REFLECTIONS ON A CRISIS

As soon as it became clear that the Wuhan coronavirus pandemic was going to have profound economic consequences, the aim here was to scope (since it is impossible for anyone to forecast) the implications for the financial system, and for the economy itself. Both have subsequently been converted into downloadable reports which can be accessed at the resources page of this site.

There’s no denying that both reports, stats-rich and based on the SEEDS model, are complex, even though every effort was made to combine clarity with a minimum of jargon. Indeed, ‘complicated’ might well define the whole situation with the coronavirus crisis.

Where once we might have said that ‘whole rainforests are being pulped’ to feed the appetite for comment and expression about the crisis, the 2020 equivalent is that the internet is becoming saturated with information-and-opinion overload.

The aim here is to take the issues ‘on the volley’, in hopes that this might tease out the nuggets of the important from the overburden of sprawl.

First, then, the pandemic itself. There seems no reason to doubt the severity of the health crisis, since neither governments nor businesses are prone to this kind of over-reaction – far from going out of their way to create panic, shake public confidence and cripple the economy, the political and economic ‘high command’ is likelier to promote false reassurance than to whip up unnecessary panic.

Neither do conspiracy theories seem particularly convincing. It seems pretty clear that the virus originated in China, but the idea of spill-over from dangerous experimentation seems far less plausible than the simpler explanation, which is that the virus jumped the species barrier in one of China’s dangerous, insanitary and, frankly, bizarre ‘wet markets’. Equally, it seems logical that an authoritarian, one-party state would react to an unknown threat with a habitual (rather than a pre-planned) denial, and with a bureaucratic, almost instinctive silencing of dissenting opinions.

Likewise, Mr Trump’s apparent belief that the World Health Organisation kowtowed to China by labelling the crisis ‘covid-19’ (rather than, say, ‘Wuhan flu’) seems less likely than the simpler explanation, which is that the WHO conformed to that same contemporary preference for euphemism which has presented the erosion of working conditions as the “gig economy”.

This isn’t to say, of course, that China isn’t looking for ‘the main chance’ where the pandemic is concerned. But it’s only fair to say that such opportunism is by no means a uniquely Chinese preserve. People from all shades of opinion, from every political persuasion and from all points of self-interest are trying to find their own silver linings in the coronavirus cloud. From calls for a world government to demands that “Brexit” be put on ice, we’re seeing hobbyhorses, even of the most irrelevant kind, being ridden to exhaustion.

By the same token, the use of lock-downs seems, on the whole, to have been a sensible response, because a distinguishing feature of the Wuhan virus is its rapidity of spread. The only real mystery about this is why, in an age of digital communication, a policy of physical separation is being mislabelled ‘social distancing’.

Of course, lock-downs come at a huge economic and broader cost, automatically prompting the public to wonder how much longer this situation will prevail. It’s a fair bet that governments around the world are contemplating ‘exit strategies’, but only the rash would insist on governments going public on what those strategies might be.

The priority now has to be to ensure that the public adheres to the principles of lock-down, and that resolve could only be weakened by premature speculation about how this might end.

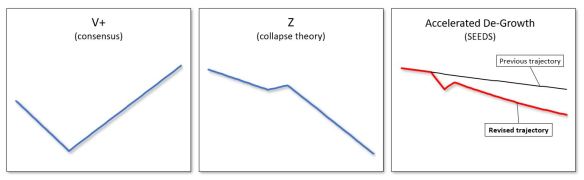

For their part, economists and others are trying to gauge the possible or probable extent of the damage that the coronavirus and the consequent reductions in activity are going to inflict on the economy. Though Britain’s OBR has presciently warned of the risk of longer-term “scarring” of the economy, the general supposition seems to be that, whatever the severity and the duration of the crisis turn out to be, it will be followed by a “recovery”, involving both the eventual restoration of pre-crisis levels of activity, and a reinstatement of the belief in “growth”.

The view expressed here is that trust in a full economic “recovery” – irrespective of the time that is allowed for this to happen – owes more to obstinacy and wishful-thinking than it does to logic. The very word “recovery” presupposes that the economy pre-virus was robust, was continuing to deliver meaningful “growth”, and constituted some form of “normality”.

It’s worth remembering that, long before the crisis, world trade in goods, and sales of everything from cars and smartphones to chips and electronic components, had already turned down. Financially, extreme strains were already emerging right across the system. Investors had already started turning their backs on shale, and the “unicorn” absurdity – the bizarre delusion that any company combining an “app” with a cash incinerator must come good in the end – was already going the same way as the Emperor’s New Clothes.

There is, after all, precious little “normality” to be found in a system which pays people to borrow, and which places an almost mystical faith in the ability of central banks to ensure that asset prices only ever move upwards.

No apology need be made for saying that a lot of us had already realised that the “new normal” – of ever-rising asset prices, and of an unending tide of cheap credit and cheaper money – had become absurd to the point of the surreal. The best reason, in addition to simple observation, for questioning the validity of this “new normal” mindset was a recognition that the economy is an energy system, and that the energy equation driving prosperity had already turned against us.

Rather than going into the technicalities of the energy-based interpretation, we can simply state that the relentless rise in the Energy Cost of Energy (ECoE) was applying a tightening squeeze to the surplus energy which determines prosperity.

The very extent of the financial adventurism happening in plain sight attests to the scale of bafflement and denial being required of the adherents of the dogma of perpetual growth. It doesn’t help, of course, that our entire financial system is wholly predicated on the implausible proposition that there need be no limits to economic expansion on a finite planet.

The reality, then, is that an ending of growth – and a consequent destabilising of the financial system – were lying in wait for us, needing only a catalyst, which the coronavirus has now supplied.

What this means is that “de-growth” has now arrived. This is not something that we have chosen, however compelling may have been the environmental or the human case for kicking our growth addiction. There’s nothing noble, voluntary or selected about the onset of de-growth which, rather, is a straightforward consequence of the unwinding of an energy dynamic which, courtesy of fossil fuels, has powered dramatic expansion ever since the first efficient heat-engine was unveiled back in 1760.

The necessity now is to understand de-growth, and to make the best of it. Those who have considered this likelihood have started to understand processes such as loss of critical mass, the threat posed by falling utilization rates, the inevitability both of simplification and of de-layering, and the equal inevitability that, just as economies became more complex as they expanded, they will be subject to a process of de-complexification now that prior growth in prosperity has gone into reverse. As shown below, these components of de-growth give us an outline taxonomy of the very different economic world of the future.

It doesn’t require a Pollyanna approach to understand that, just as “growth” has been a mixed blessing, de-growth offers opportunities as well as threats.

If you really valued ‘business as usual’, were looking forward to a world of widening inequalities and worsening insecurity of employment, enjoyed the glitz of promotion-drenched consumerism, and were unconcerned about what a never-ending pursuit of “growth” might do to the environment, you might find the onset of de-growth a cause for lament.

If, on the other hand, you understand that our world is not defined by material values alone, you might see opportunities where others see only regrets.

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = =