EXPLORING THE TRANSACTIONAL CURVE

Why has the global economy become credit-addicted, and why has a post-capitalist kleptocracy replaced the market economy? Why is the much-vaunted transition to EVs decelerating, and why are the costs of renewable energy development rising? Can we really achieve nil-net-cost net zero, switching to more climate-friendly energy sources without becoming poorer in the process?

The answers to these and many other questions lie in economics, but not, as we shall see, in the way that economic issues are customarily presented to the public, and debated by decision-makers in business and government.

We can’t explain any of these trends by reference to money alone, but need to bring the material, and the laws of physics, into the equation.

Monetary experience, material substance

It’s understandable that the material gets lost in an economic system experienced in monetary form, Contracts of employment, for instance, don’t state that the employer will provide food, accommodation and transport in exchange for labour. Instead, the employee receives money with which to buy these necessities, hopefully with a margin left over for the purchase of discretionary (non-essential) products and services.

Whether we’re earning or spending, lending or borrowing, or investing for the future, we experience (and inter-act with) the economy in monetary form, but the prosperity of society, and the ways in which economic resources are allocated, are determined by the material.

In short, energy and materials are the substance of an economic system that is experienced financially.

What we’re going to discuss here is how the material has shaped the monetary over time, and how we can normalise the transactional curve to the underlying materiality of the economy.

For those who like some of their conclusions up front, the consensus narrative of a future in which everyone drives around in an EV powered by cheap and abundant clean energy isn’t going to happen, because it contravenes the limits of the material.

The rise of the post-capitalist kleptocracy can be traced to the sacrifice of market principles on the altar of a promised – but impossible – indefinite continuity of growth.

Whole sectors of the economy are heading into contraction and, in some cases, outright disappearance. We are witnessing massive malinvestment as capital is allocated to ‘growth’ sectors which have no real prospects of expansion. Some economies are far closer to the cliff-edge than has yet been realised.

Many of us would like to know how economic and broader trends are likely to unfold. Monetary trajectories alone cannot tell us this, but the harmonising of the monetary to the material can do so.

The basics – of materials and money

Effective interpretation of the economy requires the application of a concept wholly unknown in orthodox economics. This is the concept of two economies – a “real economy” of material products and services, and a parallel “financial economy” of money, transactions and credit. I introduced this concept in my 2013 book Life After Growth.

This concept is a necessity because, contrary to the insistence of the orthodoxy, the economy isn’t entirely, or even primarily, a financial system. Having no intrinsic worth, money has value only in terms of the material products and services for which it can be exchanged (the concept of money as claim).

By excluding the material, the economics orthodoxy manages to promise ‘infinite growth on a finite planet’, something which, in the words of Kenneth E. Boulding, co-founder of general systems theory, could only be believed by “a madman or an economist”.

The orthodoxy has various ingenious work-arounds for the finality of resources, but no amount of incentive, financial stimulus, substitution or innovation can supply something which does not exist in nature.

To be quite clear about this, we can lend money into existence, and central bankers can create it at a key-stroke, but we can’t similarly conjure energy or raw materials out of the ether. Natural resources are, by definition, finite in character.

When we think about natural resources, we tend to put fossil fuels, minerals, water and productive land into this category. But the environment, too, is a finite natural resource – it’s finite in its tolerance, meaning its ability to absorb the effects of human economic activity.

We know that the material exists. A long-ago writer said that we discover the reality of the material in infancy, when our first hesitant steps bring us into painful collision with the furniture. The human mind may struggle to grasp the concept of infinity, but we should have no trouble with comprehending the finite.

My efforts over the past decade have been concentrated on exploring, explaining and calibrating the “real” or material economy, and using it to benchmark the “financial” economy of monetary transactions.

We know how this “real economy” works, and it’s a matter of energy, raw materials and physics – not money.

Understanding the material

I don’t intend to go into technicalities here, but the biggest challenge of the SEEDS project has been to translate the substance of the material into the language of the monetary. The whole aim of the project has been to link the financial to the material.

Stated at its simplest, the physical economy functions by using energy to convert raw materials into products and services. The latter emphatically belong in this category, because no service can be provided without material assets, such as vehicles for delivering packages, and a network for the supply of on-line services.

We can no more render the economy ‘immaterial’ by displacing goods with services than we can somehow “de-couple” the economy from the use of energy. The latter is impossible because the economy IS an energy system.

As regular readers may know – but new visitors might not, and this simply can’t be reiterated too often – there are two distinct characteristics of the material economy which can guide us to effective interpretation.

The first is that energy is never “free”, and the second is that the critical characteristic of energy is its density, something which can be likened, for convenience, to the power-to-weight equation as it affects the performance of vehicles.

Energy is never “free”, because it cannot be put to use without a physical infrastructure. Oil and gas aren’t “free” because they exist beneath our territory, and renewables aren’t “free” just because the sun shines and the wind blows. We need wind turbines, solar panels, power storage systems and distribution grids for the harnessing of renewables, just as surely as we need wells, mines, pipelines and processing plants for the supply of oil, natural gas or coal.

This infrastructure is physical, meaning that its creation, operation, maintenance and replacement require raw materials. These raw materials cannot be accessed or processed without the use of energy.

Accordingly, putting energy to work is an ‘in-out’ process, in which, whenever energy is accessed for our use, some of this energy is always consumed in the access process. This ‘consumed in access’ component is known in Surplus Energy Economics as the Energy Cost of Energy, abbreviated ECoE.

The productive equation

The second material precept – the critical importance of energy density – can be explained by reference to the dual nature of the economic production process. When energy is used to convert raw materials into products, so energy itself is converted from a dense to a diffuse state.

These two processes are inseparably linked, so we can’t have the one without the other. In this productive-dissipative equation, if we shorten or truncate the dissipative process by reducing the density of energy inputs to the system, we correspondingly shorten the productive process, resulting in a smaller economy.

It’s regrettable, but undeniable, that renewables are less dense than fossil fuels. Transitioning to renewables may have environmental benefits – though even this claim needs to be treated with caution – but an economy powered by less energy-dense renewable energy must be smaller than an economy powered by more energy-dense oil, gas and coal.

The environmental (as well as the supposed economic) merits of renewables need to be heavily qualified, because a system based on less dense energy needs a correspondingly larger physical supply infrastructure. This in turn means an expanded need for raw materials, and this is likely to have many adverse environmental and ecological consequences.

Moreover, the accessing and processing of these raw materials increases the need for energy inputs. Indeed, the term “renewable” is questionable, because the only energy source capable of supplying everything from concrete and steel to copper, lithium and cobalt, in the quantities needed for transition, is legacy energy sourced from fossil fuels.

The energy-productive process thus described does not operate in a vacuum. Other critical factors include the quantity and quality of mineral resources and food-productive land. As mentioned above, a further critical resource is the natural environment, meaning the capability of the environment to absorb the effects of economic activity. Just like iron ore or arable land, environmental tolerance is a finite resource.

Not to infinity

The foregoing should frame our understanding of the sheer impossibility of ‘infinite economic growth on a finite planet’.

As well as being ultimately finite in character, natural resources interact with the economy in a specific way. Faced with choices, we always, and quite naturally, use the lowest-cost resource first, setting aside costlier alternatives for later. As this process progresses, it results in depletion, whereby each new resource becomes costlier than the one it replaces.

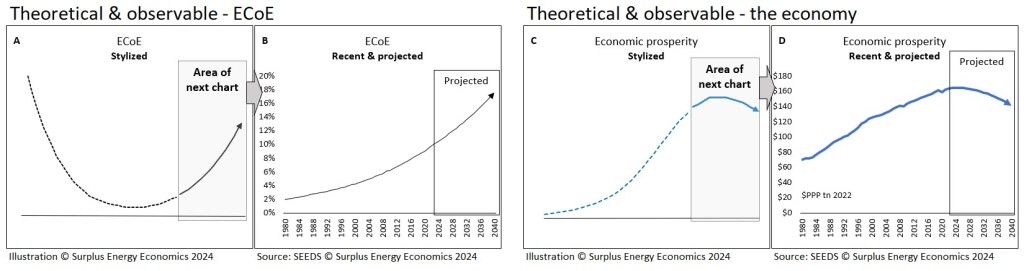

With energy, this results in a distinctive ECoE curve or parabola, illustrated in Fig. 1A.

Taking petroleum as an example, ECoEs declined as the industry explored the globe in search of larger, lower-cost reserves; as the expansion of the oil business yielded economies of scale; and as the technology used in the industry improved.

Eventually, though, the potential benefits of scale and geographic reach were exhausted, and depletion took over as the primary driver of ECoEs, which then turned upwards. There are strict limits to how far technological advance can offset this rising trend, because the potential of technology is limited by the physical characteristics of the resource.

Here’s an issue that we need to look fairly and squarely in the face. The dramatic growth in the size and complexity of the modern industrial economy is a direct consequence of harnessing the vast amounts of low-cost energy contained in the planet’s reserves of fossil fuels. Nothing like it had ever happened before.

Its continuity is entirely dependent on the discovery of alternatives, and these must be at least as energy-dense as oil, gas and coal.

We cannot rule out the discovery of a new energy source matching or exceeding the density of fossil fuels, but there are two observations that are extremely pertinent to our situation.

First, renewables aren’t going to provide energy of the necessary density. Second, we are rapidly running out of time for such a discovery, because the trend ECoEs of fossil fuels are rising very rapidly indeed.

Though we don’t have the data needed to track the ECoE curve back to the early years of the twentieth century and beyond, we can say two things, with considerable confidence, about the nadir of the fossil fuel ECoE curve.

The first is that it probably occurred in the quarter-century after 1945. The second is that the trend ECoE of fossil fuels was probably well below 1% at its lowest point. From 2% in 1980, and 4.2% in 2000, all-sources trend ECoE has already broken the 10% barrier, and is likely to reach 18% by 2040.

In the absence of some spectacular scientific discovery, trend ECoEs must carry on rising, and material prosperity must inflect from growth into contraction. This is shown in Fig. 1, in which stylized long-run ECoE and prosperity curves are paired with more recent trends for which data is available.

Fig. 1

We need to be in no doubt that, if this is what’s happening to the “real” economy of material products and services, the parallel “financial” economy cannot wander off in a different direction, because money is validated only by our ability to exchange it for the material.

As extreme disequilibrium emerges between the ‘two economies’, we cannot compel the material to conform to the financial, because the exchange value connection between them doesn’t operate in that direction.

From the material to the monetary

I said we wouldn’t go into technicalities in this discussion but, in outline, SEEDS analysis plots two distinct curves, globally, and for each of the 29 national economies covered by the model. The prosperity curve of the “real” economy, though material in character, is presented in monetary terms for the purposes of benchmarking and comparison with the “financial” curve.

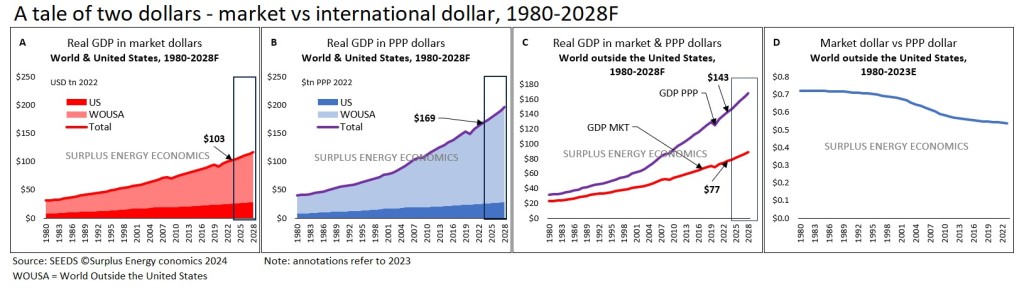

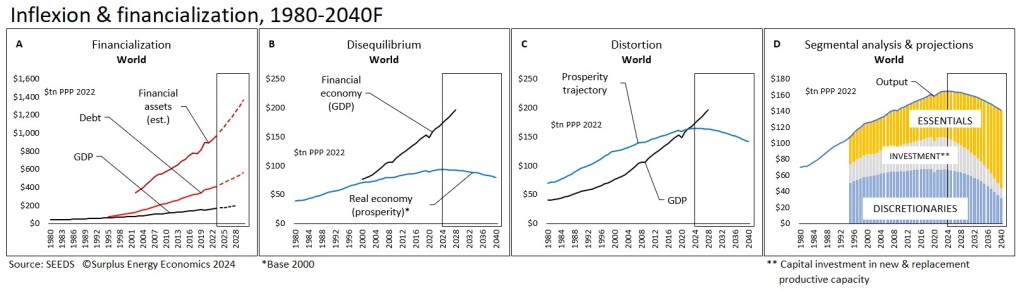

As you may know, GDP is a measure of transactional activity, not material economic output. As such, it is capable of distortion, not least by the injection of large amounts of credit into the system. Between 2002 and 2022, and stated at constant values, GDP increased by $83tn, or 103%, whilst debt expanded by $266tn, or 209%.

These are not discrete series, because the sole purpose of taking on credit is to spend it, meaning that growth in debt necessarily drives increases, unrelated to value, in the transactional activities measured as GDP. We can calculate that each dollar of reported “growth” between 2002 and 2022 was accompanied – and made possible – by a $3.20 increase in debt. Put another way, we had to borrow at an annual average rate of 11% of GDP to deliver annual average “growth” of 3.5% between those years.

Additionally, of course, no allowance is made for ECoE in the measurement of GDP. Trying to measure the economy without including energy in general, and ECoE in particular, is like staging Hamlet without the Prince.

The artificial ‘credit effect’ is something that happens over time, and this makes the analytical value of reported GDP equivocal. We probably can accept that $164tn is a reasonably accurate snapshot of transactional activity in 2022, but we can’t accept that this was an increase of 103% (real) over the previous twenty years, because of the distorting effects of credit creation over time.

Accordingly, if we want to know the real rate of change in the economy in past years, we need to retrofit (“harmonise”) transactional activity to the curve of the material. This is illustrated, on a global basis, in Fig. 2.

Using this same technique, we can project the economy forwards along the curve of material prosperity, and allocate output to the three critical segments of essentials, discretionary (non-essential) consumption, and capital investment in new and replacement productive capacity.

Conclusions

If we don’t mind stretching the relationship between the financial and the material, we can carry on, perhaps for a while longer yet, creating additional transactional activity by pouring new credit into the system. This describes the simulacrum of “growth” that economies have been reporting in the age of subsidised money.

But this doesn’t mean that extra economic value has been delivered, and the consequence of this process is that liabilities will rise to a point at which the likelihood of their ever being honoured ‘for value’ ceases to be credible. Market vertigo is going to be one of the main factors that triggers the coming financial crash.

The general conclusions of SEE analysis of transactional trends are wholly consistent with what we know about the economy from the standpoint of material analysis. Just as rising ECoEs are driving down the supply and ex-cost economic value of energy, so the real costs of energy-intensive necessities are being pushed upwards.

This can be expected to undercut returns on invested capital, such that capital investment decreases. As this happens, and as asset markets slump, the effect will be to expose enormous malinvestment. Calibrating the scope of this malinvestment, and determining where it has occurred, is perfectly feasible, but not in the compass of this article.

The affordability of discretionary products and services will be subject to leveraged compression, a process already visible in economies worst exposed to the “cost of living crisis”.

Discretionary compression will, of course, have financial as well as economic effects, undermining the ability of the household sector to carry its massively-expanded burden of financial commitments.

Where the economy itself is concerned, though, the process of discretionary compression is the trend to watch as material conditions continue to deteriorate.

Tim Morgan

Fig. 2