch to work out that the economy itself is an energy system – there was probably no point at which I wasn’t fully aware of this.

Writing investment strategy research in the heat of the 2008-09 global financial crisis, however, led to one inescapable conclusion, which was that the financial system had become massively out-of-kilter with the underlying economy itself – there was, and remains, no other way of explaining the fundamental causation of the GFC.

This led to the conclusion that the economy cannot be interpreted in terms of money alone, but requires recognition of the concept of two economies – a “real economy” of material products and services, and a parallel “financial economy” of money, transactions and credit.

I put these ideas forward in a series of reports – including Perfect Storm – authored as global head of research at Tullett Prebon, one of the world’s biggest inter-dealer brokers, and developed them in the book Life After Growth, published in 2013.

Whilst writing the latter, I became uncomfortably aware of an inability to model and project the material “real” economy, both as the driver of prosperity and as the underlying basis of the set of financial processes lazily, and mistakenly, referred to as “the economy”.

To cut these recollections short, it took five years to complete the calculation of material prosperity, and another five to explore the ramifications of the two economies concept whilst refining and developing the SEEDS model.

Fortuitously, completion of this project occurred just as unmistakable evidence began to emerge of the ending of the precursor zone, and the onset of the inflexion of the economy from growth into contraction.

The Surplus Energy Economics approach is based on three principles, each of which seems incontrovertible. The first is that of prosperity as a material concept, provided by the use of energy to convert natural resources into products and services.

Since the supply and use of energy requires a material infrastructure – and nothing material can be created, operated, maintained or replaced without the use of energy – it follows that, whenever energy is accessed for our use, some of that energy is always consumed in the access process, and is unavailable for any other economic purpose.

This “consumed in access” component is known in SEE as the Energy Cost of Energy, adding the principle of ECoE to the principle of the economy as an energy system.

The third basic principle is that of money as claim. This recognises that, since money has no intrinsic worth – we can’t eat money, or power our cars with it – it commands value only as an exercisable claim on those material products and services for which it can be exchanged.

When, along these lines, we compare the material economy with its monetary counterpart, it becomes apparent that the history and future of the material and monetary economies needs to be recalibrated in terms of two dynamics. One of these is the supply, value and cost of energy. The second is the relationship between the energy and financial economic systems.

ECoE is critical in these interconnected dynamics. If we have to consume, say, 90 energy units to put 100 energy units to use, we have a low prosperity system, indeed an economy comparable to the agrarian societies that preceded industrialization.

If, conversely, we can consume only 1 or 2 energy units in harnessing 100, the effect on prosperity is transformational.

This is the nature of the economic transformation which, known to historians as the Industrial Revolution, followed from the harnessing of fossil fuel energy in the late 1700s.

Our predicament now is, in its fundamentals, simply stated. The trend ECoEs of fossil fuels are rising inexorably, as a consequence of, quite naturally, using lowest-cost resources of oil, natural gas and coal first, and leaving costlier alternatives for later.

Contrary to widespread assumption, renewable energy sources, such as wind and solar power, cannot take us back to low ECoEs enjoyed in the heyday of carbon fuels. The material characteristics of renewables make this impossible, and technology – again contrary to widespread supposition – can’t repeal the laws of thermodynamics in order to make it possible.

It was never likely that we would choose to address environmental and ecological hazard by voluntarily relinquishing our fixation with “growth”. One doesn’t need to be unduly cynical to think that sustainability alone could never have been sold to the public as a choice preferable to consumerism. This, perhaps, is why the pursuit of environmental responsibility has been presented to the public as a promise of “sustainable growth”.

As the economy inflects from growth into contraction, two trends, at least, are clear. The first is that we’re going to have to prioritise needs over wants. The second is that we’ll have to redesign a financial system built on the false predicate of infinite, exponential economic expansion on a finite planet.

Listening to the song, it’s hard not to feel sorry for young Miss or Ms Worthington, for whom “the width of her seat/would surely defeat/her chances of success” treading the boards, whilst “an ingénue role/would emphasise her squint”.

But at least her modern-day equivalents can choose not to make their prospects worse by ignoring the hard realities of an inflecting economy and a dangerously over-stressed financial system.