THE COMING FINANCIAL CRASH

One question, above all others, has dominated our recent discussions here. This is the issue of whether the financial system will fracture as the underlying “real” or material economy inflects from growth into contraction.

Has some kind of chaotic reset – either contractionary or hyperinflationary – become inevitable? Are we – to put it colloquially – heading into a re-run of the Wall Street crash and the ensuing Great Depression?

The answer is that we are. Only two outcomes remain possible. One is a cascade of defaults and asset price crashes, and the other is a full-on resort to money-creation, resulting in an uncontrollable surge in inflation.

The likelihood is that the latter will be tried, but will fail to prevent the former.

The financial system has been set up to fail.

To understand why, we need to follow trends in the relationship between the two economies – the “real economy” of material products and services, and the parallel “financial economy” of money, transactions and credit.

The road of folly

One of the main characteristics of financial markets is that they endeavour to price the future. Left to their own devices, they might well have done this effectively, pricing in a gradual and manageable contraction in the underlying economy.

Investors would have become increasingly risk-averse, switching from discretionaries into staples, and pulling back from non-sovereign credit exposure.

These are things that investors can still do, of course, but it’s no longer possible for this to happen in an orderly, gradual manner.

The system, though, far from being left to fulfil its functions of price-discovery and putting a price on risk, has been subjected to massive distortion, and compelled to price a future which cannot happen.

Decision-makers have followed a false mantra which decrees that monetary stimulus can deliver indefinite material economic expansion, a mechanism which cannot work in an economy butting up against energy, resource and environmental limits.

When the Western economies started to experience deceleration – “secular stagnation” – in the 1990s, this could have been traced to its causation in energy trends, and policies could have been adjusted accordingly.

Instead, the response was a resort to credit liberalisation. When this led, inevitably, to the global financial crisis of 2008-09, the authorities adopted ultra-loose monetary policies, with the twin aims of crisis-management and economic stimulus. The results were the inflation of a massive “everything bubble” in asset prices, and a surge in debt, much of it outside the regulated banking sector.

This has been an on-steroids re-run of the follies of the “roaring twenties”, made much more toxic by the unanchored fiat currency system that didn’t exist back in the 1920s.

This time, moreover, we’ve taken things so far that the essential principles of market capitalism have been abrogated. Markets are no longer left free to set prices and calibrate risk, whilst investors can no longer earn a real (above-inflation) income return on their capital.

We don’t yet know what kind of post-capitalist system will be ushered in by economic contraction, but no such system will be able to sustain a financial structure based on ever-expanding credit, designed to disguise economic contraction, and often used for gambling on successive failed themes.

The hard reality of inflexion

The history of the modern economy is one of gradual deceleration from growth into contraction.

This began in the advanced economies of the West, whose high levels of complexity render them especially sensitive to the force driving the global economic downturn, which is the relentless rise in ECoEs (the Energy Costs of Energy).

By virtue of the lower systemic upkeep costs which come with lesser complexity, most EM (emerging market) economies have, until recently, carried on expanding, but they, too, are now reaching the point on the ECoE curve at which the economy inflects from growth into involuntary de-growth.

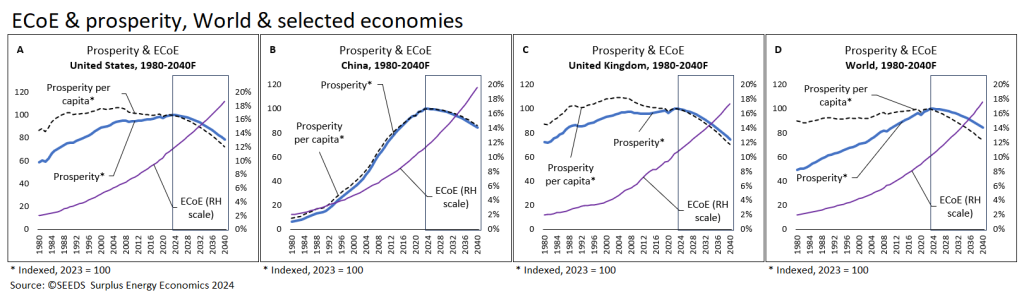

These processes are illustrated in Fig. 1, where total and per capita prosperity are indexed to 2023, and compared with trend ECoEs.

Fig. 1

This means that we are now at, or very near to, the global economy’s point of inflexion. Economic “growth” is still being reported, but most of this is the cosmetic effect of pouring ever more public and private credit into the system, and counting the spending of this money as “activity”. There’s not much value in recording, say, “growth” of 2% when the government has to run an 8% fiscal deficit to achieve it.

If you’ve been visiting this site for any length of time, you’ll know how the “real economy” of material products and services operates, and how prosperity is determined by the supply, value and cost of energy, operating within a broader context that includes non-energy natural resources and the limits of the tolerance envelope of the environment.

You’ll also know some, at least, of what lies ahead. Just as prosperity is going into decline, so the real costs of energy-intensive necessities are rising. Sectors supplying discretionary (non-essential) products and services to consumers have entered a process of worsening affordability compression.

Sales of smartphones have already inflected and, despite lavish support from taxpayers, the pace of adoption of EVs seems to be decelerating markedly. The news media and hospitality are amongst the sectors now entering discretionary contraction. Social media, entertainment and travel are amongst the industries closing in on this contractionary moment.

Discretionary contraction is going to create enormous job losses, but the longer-term outlook is for increasing displacement of machinery with human labour. This time around, we’re not likely to see armies of cloth-capped working men queueing up for government handouts but, rather, a haemorrhaging of middle-ranking technical, professional and specialist posts as businesses cut costs and streamline their operations.

We know that this process of inflexion is happening, and we know why. The large and complex modern economy was built on abundant low-cost energy from coal, oil and natural gas. The costs of these fossil fuels are rising relentlessly because we have, quite naturally, used lowest-cost resources first, leaving costlier alternatives for a ‘later’ which has now arrived.

This process has been subjected to extensive investigation by many people around the world and, here at Surplus Energy Economics, has been modelled using SEEDS.

We have no equal-value alternative to fossil fuel energy, meaning that the material (ECoE) cost of energy will carry on rising, and the economy will contract. The costs of energy-intensive necessities will carry on rising, investment in new and replacement productive capacity will shrink and, most importantly of all, the ability of households to afford discretionaries – the things that people might want, but don’t need – will be subject to relentless contraction.

This doesn’t just mean that households will have to get by without various non-essentials hitherto taken very largely for granted. It also means that they will find it increasingly hard to ‘keep up the payments’ on everything from secured and unsecured credit to subscriptions and staged-payment purchases.

In an economy shaped by energy, there’s no bottomless well of household financial resources, and any attempt to create one using ultra-loose monetary policies can only lead to the hyper-inflationary destruction of the purchasing power value of money.

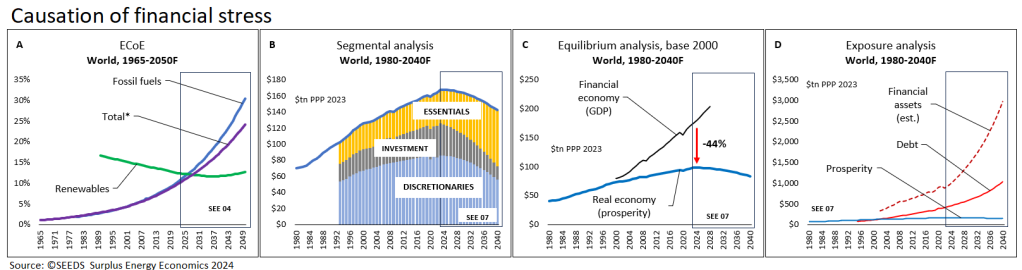

The outlook for the material and financial economies is quite clear, and is pictured in Fig. 2.

Structurally, the departure of the “financial economy” (of money, transactions and credit) from the underlying “real economy” (of material products and services) has introduced enormous disequilibrium pressure into the system (Fig. 2C), pressure that has been rising even as the aggregates of debt and broader liability exposure have been escalating (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2

What next?

Within our general understanding of economic and financial causation, two big questions remain to be answered. First, what’s going to happen to domestic and international politics as the public, previously promised perpetual material betterment, awakes to the reality of deteriorating prosperity, narrowing choices and worsening insecurity?

Second, can the financial system, in its present form, survive the inflexion of the material economy from growth into contraction? The short answer to this question is that it can’t, and the task ahead is to redesign the financial system for a smaller, supportive role in a shrinking economy.

The political issue requires a discussion all to itself, but we can already see popular dissatisfaction finding voice in the rise of authoritarian populism. If people are assured that growth is continuing, whilst their own circumstances are getting steadily worse, what conclusions can they be expected to draw?

They might conclude that all the talk about growth is fiction, but they’re likelier to suspect that, whilst growth is indeed continuing, all, and more, of the benefits of this growth are being cornered by a small, dishonest and self-serving minority.

If the current rise of populism seems like an echo of the years between 1918 and 1939, there are some other striking similarities between what’s taking place now and what happened in those inter-war years.

Whilst history never repeats itself, there are recurring patterns, and Tim Watkins is to be commended for reminding us of the main economic feature of the inter-war years. In essence, the coal-based economy was decelerating into contraction at a time when the oil economy wasn’t – quite – ready to replace it.

Now, the oil economy itself is inflecting but, this time around, there’s no new, higher-value energy source waiting in the wings to take over.

The cresting of the coal economy, and the gap that intervened before oil was ready to take over, might sound like a minor glitch, a temporary, if irritating, snag with time-phasing. But it was anything but minor for those who had to live through it.

First, in October 1929, came the Wall Street crash, an event made so serious by the run-up of prices (and euphoria) during the reckless years of the “roaring twenties”.

Next came the miseries of the ten-year Great Depression. The hardship (and unfairness) of the depression years played right into the hands of demagogues, including Hitler, Mussolini, and the nationalist-expansionist faction in Imperial Japan. The rest, as the saying goes, “is history” – a war that killed between 70 and 85 million people, followed by a recovery powered by oil.

How far are these patterns likely to recur?

These are matters of behavioural factors intersecting with economic trends, and it’s useful to reflect for a moment on how a superior intelligence, watching from the depths of space, might view our current predicament.

This intelligence would marvel at the behaviour of homo idioticus which, already experiencing severe environmental and ecological degradation and, conceivably, heading into a Holocene extinction event, carries on driving, flying, mining, consuming, polluting and landfilling as though nothing other than consumption matters at all.

This superior intelligence might find humour in our efforts to deny reality with endless exercises in financial gimmickry, and might wonder – since there are no investment analysts on the Moon, or credit rating agencies on Mars – who exactly we’re trying to impress or deceive.

With the important difference of using an untethered fiat currency system, we’ve been re-running the “roaring twenties” on an enormous scale. The narratives used to ‘justify’ hyper-inflated stock and property prices become increasingly implausible, the latest one being predicated on AI putting to rights everything that human intelligence has got wrong.

We’ll have to go through a GFCII event, this time on a scale that no amount of monetary gimmickry can buy off. Then we’ll have to build a new financial system, just as individual countries have been compelled to do after the hyperinflationary destruction of their currencies.