WORSENING STRESSES IN AN INFLECTING ECONOMY

As almost everyone must have noticed by now, economic and broader affairs are in a strange state of uneasy limbo. The economy certainly hasn’t ‘collapsed’, as some pundits have long been predicting, but neither is it growing, in any meaningful sense.

Conditions are characterised by worsening hardship and widening inequality, and this, compounded by suspicion and mistrust, is making itself felt in increasingly fractious domestic politics. A disturbing feedback loop ties internal political discontent into the stresses of dysfunctional international relations.

There’s a growing feeling that ‘things aren’t working’, and that the continuing affluence of a minority is in striking contrast with the deteriorating economic circumstances (and worsening insecurity) of the majority.

One can almost sense a collective holding of breath as we wait to see ‘what happens next’.

I cannot escape a conviction that very few people really understand that what we’re experiencing now isn’t some kind of temporary economic stasis, but the cusp of a fundamental change for which societies are not prepared.

Accordingly, the aim here is to use the SEEDS model to make sense of this unquiet calm, and to provide some insights into what actually does ‘happen next’.

In summary, hardship and stress at the level of the micro – that is, of the household and the individual – are about to extend into disorder at the level of the macro. We’re heading very rapidly into “peak almost everything”.

The qualifying “almost” is necessary, and we need to know how we can best navigate the turbulence that is now about to commence. We need to work out which activities – which sources of income, employment, revenue, profit and value – are likely to buck the generalised trend of disorderly decline.

The two-stage inflexion

Stated at its simplest, growth in material economic prosperity has long been decelerating towards a point at which the economy as a whole inflects from expansion into contraction.

Some years ago, this decelerating rate of growth fell below the rate at which population numbers have been continuing to increase. Since 2019, the world’s average person has been getting gradually poorer, even as aggregate prosperity has carried on edging upwards.

These trends are illustrated in Fig. 1. Though aggregate material prosperity hasn’t – quite – reached its zenith (Fig. 1A), this aggregate is now growing at a rate lower than the (decelerating) pace at which the population continues to expand (1B).

Accordingly, the per capita point of inflexion (1C) occurred some years before the point of aggregate inflexion (1A).

We’re now very near indeed to the moment at which prior growth in the overall size of the economy goes into reverse. This is when the Big Numbers – the size of product and service markets, revenues and profits in the business sector, employment, resources available to governments, and the quantity of sustainable credit – all start to get smaller.

Fig. 1

The segmental progression is pictured in Fig. 1D. What comes next is a succession of peaks, including peak gadget, peak media, peak travel, peak hospitality and peak property price. We’re also likely to reach peak supportable credit and, in some cases, to discover that we’ve gone a long way past peak national cohesion.

This doesn’t mean that everything hits a peak, because generalised contraction will create opportunities for expansion in alternatives. For instance, local amenities might enjoy a revival as long-distance travel reverts to being the preserve of an affluent few. Likewise, peak property price might redress a balance of opportunity that has been loaded against the young for far too long.

The reason why

If you ask officialdom – or even if you don’t – you’re likely to be told that the economy is ticking over pretty well, and would have been doing even better if it hadn’t been for the sheer bad luck of running into a global pandemic and a European war in quick succession.

Some have alleged that these events have been engineered in order to disguise economic deterioration, and/or to cloak a grab for wealth and power by a self-serving minority. There’s no solid evidence for – or against – these claims, but the pandemic and the war have certainly thrown a mantle of confusion over what’s really been happening to the economy and the financial system.

Our best recourse is to objective analysis of economic and financial fundamentals.

Properly defined, the economy is a system for the supply of material products and services to society.

Thus seen, the economy is an energy system, not a financial one. Nothing that has any economic value at all can be provided without the use of energy. Money has no intrinsic worth, but commands value only as an “exercisable claim” on the output of the material economy. We know that the large and complex economy of today has been built on an abundance of low-cost energy sourced from oil, natural gas and coal.

The factor which does most to determine economic prosperity is the material cost of energy supply. If delivering 100 units of energy requires using the equivalent of 99 units in order to make it available, the game is scarcely worth the candle.

If, on the other hand, 100 energy units can be delivered at a cost of only 1 energy unit, this activity is immensely productive of economic value.

Energy is never ‘free’, but comes at a cost measurable in terms of the proportion of accessed energy needed to create and sustain the infrastructure required for energy supply. This cost is known here as the Energy Cost of Energy, abbreviated ECoE.

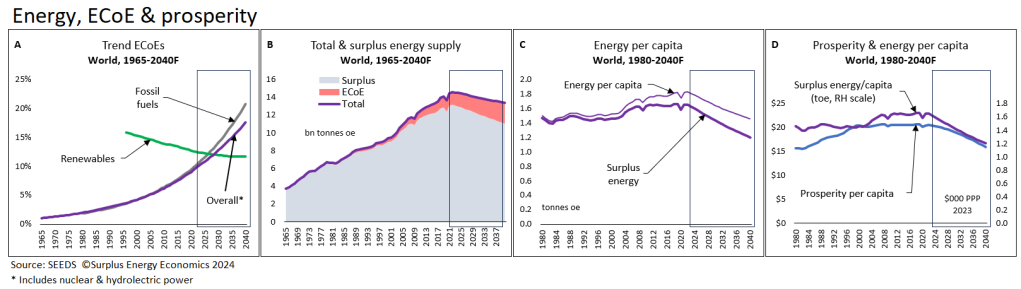

Globally, trend ECoEs reached their low point in the quarter-century after the Second World War, explaining the super-rapid economic growth enjoyed in that period.

Since then, ECoEs have trended upwards because of the depletion of fossil fuel resources. Oil, gas and coal remain abundant, but have been getting progressively costlier to access. Renewables, with their lesser energy densities, cannot take us back to a halcyon age of ultra-cheap energy.

Being unable – or unwilling – to face the implications of rising ECoEs, we’ve long been playing a game of “let’s pretend” with the economy. Because GDP is a measure of financial transactions – and not of material economic value – we can create a simulacrum of “growth” by pouring ever-increasing amounts of liquidity into the system.

Nobody needed credit deregulation, QE or sub-zero real interest rates in the 1945-70 period, because low ECoEs were driving the economy along, ‘very nicely, thank you’, without recourse to financial manipulation. Only as the economy has decelerated have we adopted various forms of monetary gimmickry in order to pretend that the illogical promise of ‘infinite economic growth on a finite planet’ remains a valid expectation.

Using the concepts of two economies, energy-determined prosperity and money as claim, SEEDS models the trajectories of financial and material economic trends. As can be seen in Fig. 2, ECoEs have been rising relentlessly, and surplus (ex-cost) energy supply has been decelerating towards contraction. Per capita surplus energy has inflected into decline, and prosperity per capita has taken on a downwards trajectory.

Fig. 2

Accompanying this, financial stresses have been worsening. Debt has massively outgrown reported GDP as credit expansion has been deployed to create purely cosmetic “growth” (Fig. 3A). It required annual borrowing of more than 11% of GDP to sustain illusory “growth” at a supposed average of 3.5% (3B) over the past twenty years. Broader liabilities have exploded (3C), and the state of disequilibrium between the financial system and the underlying material economy has become extreme (3D).

When we apply the extent of disequilibrium stress pictured in Fig. 3D to the quantum of exposure shown in Fig. 3C, the end result – a massive and disorderly financial correction – becomes a foregone conclusion.

With the exception of the stress measure illustrated in 3D, we don’t need access to the SEEDS system to work out that this ‘bigger-than-the-GFC correction’ cannot long be delayed, and will happen at the moment when the delusory promise of perpetual economic growth loses the last shreds of its credibility.

Fig. 3

Matters of coping

As we saw in Fig. 1D, what happens from here is that top-line economic output deteriorates whilst the real costs of energy-intensive necessities carry on rising. Some national equivalents of Fig 1D are shown in Fig. 4, where, in addition to the United States, China and Britain, I thought readers might be interested in how SEEDS interprets the Russian economy.

The net effect of these trends is severe compression of the affordability of discretionary (non-essential) products and services. This, it should be stressed, is already happening, though ‘the powers that be’ are, with only limited success, managing to present this as a temporary ‘cost of living crisis’ rather than as the structural phenomenon that it really is.

I’m reasonably sanguine that the public can cope – that is to say, they can survive the loss of many products and services hitherto taken for granted. After all, the term discretionary describes things that aren’t necessities. Most people didn’t have smartphones until comparatively recently, so peak smartphone – which has already happened – is manageable. We may not relish the prospect of local rather than long-distance holidays, but most of us will make the best of it. We’ll get by with less information media and less entertainment, survive the loss of social media, and come to terms with peak tech reasonably well.

Coping with peak car really involves, for many Westerners, a reversion to the one-car household that was the norm until relatively recent times, and would be made a lot easier if governments were to rediscover the merits of investing in trains, trams and buses. The over-inflation of property prices hasn’t added to the utility that people derive from having somewhere to live, and has had adverse affordability consequences both for the young and for those on low incomes.

Barry Cooper has published a valuable and timely book on the lifestyle implications of discretionary contraction, stressing that one probable consequence will be that centralised, “top-down” organisations (think multinational corporations and top-heavy government departments) will wither away, their places being taken by more localised, “bottom up” alternatives.

Unfortunately, what we might call “micro-coping” won’t translate well at the macro level. Individuals may manage without various non-essential products and services, but what happens to people employed in supplying these discretionaries, the debt and equity capital invested in them, and the contributions that discretionary sectors have hitherto made to government resources?

Because of the financial gimmickry described above, many industries have become over-capitalised, meaning that the amount of financial capital attached to any given quantity of material productive capacity has become excessive.

Businesses can be expected to adapt to contractionary forces, even where their leaders don’t, as yet, recognise where these forces are coming from. Beyond market contraction and the loss of pricing power, developing trends pose two specific challenges to business.

First, unit costs can be expected to rise as market volumes contract. This is what happens when any given amount of fixed costs has to be spread across a diminishing number of customers.

Second, the risk of loss of critical mass arises as necessary components or services cease to be available, or can only be obtained at prohibitively high cost. These are compound vulnerabilities which will exacerbate the stresses of volumetric contraction.

Within and beyond the general motif of cost reduction, businesses will be compelled to opt for simplification, which will come in two distinct forms.

The first is simplification of product, typified by a decrease in the number of different products offered to the customer. The second is simplification of process, where activities are streamlined, commonization of components is progressed, and non-vital stages in the provision of goods and services are eliminated.

The latter will involve de-layering, and this will shape the way in which job losses take place. In considering the employment consequences of discretionary contraction, we need to set aside long-ago monochrome images of despairing, hungry, cloth-capped working men queueing up for unemployment benefits.

The demand for manual labour is likely to increase as the costs of mechanisation are pushed up by tightening energy supplies. This time around, the brunt of rising unemployment will be borne by those professional, well-paid managerial and technical employees whose posts are likely to fall victim to de-layering.

All of these processes are going to change the balance of forces in civil society, such that politics becomes ever more unpredictable.

A point that cannot be emphasised too strongly is that economic deterioration, with all of its attendant stresses, is moving from the predicted to the experienced.

Some discretionary sectors are already contracting. Politics is already becoming dysfunctional. The hardship being presented officially as a temporary problem is, in reality, a foretaste of the shape of things to come – or, perhaps more aptly, the shape of things to go.

Fig. 4