ARE DISCRETIONARY PURCHASES NO LONGER AFFORDABLE?

When somebody makes a discretionary (non-essential) purchase – pays for a leisure activity, for instance, or a consumer gadget, or a holiday – the assumption is that he or she ‘can afford it’. But the World economy runs on continuous infusions of credit, which makes the world “afford” subject to increasingly severe qualification.

This discussion presents an analysis of prosperity (as opposed to credit-financed ‘consumption’), in conjunction with assessments of taxation, and of the cost of household essentials. It indicates that the average person can not now afford discretionary purchases. Moreover, his or her ability to afford liens on income – the household counterparts of the streams of income now so critically embedded in an increasingly financialized economy – has to be open to very serious question.

As we near the point where we exhaust our ability to inflate economic ‘activity’ with perpetual credit injection, we are poised to make two very disturbing discoveries. The first is that swathes of discretionary activity are no longer affordable on a sustainable basis, to the point where sectors supplying these purchases are to a large extent living on the life-support of financial manipulation.

The second is that a large proportion of asset valuations – where they involve discretionary suppliers, capitalized streams of income, and property – are hanging by a thread.

Introduction

In the previous article, we went in some depth into the workings of the economy as an energy system, concluding that prior growth in prosperity has gone into reverse as the energy equation has deteriorated. The aim here is to explore some selected implications of the onset of “de-growth”.

This can best be done, not by looking only in a ‘top-down’ way at institutions, systems and enterprises, but by following a ‘bottom-up’ rationale which starts with the circumstances of the ‘average’ or ‘ordinary’ person.

The central realities are (a) that this ordinary person’s prosperity is shrinking, and (b) that conventional definitions of economic output and individual income greatly overstate the economic resources to which he or she has access.

There is a sequence of hierarchy in how the ‘average’ person spends his or her income. The first calls are taxation, and the cost of household essentials. Next come various liens on income owed to the financial and corporate system – these are the household counterparts of the streams of income on which so much corporate activity and capital asset value now depend. ‘Discretionary’ (non-essential) spending – everything from leisure and travel to the purchase of durable and non-durable consumer goods – is funded out of what remains, after these various prior calls have been met.

Putting these two facts together leads to some striking conclusions. Because discretionary consumption comes last in the pecking-order of spending – and because a large and growing slice of apparent ‘income’ is no more than a cosmetic product of financial manipulation – then it follows that the underlying and sustainable level of discretionary expenditures is far lower than is generally assumed.

In essence, discretionary sectors of the economy are now on life-support, kept in being only by the drip-feed of credit and monetary stimulus. Additionally, the ability of households to sustain the stream-of-income payments to the financial and corporate sectors is hanging by a thread.

This means, first, that, as and when credit and monetary adventurism reach their practical limits, whole sectors of the economy will contract very severely.

Second, it means that we have reasonable visibility on the processes by which asset prices will slump into a new equilibrium with much-reduced economic prosperity.

Critical path

These findings have profound implications, so much so that it’s important to understand the analytical route by which they have been reached. This discussion follows a path which starts with a top-down examination of how the ‘real’ economy of goods and services actually functions, translates this into what it means for the ‘average’ or ‘ordinary’ person, and proceeds from there to various findings relevant to business, finance and government. This analysis is informed by the proprietary SEEDS economic model, which presents energy-based analysis in the financial ‘language’ in which, by convention, debates over these issues are conducted.

If you’re new to energy-based interpretation of the economy, the ‘big picture’ is simply stated.

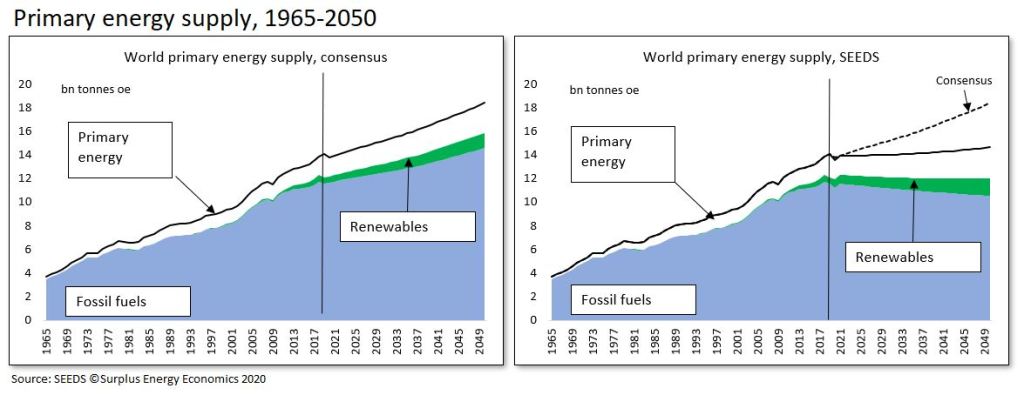

Essentially, the dramatic growth in economic output (and in the numbers of people supported by that output) since the 1760s has been a function of cheap energy from coal, oil and natural gas.

More recently, three trends have undermined this dynamic. First, fossil fuel energy has ceased to be ‘cheap’, in meaningful, energy-margin terms.

Second, this cost increase is taking away our ability to maintain (let alone to further increase) the supply of fossil fuels.

Third, we have reached – or passed – the limits of environmental tolerance of an economy powered by fossil fuel energy.

This means, either that we find an economic replacement for oil, gas and coal, or that we adapt ourselves to the ending of the fossil fuel prosperity dynamic. The authorities, who are aware of the environmental but not the economic implications of this situation, are pinning their hopes on transition to renewable energy sources (REs).

The environmental case for transition to REs is undoubtedly compelling. But the belief that REs can replicate the economic impetus of fossil fuels, far from being ‘proven’, is simply an assumption, based primarily on wishful thinking, and, far from success being assured, the probability of it happening is actually very low.

Considered in ECoE terms, whilst the costs of RE supplies are falling, they are unlikely ever to be low enough to replace the fossil fuel growth dynamic. The building out of RE capacity continues to rely on inputs which only the use of fossil fuels can provide. We cannot – yet, anyway – build solar panels using only solar energy, or construct wind-turbines using wind power alone.

Moreover, we should not assume that REs can ever be a like-for-like replacement for oil, gas and coal. An economy powered by REs will not replicate the one built on fossil fuels. The push to replace internal combustion engine (ICE) transport with electric vehicles (EVs) is a case in point. Whereas the properties of petroleum favoured the development of cars, RE-provided electricity is likely to work far more effectively as a power source for public transport.

Even if (and it’s a big ‘if’) RE electricity can replace the quantity of energy used by ICE vehicles, batteries cannot replicate the characteristics of the fuel-tank. If we try to ‘buck the physics’ on this – if we insist on clinging on to cars, rather than switching to trains and trams – then we risk, not only a costly failure, but also an environmental disaster caused by mining the materials necessary for the requisite supply of batteries.

In parenthesis, it’s only fair to note that the authorities very probably don’t anticipate like-for-like replacement of ICE cars with EVs, but they can hardly tell voters that car ownership is set to fall markedly.

Economic conditions – the personal factor

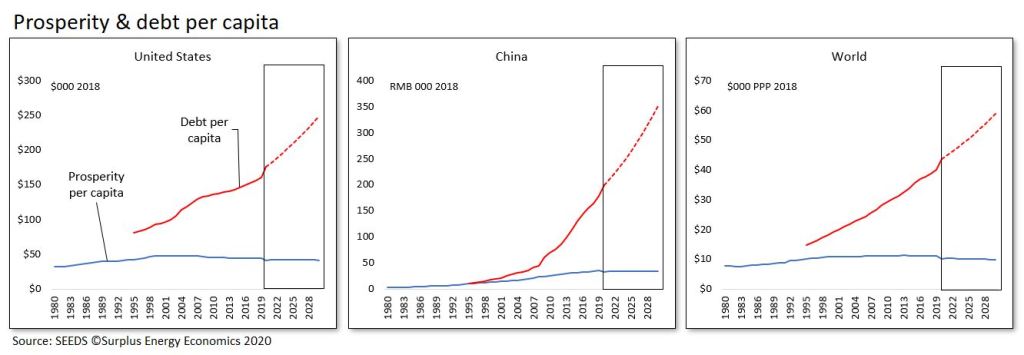

Where this top-down situation leaves our ‘average’ person is with deteriorating prosperity. It might not look that way to him or her, but this is because both macro and micro perceptions have been obscured by the use of financial ‘innovation’, which has included sub-zero real interest rates (by which people are paid to borrow), and monetary expansion (which back-stops this escalation in debt and other obligations).

Wages and other forms of income have continued to increase, but only because we have been taking on between $3 and $5 of new commitments in exchange for each dollar of apparent “growth” in GDP and, therefore, in incomes. A point will, inevitably, soon be reached at which we have to renege on some of these promises, either by walking away from them (‘hard default’) or by devaluing them through inflation (‘soft default’). The idea that this somehow ‘doesn’t matter’ is a fiction, because one person’s debt is another person’s asset, and because broader promises (such as pensions) form the real basis on which people plan their lives.

The deterioration in prosperity has been experienced first in the Advanced Economies, and prosperity per capita has been falling in almost all Western countries since the early 2000s. The high levels of complexity in these economies carry extensive maintenance costs, meaning that prior growth in prosperity goes into reverse at comparatively low levels of ECoE (between 3.5% and 5.0%). Less complex EM (emerging market) economies enjoy greater ECoE tolerance, but they, too, have now reached the ECoE inflexion-points (between 8% and 10%) at which prior growth in their prosperity, too, goes into reverse.

This, of course, means that the average person – first in the West, latterly in the EM countries – gets poorer. So far, at least, the rate of deterioration in top-line prosperity has been pretty gradual, but its effects on the average person are leveraged by taxation; by the priority that must be given to household essentials; and by the liens on income created by the increasing financialization of the economy.

Here’s a simple illustration of this leverage effect. A person has an income of $100. Of this, $35 goes in tax, $40 must be spent on essentials, and a further $15 goes out in interest, rent and various subscriptions and stage-payments. This leaves $10 of discretionary income for the person to spend as he or she wishes.

If this representative person’s income falls by $5, from $100 to $95, it’s mathematically true to say that he or she is worse off by ‘only’ 5%. But, because of the leverage in the equation, his or her discretionary spending capability has slumped by 50%, from $10 to $5.

This person may – and, in the real world, increasingly does – counteract this ‘discretionary squeeze’ by taking on extra debt, or by stringing out (staging) payments for purchases that hitherto would have been paid for up-front.

But all that this does is to increase the future cost of debt service and other liens on income.

Taxing times

Where fiscal issues are concerned, the prosperity problem for households is leveraged by governments’ failure to set policy based on the realities of prosperity.

In the group of sixteen Advanced Economies (AE-16) modelled by SEEDS, aggregate taxation increased by an estimated 40% in real terms between 1999 and 2019. Since recorded GDP rose by a very similar 41% over this period, the apparent incidence of taxation – measured conventionally against GDP – has been remarkably static, seldom varying much above or below 36% over the past two decades.

When we look past credit-inflated GDP to prosperity, however, the burden of tax has risen from 39% in 1999 to 49% last year.

As this pincer effect has rolled on – with taxes rising whilst prosperity erodes – relatively modest decreases in prosperity per capita have been leveraged into much more extreme falls at the level of disposable (“left in your pocket”) prosperity.

The most striking illustration of this effect is France, where prosperity per capita peaked in 2004, at €30,910. Since then, this number has declined by a comparatively modest 6.2% (€1,910) in real terms, to €29,000. But tax per capita has increased (by €3,000 per person) over that same period. Accordingly, the disposable prosperity of the average French citizen has fallen by a dramatic 34% (€4,920), from €14,700 in 2004 to just €9,570 last year. Popular anger at this state of affairs is palpable.

In few other countries has this leverage effect been quite so extreme, but declines in disposable prosperity per person have, nevertheless, been pretty striking, falling by 28.2% in Spain since 2001, by 28.0% in Britain since 2004, and by 17.4% in the United States since 2000 (see table 1).

Table 1.

Essential pressures

The adverse leveraging effect of taxation has fiscal and political implications, of course, though what interests us here is its impact on consumers.

This impact is, moreover, compounded by the growing slice of prosperity accounted for by the cost of household essentials.

SEEDS doesn’t monitor essentials spending on a country-by-country basis, but does carry out this exercise in the single instance of the United Kingdom. Over a twenty-year period ending in December 2019, average wages in Britain increased by a nominal 77%, outstripping CPI inflation (of 49%) such that, in theory, the wage-earner was better off by nearly 10% over that period.

However, the essentials index (TMUKEPI) rose by 96%, such that wages measured against household essentials decreased by almost 10% between 1999 and 2019. It’s also noteworthy that, whilst the average cost of domestic rent rose by 8% in real terms, the real cost of mortgages fell by almost 20%.

Since a sizeable part of the cost of household essentials is linked to commodities traded globally – most obviously, to foodstuffs, materials and, above all, energy – it’s a reasonable inference that these broad patterns have been replicated elsewhere in the Advanced Economies. From this, we can deduce that non-discretionary purchases, whilst they account for perhaps 37% to 40% of household expenditures, already absorb somewhere between 50% and 55% of prosperity.

If this calculation is correct, it would mean that the combined burdens of tax and household essentials are already close to, and may in a number of instances exceed, per capita prosperity. If these costs seem to remain affordable within incomes – but not within prosperity – the explanation lies in the credit effect of inflating incomes (and aggregate GDP) by purchasing “growth” using incremental debt in a ratio of 3:1.

In short, indicative numbers suggest that, over the past five or so years, the combined burdens of taxation and essentials have come to absorb all of the prosperity of the average person in a growing number of Western economies.

What this in turn means is that the average household increasingly relies on credit expansion to fund all discretionary (non-essential) purchases. In this context, ‘debt’ includes the individual’s share of all government and corporate (as well as household) borrowing. Albeit at one remove, government borrowing pays for services that would otherwise have to be funded by taxation, whilst corporate borrowing helps fund the incomes of employees, and may also serve to reduce the end-user cost of purchases.

As set out in table 2, perhaps the most extreme example of this credit effect is Ireland. Since 2004, the annual pre-tax prosperity of the average Irish citizen has decreased by €3,000 which, at 7.4% and spread over fifteen years, may seem a comparatively modest decline. Over the same period, though, his or her share of the country’s debt has soared from €82,000 to €198,000. This means that, on average, the average person’s share of debt has increased by nearly €7,700 in each of the past fifteen years.

Table 2.

Conclusions

It’s a reasonable guess that the central conclusions of this analysis will not contradict many readers’ intuitive perceptions of what has been happening.

We know that increases in income have been more than matched by increases in debt. We know that, increasingly, households are taking on financial commitments in addition to traditional obligations such as mortgages and rent. We know that taxes on the ‘typical’ household haven’t fallen to mitigate these pressures. We know that the real cost of household essentials has risen, and it will come as no great surprise that there is a corollary between rising household credit and continuing expenditures on non-essential purchases such as leisure, travel and gadgets. We also know that many other indicators of hardship chime with these observations.

In this context, it’s necessary to be clear about what we know, and what we infer. Observation over time confirms that financial ‘innovation’, and outright increases in debt and other obligations, are being used to sustain increasingly illusory ‘growth’. Our understanding of the energy basis of all economic activity should reinforce our confidence that rising ECoEs lie at the root of what began as “secular stagnation”, but has since turned into something a great deal more serious. SEEDS monitors real-terms taxation in countries accounting for about 80% of the World economy and, if we cannot calculate the costs of household essentials on a country-by-country basis, we have data sufficient for reasonable inference on this component.

We need to be somewhat nuanced in the conclusions that we draw from a diminishing, and perhaps vanishing, aggregate capability to fund discretionary purchases without resort to spiraling credit.

For one thing, inequalities between households affect the overall situation. Whilst the ‘average’ person might not be able to make discretionary purchases without using credit, there will be some below this average who already rely on credit to pay for the essentials, whilst others are in a better position, and can still make discretionary purchases without going into debt to do so. To take just one example, the interpretation presented here doesn’t imply that air travel will ‘collapse’, but does indicate that it will contract, suggesting that providers will need to carry fewer passengers, and charge them higher fares.

This said, there can be no disguising the underlying trends, which point towards overall contraction in discretionary sectors, and also highlight the vulnerability of any activity or asset which depends on income streams derived from increasingly squeezed household prosperity. Logically, the industrial landscape can be expected to rebalance away from discretionary activities, whilst a sharp correction in asset prices is likely to be led both by decay in discretionary components and by a degradation in the scale and reliability of ‘income streams’.