THE ANATOMY OF AN UNFOLDING CRISIS

Try as I might, I’ve never quite understood why T.S. Eliot picked on April as “the cruellest month”. In the northern hemisphere, winter is receding into memory by the time that April arrives, whilst spring sees nature getting back into its stride, with May and June, perhaps my favourite months, just around the corner.

April might not, then, be the cruellest month but, for me, it’s almost always the busiest. April is when we get a raft of new economic data, including final outcomes for a lot of prior year metrics, and all of this has to be incorporated into the SEEDS system.

From next month, 2022 replaces 2021 as the base year, meaning that constant financial data is expressed at 2022 values. This conversion of past numbers into their current equivalents requires application of the global GDP deflator, a series which, to the best of my knowledge, isn’t actually published anywhere. It should be noted, in passing, that there are two versions of the global deflator, depending on whether we’re converting other currencies into dollars at market or PPP (purchasing power parity) rates of exchange.

With apologies to those who already know this, SEEDS – the Surplus Energy Economics Data System – is a proprietary economic model built on the understanding that the economy is an energy system, and is not, as we are so routinely informed, entirely a matter of money.

With each year’s iteration, I try to improve the model, and the next version – ‘SEEDS 24A’, as it will be known – will incorporate more detail in two areas, which are broad financial liabilities, and the SEEDS-based RRCI (Realised Rate of Comprehensive Inflation) measure of systemic inflation.

Both are of obvious importance right now. The authorities are trying to tackle inflation without, in my opinion, having a system-wide measure of what it actually is, whilst the stability of the financial system going forward depends, not so much on ‘banks’ as such, but on the broader interconnected network of commitments. Expressed in market dollars, the aggregate of debts owed to banks by private (household and business) borrowers is just over US$90 trillion, but SEEDS estimates put global non-government liabilities at close to US$500tn.

For context, even in the wildly implausible event of all of the world’s central bankers getting together and agreeing to double their assets, the new funds thus created would cover less than 10% of broad private sector exposure.

Development of the SEEDS model began almost ten years ago, following the creation of the Surplus Energy Economics site and the publication of Life After Growth. Work on the latter persuaded me that, if the economy is indeed an energy system, there’s not much point in modelling it as though the only thing that matters in economics is money. The aim was to find out whether it was possible to model the economy on the basis of energy principles.

The strangest years

These, as you will know, have been strange years in economic and financial terms, though the period of strangeness stretches back a lot further than 2013. I hope that some reflections on this might assist our discussion of where things are likely to go next.

I like to begin the ‘narrative of the strangest years’ back in the 1990s. This, as many readers will remember, was the time when the USSR had collapsed, and satellite countries were in the process of leaving the Soviet system, variously known as COMECON and the Warsaw Pact.

For Western leaders, and indeed for their citizens, this seemed an era full of promise. The failure of Soviet collectivism appeared, by default, to have vindicated the superior merits of the market capitalist system. Western governments could anticipate a “peace dividend” from the ending of the Cold War. In the early 1990s, economies seemed set to benefit from ‘the great moderation’, a favourable combination of solid growth and low inflation. People were beginning to debate climate issues, but the threat of what was then known as “global warming” was a cloud that seemed, at that time, ‘little bigger than a man’s hand’.

If you recall this era, and concur with the foregoing description of it, you might be minded to wonder ‘where did it all go wrong?’ It’s fair to characterise our current time as one of extreme financial instability and, for millions, of worsening economic hardship. In stark contrast with the quarter-century after the Second World War, we have been witnessing a relentless widening in the gap between the wealth and incomes of the majority and those of an affluent elite.

There are all sorts of explanations for why so little of the promise of 1993 seems to have been realised in 2023, but only one interpretation really fits the facts. This interpretation is that the era of dramatic economic growth created by accessing coal, oil and natural gas has been drawing to a close.

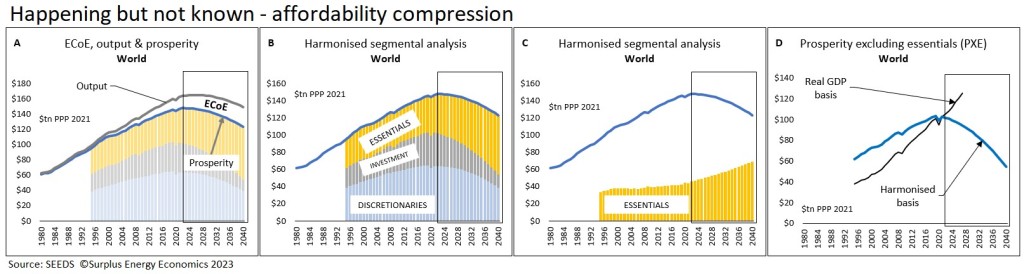

This has happened in a gradual but relentless way, spanning a quarter-century precursor zone that has seen economic deceleration give way to stagnation, and stagnation succeeded by contraction. The SEEDS model indicates that average global prosperity per person turned down after 2019, and that world aggregate prosperity may have peaked in 2022.

Comparatively few people doubt that reliance on carbon energy has, at the very least, contributed to our environmental and ecological predicament, but it seems to me that fewer still are aware of the effect that the deteriorating economics of fossil fuels have been having on the economy and the financial system.

The effect of energy deterioration can best be expressed using a metric that is known here as the Energy Cost of Energy. Whenever energy is accessed for our use, some of this energy is always consumed in the access process. Within any given quantity of available energy, a rise in ECoEs reduces the remaining ‘surplus’ energy that’s available for any other economic purpose.

Throughout the fossil fuel era, we have always used lowest-cost resources first, saving costlier alternatives for later. The resulting process of depletion has been pushing up ECoEs, and this trend started to affect economic performance during the 1990s, with global trend ECoE from all sources of energy rising from 2.9% in 1990 to 4.2% in 2000.

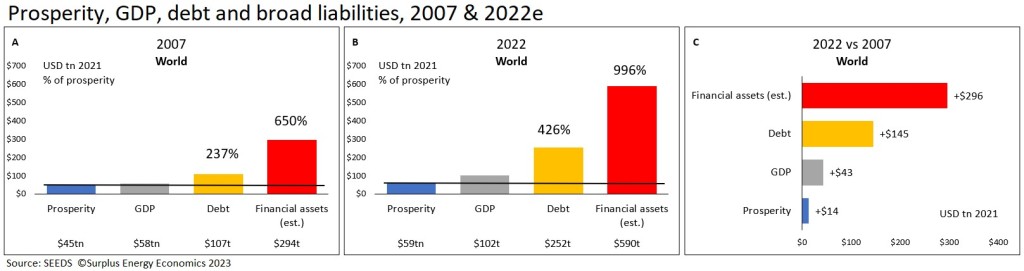

What this meant was that growth in the material economy decelerated because of a factor, ECoE, which was and is neither recognized nor accepted by conventional economic theory. Fallacious (monetary) diagnosis has led to a succession of mistaken policy responses, starting in the 1990s with ‘credit adventurism’, when it became easier to access new debt than at any time in modern history. This led to the GFC (global financial crisis) of 2008-09, to which we responded with the ‘monetary adventurism’ of QE, ZIRP and NIRP.

Parallel sequences

This much regular readers will know, but what matters here is the equation of two parallel sequences. On the one hand, growth in material prosperity has decelerated, and then stagnated, before going into reverse. On the other, our ever more fallacious attempts to fix a material problem with monetary innovation has driven a widening wedge between the ‘real’ economy of products and services and the ‘financial’ or proxy economy of money and credit.

Once this is understood, past trends start to take on the character of a logical progression, and the future becomes both clearer and more daunting. The material economy will continue to deteriorate, and the ever-widening gap between the material and the financial will fracture the latter.

To be clear, the material economy cannot be compelled to accord with the monetary one – low-cost energy can’t be loaned into existence by the banking system, or created out of the ether by central bankers. Management of the financial system involves a choice between flexing with the real economy, or holding out rigidly against it to the point of fracture.

The course of events since the GFC illustrates our collective pursuit of the wrong choice. Ultra-cheap money was adopted in extremis, and its effects were, of necessity, inflationary. Advocates of QE have long denied that money creation causes inflation, but this stance is only tenable if we disregard sharp rises in the prices of assets, and we’ve been asked to believe that low inflation is consistent with the creation of an “everything bubble” in asset markets.

Inflation made the transition from assets to consumer purchases when, during the pandemic lockdowns, QE ceased to be channelled to investors alone, but was directed to households as well. The concept of systemic inflation, measured by SEEDS as RRCI, shows that inflation has been far higher than the reported headline numbers throughout the ‘free money’ era – and, of course, if we recalibrate inflation to levels which turn out to have been higher, the extent of negativity in real interest rates becomes still more pronounced.

Central banks have received a lot of criticism for raising rates, and reversing QE into QT, in an effort to tame inflation. In fact, such criticism would be far better directed at the long period during which rates were kept below inflation. Anyone who favours market capitalism knows that this system cannot co-exist healthily with negative real rates, because capitalism absolutely requires that the investor earns positive returns on his or her capital.

The central bankers now find themselves in a situation which even they must recognise as being contradictory. On the one hand, they are reversing past money creation (QT) in an effort to bring inflation under control. On the other, they face the probability of having to create a great deal of new liquidity (QE) to backstop troubled parts of the banking and broader credit system. As we’ve seen, the assets of the entire global central banking system equate to less than 10% of world non-government financial liabilities.

Laying it on the line

The best way to try to make sense of all this is to ‘cut to the chase’, and here is how I suggest that we do so. Ultimately, the system of interconnected liabilities that we call ‘the financial system’ is viable if, and only if, household and business borrowers can honour their commitments. The banking and broader financial system wouldn’t be in trouble if, around the world, households were enjoying robust and improving prosperity, and businesses were enjoying high and rising profitability. This, of course, is the opposite of what households and businesses are experiencing now.

This means that effective interpretation requires an assessment of discretionary prosperity, meaning the resources left to consumers after the costs of necessities have been deducted from top-line prosperity. The situation on this metric is that, whilst prosperity is deteriorating, the real costs of energy-intensive necessities are rising.

This tells us two things. The first is that the affordability of discretionary products and services is declining, and the second is that the household sector will find it ever harder to ‘keep up the payments’ on everything from secured and unsecured credit to subscriptions and staged-payment purchases.

This analysis tells us that a large and growing swathe of discretionary sector businesses are under worsening pressure, and that the decline in the value of these sectors will be exacerbated by falling prices in other asset classes, most obviously commercial and residential property.

Perhaps the ultimate ‘statement of the blindingly obvious’ is that the financial system can remain viable only if (a) borrowers are able to meet their commitments, and if (b) the values of assets used as collateral for these obligations do not suffer significant impairment. Where this is not the case, the alternative outcomes are default, on the one hand, and, on the other, hyperinflationary destruction of liabilities.

Inflation has been called a “hard drug”, because it’s an easy habit for an economy to get into, and a hard habit to break. Whatever the sincerity of their current commitment to tackling the inflation caused by their earlier recklessness, central bankers are going to find it very hard indeed to say ‘no’ when pressed to create yet more new money to head off yet more crises.

These are issues to which I’m certain we’ll return. You will, I hope, allow me to say that none of these issues can be assessed effectively, let alone tackled successfully, unless we have a logical and quantified system of interpretation and projection.