REALITY AND THE ROUTE TO NET ZERO

Monthly Archives: May 2021

#199. An American nightmare

ENERGY, “GROWTH” AND THE LIABILITY VORTEX

“Time moves on”, at least in politics, and it should now be possible for us to examine the American economic situation without being drawn into recent controversies.

In any case, our primary interests here are the economy, finance and the environment, understood as functions of energy, and these are issues to which political debate is only indirectly connected. We cannot know whether the economic policies now being followed in the United States would have been different if Mr Biden hadn’t replaced Mr Trump in the Oval Office, and what we ‘cannot know’ is far less important than what we do.

If you’re new to this site, all you really need to know about the techniques used here is that the economy is understood and modelled, not as a financial construct, but as an energy system. Literally everything that constitutes economic output is a function of the use of energy. Whenever energy is accessed for our use, some of that energy is always consumed in the access process, and this Energy Cost of Energy (ECoE) governs the dynamic which converts energy into prosperity.

Money – which, after all, is simply a human artefact – has no intrinsic worth, and commands value only as a ‘claim’ on the output of the real economy governed by the energy dynamic. Energy, moreover, is the interface between economic prosperity and the environment.

American dysfunction

Even without getting into the energy fundamentals, a string of dysfunctionalities in the American economic situation should be visible to anyone prepared to look. These are best considered, not within the current disturbances created by the coronavirus pandemic, but on the basis of trends that have been in place for a much longer period.

Most obviously, the aggregate of American debt – combining the government, household and private non-financial corporate (PNFC) sectors – increased in real terms by $28 trillion (104%) between 1999 and 2019, a period in which recorded GDP grew by only $7.4tn.

One way to look at this is that each dollar of reported “growth” was accompanied by $3.75 of net new debt. Another is that, over twenty years in which growth averaged 2.0%, annual borrowing averaged 7.5% of GDP.

To be sure, some of these ratios have been even worse in other countries, but schadenfreude has very little value in economics. Moreover, debt is by no means the only (or even the largest) form of forward obligation that has been pushed into the American economy in order to create the simulacrum of “growth”.

Other metrics back up this interpretation. Within total growth (of $7.4tn) in reported GDP between 1999 and 2019, only $160bn (2.2%) came from manufacturing. A vastly larger (25.3%) contribution to growth came from the FIRE (finance, insurance and real estate) sectors.

These and other services are important but – unlike sectors such as manufacturing, construction and the extractive industries – they are residuals, priced on a local (‘soft’) basis rather than on ‘hard’ international markets.

To over-simplify only slightly, many services act as conduits for the financial ‘activity’ created by the injection of credit and liquidity into the system.

The real picture – of credit and energy

The SEEDS model endeavours to strip out these distorting effects, and indicates that underlying or ‘clean’ economic output (C-GDP) in the United States grew at an average rate of only 0.7% (rather than 2.0%) between 1999 and 2019.

In essence, reported GDP has been inflated artificially by the insertion of a credit wedge which is the corollary of the ‘wedge’ inserted between debt and GDP (see fig. 1).

Fig. 1

This much should be obvious even to those shackled to quaint, ‘conventional’ economic metrics which – bizarre as it may seem – ignore energy, and insist on wholly financial interpretation of the economy. To trace these anomalies to their cause, though, we need to look at the energy dynamic and, in particular, at the ECoE equation which governs the supply, cost and economic value of energy.

Globally, trend ECoEs are rising rapidly, driven by the depletion effect as it affects petroleum, natural gas and coal. The ECoEs of renewables (REs) such as wind and solar power are falling, but it would be foolhardy to assume that this can push overall ECoEs back downwards at all, let alone to the pre-1990s levels at which real growth in prosperity remained possible. Apart from anything else, RE expansion requires vast material inputs which are themselves a cost function of legacy energy from fossil fuels.

ECoEs equate to economic output which, because it has to be expended on energy supply, is not available for any of those other economic uses which constitute prosperity. This is why SEEDS draws a distinction between underlying economic output (C-GDP) and prosperity.

On an average per capita basis, American prosperity topped out back in 2000 (at $49,400 at constant 2020 values), when national trend ECoE was 4.5%. By 2019, with ECoE now at 9.0%, the average American was 6.6% ($3,275) poorer than he or she had been in 2000. Of course, his or her share of aggregate debt increased (by $68,500, or 71%) over that same period (see figs. 2 and 3).

Again, there are other countries where these numbers are worse. Again too, though, what’s happening in other countries is of very little relevance to a person whose indebtedness is rising whilst his or her prosperity is subject to relentless erosion.

Fig. 2

The fading dream

Just as prosperity per person has been deteriorating, the cost of essentials has been rising. To be clear about this, the calibration of “essentials” (defined as the sum of household necessities and public services) within the SEEDS economic model remains at the development stage, but the results can at least be treated as indicative.

As we can see in the left-hand chart in fig. 3, discretionary prosperity has been subjected to relentless compression between deteriorating top-line prosperity per capita and the rising cost of essentials, a cost which, in turn, is significantly linked to upwards trends in ECoE.

Discretionary consumption has continued to increase – thus far, anyway – but only as a function of rising indebtedness in each of the public, household and PNFC (corporate) sectors. Even these numbers are based on per capita averages, so necessarily disguise a worse situation at the median income level.

Fig. 3

The liability vortex

Back at the macroeconomic level, America is, very clearly, being sucked into a liability vortex.

Even before the coronavirus crisis, debt stood at 360% of prosperity, up sharply over an extended period, whilst the broader and more important category of “financial assets” – essentially the liabilities of the government, household and PNFC sectors – had risen to 725% of prosperity (fig. 4).

Fig. 4

Like anyone else, Americans can derive false comfort by measuring these liability aggregates, not against prosperity but against GDP, if they’re happy to buy the fallacy that GDP isn’t inflated artificially by financial liability expansion.

Another, almost persuasive source of false comfort can be drawn from the inflated “values” of assets such as stocks and property. The realities here, though, are that the only people who could ever buy properties owned by Americans are other Americans, meaning that the supposed aggregate “value” of the national housing stock cannot ever be monetized. The same, albeit within an international rather than a purely national frame of reference, applies to the aggregate “values” of stocks and bonds.

More important still, asset prices are an inverse function of the cost of money, and would fall sharply if it ever became necessary to raise interest rates.

Debate rages in America, as elsewhere, about whether inflation is rising at all, and whether, if it is rising, this is a purely ‘transitory’ effect of contra-crisis liquidity injection. An additional complication here is that inflationary measurement excludes rises in asset prices and may, even within its consumer price confines, be an understatement of what’s really happening. The SEEDS-based development project RRCI – the Realised Rate of Comprehensive Inflation – puts indicative American inflation at 5.2% in 2020, rising to a projected 6.6% this year.

Cutting to the chase

This debate over the reality and the rate of inflation, though, risks missing the point, which is that the in-place dynamic between liabilities and economic output makes either inflation, and/or a cascade of asset price slumps and defaults, an inescapable, hard-wired part of America’s economic near future.

Even before Covid-19, each dollar of reported “growth” was being bought with $3.75 of net new borrowing, plus an incremental $3.80 of broader financial obligations. Even these numbers exclude the informal (but very important) issue of the future affordability of pensions.

Crisis responses under the Biden administration – responses which might not have been very different under Mr Trump – are accelerating the approach of the point at which, America either has to submit to hyperinflation or to tighten monetary policy in ways that invite the corrective deflation of plunging asset markets and cascading defaults.

The baffling thing about this is that you don’t need an understanding of the energy dynamic, or access to SEEDS, to identify unsustainable trends in relationships between liabilities, the quantity of money, the dramatic over-inflation of asset markets and a faltering underlying economy.

Confirmative anomalies are on every hand, none of them more visible than the sheer absurdities of paying people to borrow, and trying to run a capitalist economy without real returns on capital. Meanwhile, slightly less dramatic anomalies – such as the investor appetite for loss-making companies, the “cash burn” metric and the use of debt to destroy shock-absorbing corporate equity – have now become accepted as routine.

Obvious though all of this surely is, denial seems to reign supreme. Mr Trump – and his equation linking the Dow to national well-being – may have gone, but government and the Fed still cling to some very bizarre mantras.

One of these is that stock markets must never fall, and that investors mustn’t ever lose money. Another is that nobody must ever default, and that bankruptcies destroy economic capacity (the reality, of course, is that bankruptcy doesn’t destroy assets, just transfers their ownership from stockholders to creditors).

Businesses, meanwhile, seem almost wilfully blind to the connection between consumer discretionary spending, escalating credit and the monetization of debt.

On the traditional basis that “when America sneezes, the rest of the world catches a cold”, what we seem to be nearing now is something more closely approximating to pneumonia.

SUPPLEMENT

Here, as requested, are equivalent charts for New Zealand:

#198. The Theseus gambit

THE THREAD OF RATIONAL INTERPRETATION

According to Greek mythology, Theseus, having killed the Minotaur, found his way back from the heart of the Labyrinth by following a thread given to him by Ariadne.

There are two lessons – in an earlier idiom, morals – to be taken from this story. The obvious one is the wisdom of taking a thread into the maze and using it to find the way back out. The less obvious lesson is that the thread Theseus followed was reliable, a guide which, like real gold, would pass an ‘assay’ of veracity.

Our current economic and broader circumstances merit comparison with the Labyrinth – we’re in a maze which has many complex blind-alleys, routes to nowhere which tempt the unwary. If we’re to fashion a reliable thread that can be followed through it, we need to apply the assays of logic and observation.

The thread followed here starts with the purposes of saving and investment, purposes which pass the assay of logic, but fail the test of observation. This points to dysfunction based on anomaly, the anomaly being that the practice only conforms to the principle in the presence of growth.

Postulating that the economy is an energy system rather than a financial one also passes the assays of logic and observation, and confirms we have a thread that can be followed to meaningful explanations and expectations.

An assay of logic

Capital theory is as a good a place to start as any. This theory is that, in addition to meeting current needs and wants, a sensible person puts aside a part of his or her income for the purposes both of having a reserve (“for a rainy day”) and of accumulating wealth. The flip-side of this process is that saving – as ‘economic output not consumed’ – provides capital for investment. This theory would apply, incidentally, even if some form of barter were substituted for money.

For this to work, the saver or investor must receive a real return on investment that is positive (that is, it exceeds inflation), and this return must be calibrated in proportion to any risk to which his or her investment is exposed. The user of this capital must earn a return on invested capital which exceeds the return paid to the investor. Any business unable to do this must fail, freeing up capital and market share for more efficient competitors.

This thesis rings true when measured on the ‘assay of logic’ – indeed, it describes the only rational set of conditions which can govern productive and sustainable relationships between saving, investment, returns and enterprise.

But it’s equally obvious that this does not describe current financial conditions. Returns to investors are not positive. These returns are not calibrated in proportion to risk. Businesses do not need to earn returns which exceed appropriate returns being paid to investors. Businesses unable to meet this requirement do not fail.

When logic points so emphatically towards one set of conditions, whilst observation leaves us in no doubt that contrary conditions prevail, we don’t need to venture further into investment theory in order to confirm the definite existence of an anomaly.

To discover the nature of this anomaly, let’s look again at capital theory to discover the predicates shared by all participants.

The investor needs returns which increase the value of his or her capital.

The entrepreneur needs returns which are higher again than those required by the investor.

The shared predicate here is that the sum of money X must be turned into X+.

For the system to function, then, the shared predicate is growth.

Logic therefore tells us two things. The first is that a functioning capital system absolutely depends on growth. The second, inferred-by-logic conclusion is that, if the system has become dysfunctional, the absence of growth is likely to be the cause of the dysfunction.

Observed anomaly is thus defined as a property of dysfunction, whilst dysfunction itself is a property of the absence of growth.

You don’t need a doctorate in philosophy to reach this conclusion. All you need do is follow a logical sequence which (a) defines anomaly as intervening between theory and current practice, and (b) identifies this anomaly as the absence of growth.

We can confirm this finding by hypothesis. If we postulate the return of real, solid, indisputable growth into this situation, we can follow a sequential chain which goes on to eliminate the anomaly and restore the alignment of theory and practice.

Testing the thread

The deductions that (a) dysfunction exists, and (b) that this is a product of the lack of growth, take us on to familiar territory. If you’re a regular visitor to this site, you’ll know that the basic proposition is that the economy, far from being ‘a function of money, and unlimited’, is in fact a function of energy, and is limited by resource and environmental boundaries.

Using logic and observation, we can similarly apply the ‘assay of rationality’ to the propositions informing the surplus energy interpretation. There are three of these propositions or principles, previously described here as “the trilogy of the blindingly obvious”.

The first principle is that all of the goods and services which constitute economic output are products of the use of energy. If it were false, this proposition would be easy to disprove. All we’d have to do is to (a) name anything of economic utility that can be produced without the use of energy at any stage of the production process, and/or (b) explain how an economy could function in the absence of energy supply.

The second principle, applied here as ECoE (the Energy Cost of Energy), is that whenever energy is accessed for our use, some of that energy is always consumed in the access process. Again, if this proposition were false, its fallacy could be demonstrated, simply by citing any example where energy can be accessed without the use of any energy at any stage in the access process.

The third proposition – that money has no intrinsic worth, and commands value only as a ‘claim’ on the output of the energy economy – ought, if false, to be the easiest one to disprove. We would need to do no more, as a thought-exercise, than cast ourselves adrift in a lifeboat, equipped with very large quantities of any form of money, but with nothing for which this money could be exchanged. If this experiment succeeded, the ‘claim only’ hypothesis would be disproved.

The inability to disprove these propositions means that the theory of the economy as a surplus energy system passes the assay of rationality. Application is a much more complex matter, of course, but the next test is to see how theory fits observation.

The assay of observation

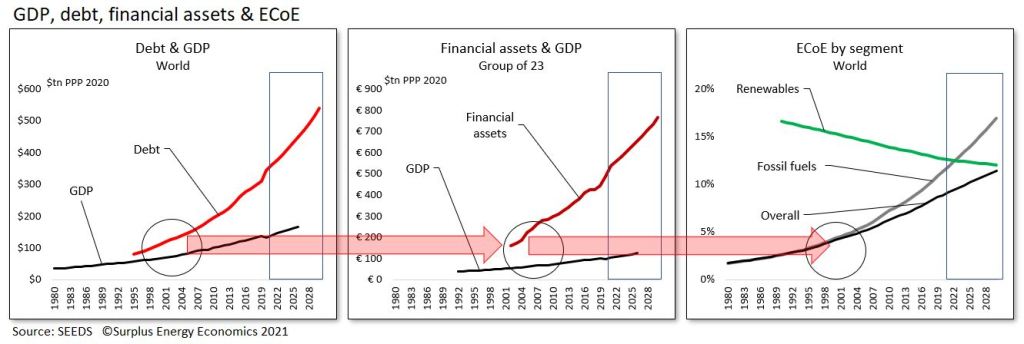

From the mid-1990s, and as the following charts show, global debt started to expand far more rapidly than continuing growth in reported GDP. Available data for twenty-three economies – accounting for three-quarters of GDP – shows a corresponding trend in the broader measure of ‘financial assets’, which are, of course, liabilities of the non-financial economy of governments, households and private non-financial corporations (PNFCs).

There is reliable data showing yet another correspondence, this time between the GDPs and the unfunded pension obligations (“gaps”) of a group of eight economies which include global giants such as the United States, China, Japan and India.

Let’s be clear about where this takes us. We’ve already identified the absence of growth as the source of financial dysfunction. We’ve now seen parallel anomalies in the relationships between GDP and liabilities.

These divergent patterns can be explained – indeed, can really only be explained – in terms of exploding financial commitments distorting reported GDP. Put another way, there are compounding trends whose effect is to ‘juice’ and to mispresent reported economic output.

This observation accords with the logical conclusion, discussed earlier, that the relationships between saving, investment, returns and enterprise have been distorted into a dysfunctional, anomalous condition by the absence of growth. The only complication is that we have to look behind reported “growth” numbers to make this connection.

What, though, explains the absence – in practice, the deceleration, ending and impending reversal – of growth itself? The right-hand chart indicates that what was happening at the start-point of observed economic distortion was a rise in ECoEs.

The assay that we’ve undertaken has shown the validity of the concepts of output as a function of energy, ECoE as a characteristic of the output equation, and money in the role of ‘claim’. This in turn validates the linkage identified here.

Fig. 1

Once again, let’s apply the test of hypothesis. Assume that a new source of low-cost (low ECoE) energy is discovered. Prosperity would increase, and real growth would return to the system. The observed anomalies in capital relationships would disappear.

This, remember, is purely hypothesis, because the discovery of a new source of low-cost energy is at the far end of the scale of improbability. We can thus conclude that dysfunction and anomaly will continue, to the climacteric at which the monetary system described by capital theory reaches a point of failure.

The clarity of defined anomaly

For anyone who isn’t a mythical hero, venturing into the Labyrinth, confronting the Minotaur and finding our way out again sounds like a terrifying experience. There are clear analogies to the present, in terms of the uncertainty of the maze, and the fear induced by the unknown. We may not have Ariadne’s thread, but we can fashion a good alternative by opting for rationality, applied through logic and observation.

The results of this process do seem to have the merit of clarity. Comparing capital theory with observed conditions identifies a dysfunction or anomaly that can be defined as the absence of growth. This in turn can be explained in terms of a faltering energy economy. Take away the predicate – growth – and the financial system becomes dysfunctional.

This interpretation helps to clarify the roles of the various players in the situation. Taking the ‘elites’, for example, we know that the defined aim of all elites is to maintain and, wherever possible, to enhance their wealth and influence. We can infer that, if we can identify the dysfunctionality of capital theory and observed conditions, so can they.

Likewise, we know that the defined aim of governments is the maintenance of the status quo, and we can again infer that they, like we, recognize the essential dysfunction as ‘the failure of the predicate’.

To this extent, we can demystify the behaviour of elites and governments. We can also make informed judgements on their probabilities of success. (These probabilities are low, for reasons which lie outside the scope of this discussion).

A similar application of logic and observation tells us that anomaly cannot continue in perpetuity. We can hypothesize the resolution of the energy-ECoE problem, but examination of the factors involved suggests that any such resolution, even if attainable, is unlikely to happen in time to restore equilibrium to the financial system. There are equations which relate the investment of legacy energy (from fossil fuels) into a new energy system (presumably renewables), and these equations give few grounds for optimism where current systems are concerned.

If rationality can take us this far, it surely makes sense to adhere to it. The probabilities are that global prosperity will contract, meaning that systems predicated on growth will cease to function. The logic of the situation seems to be that, when old predicates change, we need to fashion new systems based on their successors.

#197. “Life After Ideology”?

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF DE-GROWTH