AN INTRODUCTION

In response to the previous article, it was suggested that it would be helpful if we had a comprehensive statement, a sort of Surplus Energy Economics 101, for new readers. This makes a great deal of sense, particularly given how many people have joined the SEE readership since the last time the thesis was set out in this way. The plan is that the article which follows will be made available as a downloadable PDF in the near future.

The aim here is to encompass two themes in a single article. The first is the basic logic informing the Surplus Energy Economics approach. This builds on the long-established principle that the economy should be understood as an energy system, not a financial one.

The second is an evaluation of where we are today on the evolution of the economy as energy interpretation explains it. This makes extensive use of the Surplus Energy Economics Data System (SEEDS), which models the economy as an energy system.

PART ONE: PRINCIPLE

The best way to start is with the “trilogy of the blindingly obvious”. No-one new to the subject can go far wrong if they bear in mind these three principles.

1.1. The economy is energy

The first principle is that all forms of economic output – literally all of the goods and services which comprise the ‘real’ economy – are products of energy.

Nothing of any economic value or utility can be supplied without using energy. Energy can be defined as ‘a capacity for work’ and, historically, everything that we wanted or needed was produced using the labour (work) of humans and animals, plus some early application of the power of wind and water. That changed from the late 1700s, when we learned how to deploy the vast reserves of energy contained in fossil fuel (FF) deposits of coal, oil and natural gas.

There is an abundantly clear correlation between escalating use of energy and the massive increases in population numbers, and their economic means of support, since the late eighteenth century (see fig. 1).

It should be noted that other natural resources (such as foods and minerals) are energy products, too, since we can’t grow wheat, for example, or extract and process copper, without using energy to do so.

Fig. 1

1.2. Of cost and surplus

Second, whenever we access energy for our use, some of that energy is always consumed in the access process. We can’t drill an oil well, construct a refinery, build a gas pipeline, manufacture a wind turbine or a solar panel, or install a power distribution grid, without using energy, and neither can we operate or maintain them without it. The energy that is consumed in the supply of energy therefore comprises both a capital (investment) and an operating component.

This principle is central to the established concept of the Energy Return on Energy Invested (EROI or EROEI), in which the consumed, cost or invested component is stated as a ratio. In Surplus Energy Economics (SEE), the cost element is known as the Energy Cost of Energy or ECoE, and is stated as a percentage.

Understood in this way, any given quantity of energy divides into parts. One of these is the cost element, known here as ECoE. The other – whatever remains – is surplus energy. This surplus drives all economic activity other than the supply of energy itself. This makes surplus energy coterminous with prosperity.

We can, of course, use this surplus wisely or foolishly, and we can share it out fairly or inequitably. But what we can not do is to “de-couple” economic output from energy or, to be more specific about it, from surplus energy.

1.3. Money – only a claim

The third part of the “blindingly obvious” trilogy is that money acts only as a ‘claim’ on the output of the real (energy) economy. Money has no intrinsic worth, and has value only in terms of the things for which it can be exchanged. No amount of money – be it currency, gold or any other token – would be of any use whatsoever to somebody stranded in the desert, or cast adrift in a lifeboat.

PART TWO – APPLICATION

This, then, is how the economy works – we access energy (’losing’ some of it as a ‘cost’ in the process); we use what remains (the surplus) to produce goods and services; and we exchange these with each other using money.

Where, though, are we now, on the evolution of ‘surplus energy, prosperity and money’?

2.1. The short version

If you want a succinct answer to this question, it is that ECoE (the Energy Cost of Energy) is rising, relentlessly and exponentially. The exponential rate of increase in ECoE means that this cannot be cancelled out by linear increases in the aggregate amount of total or gross (pre-ECoE) energy that we can access. The resultant squeeze on surplus energy has been compounded by increasing numbers of people seeking to share the prosperity that this surplus provides.

As a result, prior growth in prosperity per person has gone into reverse. People have been getting poorer in most Western advanced economies (AEs) since the early 2000s. With the same fate now starting to overtake emerging market (EM) countries too, global prosperity has turned down. One way of describing this process is “de-growth”.

In recent times, we’ve tried to use financial gimmickry – credit and monetary adventurism – to counter this adverse trend. Since money acts simply as a claim on economic output generated by energy, this is wholly futile, and can be likened to “trying to fix an ailing house-plant with a spanner”. We’ve been piling up financial excess claims on prosperity at a rate that guarantees a crisis in the financial system. This crisis must take the form of value destruction, which may happen through ‘hard’ defaults, ‘soft’ inflationary destruction of the value of money, or some combination of both.

2.2. The ECoE process

The Energy Cost of Energy (ECoE) at any given time is a product of four factors or ‘drivers’. Each of these evolves gradually, so ECoEs need to be understood and applied as trends.

The first of these is geographic reach, and the second is economies of scale. Both of them push ECoEs downwards, and both can best be illustrated by reference to the petroleum industry.

Starting from its origins in the Pennsylvania of the 1850s, the oil industry spread across the globe in search of new, larger, lower-cost sources of production. At the same time, growth in the size of operations reduced unit costs by spreading the fixed costs of operations across a larger amount of oil produced, processed and delivered. Accordingly, the ECoE of petroleum supply fell steadily through the contributions of reach and scale.

The third ‘driver’, which pushes ECoEs upwards rather than downwards, is depletion. Quite logically, the most profitable (lowest cost) sources of any resource are accessed first, leaving less profitable (costlier) alternatives for later. As this process unfolds, ‘later’ arrives, with low-cost resources exhausted, and replaced by successively higher-cost alternatives. This is why depletion drives ECoEs upwards.

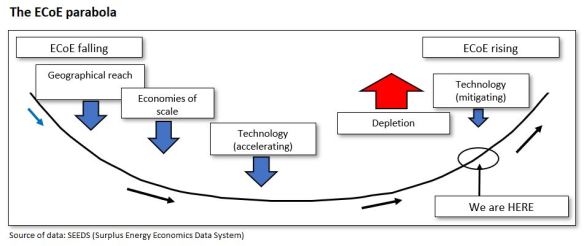

The four ECoE-determining factors – reach, scale, depletion and technology – can be put together in an illustrative parabola (fig. 2). In the early part of the sequence, ECoEs fall through the combined effects of reach and scale. As these drivers are exhausted, depletion takes over, forcing ECoEs back up again.

Fig. 2

Technology helps to accelerate downwards trends in ECoEs in the early part of the parabola, and then acts to mitigate increases on the upswing. It’s extremely important that we don’t get the role and potential of technology out of context. Technological potential is always limited by the ‘envelope’ of the physical characteristics of the resource.

For example, advances in fracking techniques have reduced the costs of extracting shale oil to levels lower than the cost of producing that same resource at an earlier time. What this has not done is to turn shales into the economic equivalent of large, conventional oil fields in the sands of Arabia – technology, then, cannot overcome the differences in physical characteristics between these resources.

2.3. The irresistible rise in ECoEs

As we’ve seen, the ECoEs of FFs have progressed along a historic parabola, and are now rising relentlessly. This trajectory is illustrated in fig. 3.

It must be stressed that the earlier part of the chart, shown as a dotted line, is simply illustrative – we don’t have enough data to know what ECoEs were in 1800, for example, or in 1900. We do, though, know enough about historical events, and about the processes involved, to have a pretty good general idea about where ECoEs were in earlier times. Evidence strongly suggests that a low-point – an ‘ECoE nadir’ – was reached in the two decades or so after 1945. This makes it wholly unsurprising – and not remotely coincidental – that this was a ‘golden age’ of growing prosperity.

Fig. 3

Looking at this historically, it’s noteworthy how two factors, not one, favoured the development of the Industrial Economy through a very extended period. Just as ECoEs were falling (thanks to reach, scale and technology), so the total supply of FF energy was increasing as well. This meant that we enjoyed a ‘virtuous circle’ in which the supply of surplus (ex-ECoE) energy was rising more rapidly than the total (‘gross’) availability of energy.

The situation today, though, is that the reverse applies, with a ‘vicious circle’ rather than a virtuous one. Just as trend ECoEs are rising relentlessly, so our ability to carry on increasing the gross supply of energy is being undermined, not just by the depletion of resources but also by the way in which rising ECoEs are undercutting the economics of the energy industries themselves.

To remain viable, these industries need to sell energy at prices which are both (a) above costs of supply, and (b) affordable to the consumer. The situation now is that, whilst costs are rising, increases in ECoE are also undermining affordability, by impairing the prosperity of the consumer.

In the period immediately preceding the coronavirus crisis, the consensus assumption was that total supply of energy was going to carry on rising at rates not dissimilar to those of the recent past.

Three authoritative suppliers of forecasts agreed that, by 2040, consumption of oil would be 10-12% greater than it was in 2018, that the use of gas would have grown by 30-32%, and that even the use of coal would not have decreased. Along with this would go an increase of about 75% in global vehicle numbers, and of about 90% in passenger aviation.

To those of us who understand the energy economy and the trends in ECoEs, these were never realistic projections.

2.4. Renewables – imperative, but not an economic ‘fix’

As the ECoEs of FFs continue to rise, and as concern increases over the threat to the environment posed by emissions, many believe that a “transition” to renewable energy (RE) sources will transform the situation.

We should be in no doubt that, on economic as well as environmental grounds, transition to REs is imperative. Continued reliance on FF energy might or might not wreck the environment, but would definitely wreck the economy, as the ECoEs of oil, gas and coal continue their relentless increases.

There are, though, two reasons for doubting the ability of REs to underpin economic prosperity by driving overall ECoEs back down the parabola.

The first of these is that RE remains essentially derivative of FF energy. We cannot (yet, anyway), build a wind turbine using only wind power, or a solar panel using solar energy alone. For the foreseeable future, the development of RE capacity will remain reliant on inputs whose availability depends on the use of energy sourced from FFs.

This limits the potential for further reductions in the ECoEs of energy sources such as wind and solar power, tying these ECoEs to the (rising) energy costs of fossil fuels. This is why, as shown in fig. 4, it’s unrealistic to assume that the ECoEs of REs will fall indefinitely, the likelihood being that the linkage will limit further declines in RE ECoEs, and could start to push them back upwards.

This linkage is reflected in the truly gigantic costs (which have been put at between $95 and $110 trillion) of transitioning from an FF to an RE economy. It doesn’t help, of course, that we’re reluctant to accept that the structure of an economy powered by RE electricity must differ from one powered by FFs. In the transport sector, for example, the portability of oil has favoured cars, but trams would make far more sense in an economy powered by electricity.

Fig. 4

The second limiting factor for a transition of the industrial economy to REs is that their ECoEs may never be low enough.

SEEDS modelling indicates that prosperity turns down at ECoEs of between 3.5% and 5.0% in the advanced economies, and between 8% and 10% in the less-complex EM countries (see fig. 8 at the end of this report). The likelihood is that the ECoEs of renewables may fall no further than 8% (at best, with 10% more probable). This would certainly make REs competitive with FFs (on a straight ‘ECoE to ECoE’ comparison), but it wouldn’t be low enough to stem, still less to reverse, the decline in prosperity that is already taking place.

This leads us naturally to the subject of prosperity, but it’s necessary, first, to look at how financial manipulation (‘adventurism’) has simultaneously (a) failed to shore up “growth”, (b) obscured what’s really happening to the economy, and (c) created enormous systemic risk.

2.5. GDP – a victim of distortion

As we’ve seen, money acts simply as a claim on the goods and services produced by the energy economy. Unfortunately, though, the energy basis of all economic activity has never gained recognition at the level of official decision-making, which instead continues to adhere to, and act upon, the belief that economics is ‘the study of money’, and that energy is ‘just another input’.

Accordingly – and heavily influenced by the contemporary fashion for deregulation – the authorities responded to the onset of deceleration in the 1990s by labelling it “secular stagnation”, and trying to ‘fix’ it using monetary policies.

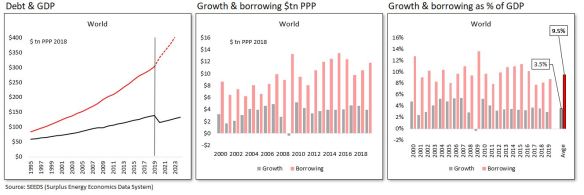

In the period preceding the 2008 global financial crisis (GFC), the emphasis was on ‘credit adventurism’, which involved making debt ever cheaper, and ever easier to obtain. The result was that, though the economy appeared robust, what was really happening was that apparent activity was being inflated by increases in credit. At the same time, world debt grew far more rapidly than reported GDP (see fig. 5), whilst risk not only increased, but became ever more diffuse and opaque.

When these trends triggered the GFC, the authorities set their faces against any kind of “reset”, opting instead to enact various forms of ‘monetary adventurism’. This hasn’t worked either, which is why the world entered the coronavirus crisis with (a) the financial system dangerously over-extended, and (b) no available policies, than those which have already failed so spectacularly.

From a surplus energy perspective, the critical point here is that borrowing has far exceeded “growth” through a twenty-year period in which average annual “growth” (of 3.5%) has been made possible by rates of borrowing which have averaged 9.5% of GDP (see the right-hand chart).

Fig. 5

This in turn means that a large proportion (more than half) of this “growth” has been cosmetic. This goes far beyond the simple ‘spending of borrowed money’, important though that has been. Monetary manipulation drives asset prices upwards, boosting the incomes of all of the many activities which are tied to assets. It also enables governments to provide services that, on an ex-borrowing basis, they could not afford to fund.

Even those people who haven’t piled on extra personal debt almost invariably have customers, or an employer, who has, whilst governments, by definition, borrow on behalf of all citizens.

The situation now is that, if debt was held at current levels (that is, it ceased to increase), global “growth” would slump, from a pre-crisis 3.5% to barely 1.0%.

If we tried to reduce debt to prior levels, much of the intervening “growth” would be reversed.

This leaves us with the third option of continuing to increase our debts, enabling incremental credit to keep flowing into the economy.

Unfortunately, this process creates a tension between liabilities and incomes which must result in one of two things happening. Either borrowers default on debts which they can no longer afford to service (let alone repay), or the authorities have to push so much new liquidity into the system that the value of currencies collapses in an inflationary spiral which constitutes ‘soft’ default.

Along the way, the collapse in returns on invested capital has played a major role in creating enormous gaps in pension provision, a situation that has rightly been dubbed a Global Pension Timebomb.

2.6. The economy – coming clean

What matters here is that financial manipulation, whilst it cannot (by definition) change the trajectory of energy-determined prosperity, can disguise the situation by manufacturing “growth” and “activity” through the creation of debt and other financial ‘claims’ that forward economic output will not be able to honour. (These are known as “excess claims” in SEEDS terminology, and are useful in the measurement of financial sustainability).

This gives us the choice of either (a) waiting for an enforced reset through a financial collapse, or (b) endeavouring to work out what is really happening to the economy behind the illusionary data presented, generally in good faith, to decision-makers, analysts and the public.

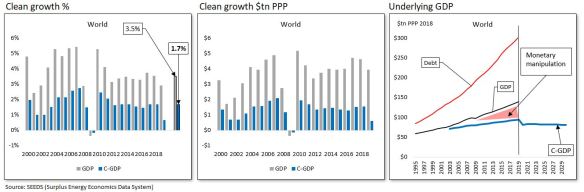

The latter course involves the calculation of underlying or ‘clean’ output by adjusting for the GDP distortion induced by credit and monetary adventurism. On this basis, we can identify clean growth, which averaged only 1.7% (rather than the reported 3.5%) between 1999 and 2019 (see fig. 6).

This provides a measure of underlying output (C-GDP) which, essentially, is what GDP would fall back to if we tried to deleverage the balance sheet back to prior levels of debt and other liabilities. Because debt is included in the right-hand chart in fig. 6, both sides of the distortionary linkage are readily apparent.

Fig. 6

2.7. The prosperity dimension

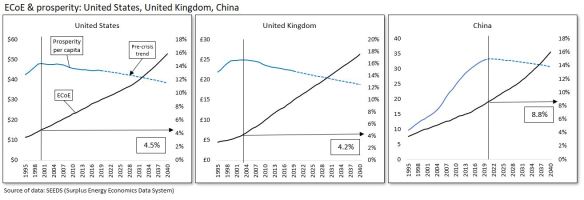

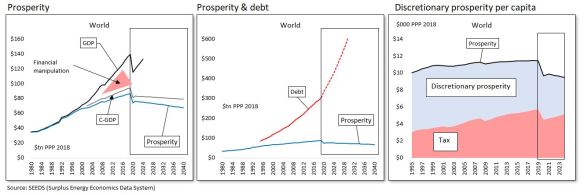

With C-GDP established, the deduction of trend ECoE enables us to measure prosperity, whether nationally, regional and globally, either as an aggregate or in per capita terms. Prosperity data is illustrated in fig. 7, in which all charts are calibrated in constant value international dollars, converted from other currencies using the PPP (purchasing power parity) convention.

The left-hand and centre charts show a situation that will, by now, be familiar, with reported GDP deviating ever further from the underlying situation (C-GDP), whilst debt escalates, and rising ECoEs drive a widening wedge between C-GDP and prosperity. When, as in the centre chart, we calibrate debt, not against (increasingly meaningless) GDP, but against prosperity, we see how financial exposure, with its growing component of excess claims, has become totally out of control. This situation would look even more acute, of course, if either aggregate financial assets (a measure of exposure), and/or gaps in pension provision, were also depicted.

Rising asset prices provide no useful offset at all, because these are purely notional valuations – they cannot be monetised, because the only people to whom these assets in their entirety could ever be sold are the same people to whom they already belong.

The right-hand chart shows one aspect of the challenge facing governments, as the ability to raise taxes is squeezed by deteriorating prosperity. This presents governments with the choice between curbing their expenditures, or creating hardship (and provoking anger) by worsening the squeeze on discretionary (“left in your pocket”) prosperity.

Fig. 7

We can and do, of course, take this analysis a great deal further. SEEDS data and interpretation is used to spell out the implications of de-growth; the extraordinary stresses facing every sector from the corporate and the financial to the realms of politics and government; and the insights that can be gained by applying the SEE understanding to our environmental challenge.

It is hoped, though, that this resumé summarises the logic, methods and conclusions of the Surplus Energy Economics approach in a comprehensive but convenient form. As a final reminder of how energy economics (and ECoE in particular) connect with prosperity, fig. 8 shows the relationships between the two, identifying the levels of ECoE at which prosperity per capita has turned down in the United States and worldwide and was, pre-coronavirus, poised to turn down in China.

Essentially, once trend ECoEs rise above a certain point, the average person starts getting poorer – a trend which no amount of financial tinkering can alter.

Fig. 8