UNCOVERING THE HIDDEN DYNAMIC

As you would expect, both the mainstream and the specialist media have been giving us minute-by-minute, blow-by-blow coverage of the financial crisis which began with the British government’s 23rd September “fiscal event”.

Unfortunately, this coverage and analysis is founded on a conventional school of economic thought which insists – rather, simply assumes – that all economic events can be explained in terms of money alone.

This assumption is fallacious. The fact of the matter is that we can immerse ourselves entirely in monetary theories and financial analyses until the proverbial “cows come home” without understanding more than the surface manifestations of the underlying situation.

As a corrective, let’s remind ourselves of something that ought to be self-evident. This is that the economy is a system which delivers those material products and services which together constitute prosperity. Money is simply a proxy for these products and services, a means of exchange and distribution which does not, of itself, determine the availability of this material prosperity.

This ‘money-only’ fallacy delivers false comfort, in at least two ways.

First, it enables us to explain away the current crisis in terms of idiosyncrasies – there’s a surface narrative which assures us that, if we can avoid the kind of bungling in which the new British leadership has become enmeshed, we can similarly avoid the kind of crisis now unfolding in the United Kingdom.

We might, indeed, be persuaded that even Britain can find a way out of this crisis through ‘rationalization’, which, in this case, might mean ‘finding rational people to manage its economic affairs’.

Now that growth has reversed

The second source of false comfort is the mistaken assumption that finding the right blend of fiscal and monetary policies can deliver the nirvana of perpetual growth.

Put another way, the implication is that premier Liz Truss and chancellor (finance minister) Kwasi Kwarteng were right to seek a “growth” elixir, even if they have been wrong about the mechanism for doing so.

This is simply not the case. The economy is an energy system, not a financial one. The entire narrative of the past quarter-century has been one of economic deceleration and deterioration caused by adverse changes in the energy dynamic which determines material prosperity.

Critically, the trend Energy Cost of Energy (ECoE) has been rising relentlessly, a process which, having started by creating “secular stagnation”, has now pushed us into involuntary economic contraction.

Fundamentally, we’re at the end of a long period of rising prosperity built on low-cost energy from coal, petroleum and natural gas. There is, as of now, no like-for-like replacement for the energy value hitherto sourced from fossil fuels.

Whilst we might hope to find a successor to waning (and climate-harming) fossil fuel energy value, three reasonable caveats need be recognized about this hope.

First, it is by no means assured. Second, the resulting economy is likely to be smaller, meaning poorer, than the one we have today. Third, no such transition can happen now, or spare us from the consequences of the fallacious assumption that we can rely on ‘infinite economic growth on a finite planet’.

The fact of the matter is that there are no financial ‘fixes’ for material economic deterioration. Looking for such fiscal and monetary fixes simply piles additional risk onto a global financial system already inflated beyond the point of sustainability.

When the financial dust settles, we will be left with a contracting economy, one in which deterioration in material prosperity is compounded by continuing increases in the real costs of energy-intensive necessities.

Accordingly, what we are witnessing is a process of affordability compression. This has many consequences, of which two are most important. First, the ability of consumers to afford discretionary (non-essential) products and services has entered secular contraction.

Second, the compression of affordability is undermining the ability of the household sector to ‘keep up the payments’ on a gamut of financial commitments ranging from mortgages and consumer credit to staged-purchase schemes and subscriptions.

In short, we can now project a future in which discretionary sectors contract relentlessly – with all that that means for employment, profitability and asset values – whilst the world’s gigantic system of interconnected financial liabilities unravels, with the latter process far likelier to be rapid and chaotic than gradual and managed.

A not-so-simple story

The superficial narrative of the current crisis pins the blame squarely on the new leadership of a single (though sizeable) Western economy.

The conventional story is that Ms Truss and Mr Kwarteng sought to find a way in which Britain could break out of a long period of economic underperformance. They decided to do this by cutting taxes, with the benefits skewed towards the better-off, perhaps in the belief that the much-derided theory of “trickle-down economics” might be valid after all.

These tax cuts, added to the decision to cap energy prices for households and businesses, threatened to create an enormous need to raise money by selling gilts (government bonds) to investors. This problem was compounded, first by the known intention of the Bank of England to unload gilts as part of a QT programme and, second, by the absence of the modelled and reasoned data and projections customarily provided by the Office for Budget Responsibility.

This ill-thought-out package occurred at a time of high inflation, to which it was known that the Bank intended to respond with rate rises and QT.

Markets responded to this ill-considered intervention in two ways, both of which should have been anticipated. First, FX markets sold off sterling, with GBP falling to slightly over $1.03, from levels above $1.22 just a few weeks previously. Second, the gilts market crashed, with yields on the 10Y bond spiking to over 4.5%, from 2% as recently as August.

This produced a toxic combination of expectations. A falling exchange rate would increase the prices of imports, driving inflation higher and, perhaps, forcing the Bank into a programme of accelerated monetary tightening involving rate hikes and QT.

Meanwhile, higher rates would increase borrowing costs, pushing property prices sharply downwards and, in all probability, triggering a wave of defaults on secured, unsecured and business debts.

In the event, nemesis came from a different quarter, with the viability of pension funds put at risk by falls in the value of gilts. It was this consideration which pushed the Bank into panic mode, intervening with a reversion to QE.

Behind the folly

So far, this is – to paraphrase a British radio soap – just “an everyday story of idiot folk”. Britain’s fiscal credibility has been shot to pieces, with one observer referring to the UK as a “submerging economy”. Policy folly has been compounded by a paralyzing sense of utter incompetence, with criticism extended from the executive leadership to the Bank.

Opposition politicians must have struggled to hide their partisan delight behind a façade of grave concern. Conservative MPs seem shell-shocked, worried as much about the prospect of plunging property prices as about marginal constituencies.

As objective observers, we need to look at this in different ways, of which one is specific to Britain, and the other more general. The common factor linking both is the belief in economic “growth”.

The British economy has long been living on borrowed time. The United Kingdom’s economic model is fundamentally flawed. Britain lives beyond its means, covering – but simultaneously exacerbating – its chronic current account deficit through the sale of assets. This is not sustainable, not least because a point is reached at which no saleable assets remain.

An economy thus structured relies on the continuous expansion of private credit. Credit expansion, in turn, requires both lender collateral and borrower confidence, and both have been provided by the inflated prices of assets, principally property.

There is, of course, an inherent contradiction here. On the one hand, the inflation of property (and broader asset) prices requires low and falling borrowing costs. On the other, debt expansion should, all things being equal, drive the cost of borrowing upwards.

Britain had already reached this point, as flagged by inflation, and as recognized by the Bank in its plans to raise rates and undertake QT. Even before 23rd September, the best that Britain could reasonably hope for was a “soft landing”.

QE, of course, is no more than a temporary ‘fix’. QE might not, at least pre-covid, have created retail price inflation – which is the only part of the pricing process that most observers bother to look at – but it has undoubtedly created reckless asset price inflation.

Both in Britain and elsewhere, systemic inflation – modelled by SEEDS as RRCI – has long been a great deal higher than the broad calculation expressed as the GDP deflator.

The wider issues

There is, though, a second and broader way in which we need to understand what’s really happening. The central mistake made by Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng was the assumption that there must be some combination of fiscal and monetary policies which could deliver the Holy Grail of “growth”.

Methods and policies may differ, but this belief in the possibility of infinite growth is shared by decision-makers – and corporate leaders, investors and the general public – right across the globe. The whole of the financial system worldwide is entirely predicated on the assumption of growth in perpetuity.

Conventional economics, with its fallacious assertion that the economy is entirely a financial system, fosters and endorses this mistaken assumption.

But the harsh reality is that the economy really functions, not financially, but as a system for delivering material prosperity in the form of goods, services, built assets and infrastructure. Self-evidently, all of this depends on the value obtained from the use of energy.

This isn’t simply a matter of the absolute quantity of energy that can be supplied. Rather, whenever energy is accessed for our use, some of that energy is always consumed in the access process. This ‘consumed in access’ component is known here as the Energy Cost of Energy, or ECoE.

Driven primarily by depletion, the ECoEs of fossil fuel energy have been rising exponentially. Since oil, gas and coal still account for more than four-fifths of total energy consumption, much the same has happened to overall trend ECoE. This has meant that aggregate prosperity has stopped growing, and prosperity per capita has already turned down.

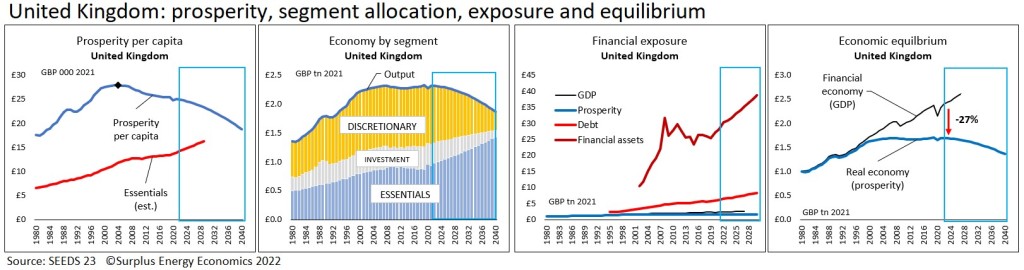

What this means is spelled out in the following charts. Just as top-line prosperity is falling, the real costs of energy-intensive essentials have been rising (first chart).

The inevitable result is that the affordability of discretionary purchases is falling, a trend that cannot be reversed, and can no longer be disguised by using cheap debt to prop up discretionary spending (second chart).

Financially, our wholly futile efforts to ‘fix’ material economic problems with financial expansion have created gigantic commitments which the economy of the future will be wholly unable to honour (third chart).

Lastly, the ‘financial’ economy of money and credit and the ‘real’ economy of energy-determined products and services have diverged, creating downside that the SEEDS economic model calculates at 40% (fourth chart).

This disequilibrium – rather than the ‘mistakes of incomprehension’ made at the national level – is the real explanation for the crisis into which, with utter inevitability, the world has now been pitched.

Fig. 1