A WORLD LESS PROSPEROUS

Introduction

Now that we have addressed first principles, economic output and the role of energy, we can turn our attention to prosperity. The conclusions set out here are that, whilst aggregate prosperity has gone into decline, the real costs of energy-intensive necessities will continue to increase. This creates leveraged downside in the scope for both capital investment and the affordability of discretionary (non-essential) products and services. The dynamics of prosperity are explored here by reference to the SEEDS economic model.

These conclusions do not, of course, accord with the essentially cornucopian assertions of orthodox economics, but we are in a position to observe that economics and the economy have parted company. It is suggested here that the energy-based interpretation of deteriorating prosperity is consistent with much that we can see around us.

Ultimately, the purpose of economics is – or should be – to identify, explain, calibrate and anticipate the delivery of prosperity. To do this, we need to know what prosperity actually is. Properly considered, prosperity is a material concept, consisting of the products and services that are available to society.

Prosperity isn’t ‘money’ but, rather, the things for which money can be exchanged, which is a significantly different concept. This is why orthodox economics, which concentrates on the financial and pays scant attention to the physical, struggles to interpret the meaning, quantum and processes of prosperity.

By way of analogy, we can usefully equate prosperity with households’ ‘disposable income’, which is what remains after necessary expenses have been deducted from total income. At the macroeconomic level, output is the equivalent of total income, whilst the essential expense of system operation is the Energy Cost of Energy. Therefore, we can define prosperity as output minus ECoE.

In part one of this series, we identified a direct (and remarkably invariable) relationship between underlying or ‘clean’ economic output (C-GDP) and the use of energy. Essentially, economic output rises or falls as the availability of energy increases or decreases, and this connection cannot be circumvented.

In part two, we saw how relentless rises in ECoEs can be expected to continue, whilst increasing supplier costs are likely to combine with decreasing consumer affordability to reduce the quantitative availability of energy. In short, prosperity has started to decline because of rising ECoEs, and this process may be exacerbated by a decreasing supply of primary energy.

The material and the monetary

Though the economy needs to be understood in the material terms of energy, the economic debate is customarily conducted in the language of money. The calculation of prosperity in monetary terms is possible, because we can multiply energy use (calibrated in thermal units) by the relatively invariable unit conversion ratio (stated in money) to measure and project the financial equivalent of material economic output. From this, the deduction of ECoE, as a percentage, identifies prosperity as a financial number.

This calibration of prosperity yields a wealth of useful statistics and benchmarks. We can, for instance, compare the scale of monetary transactions with prosperity to measure the degree of equilibrium (or disequilibrium) in the relationship between the ‘financial’ economy of money and credit and the ‘real’ economy of products, services and energy.

We can likewise use the relationship between the monetary and the material to measure systemic inflation, noting that prices are the financial values attached to physical products and services. These issues will be addressed later in this series.

Now, though, our interest is in the evolution of prosperity and its constituent parts. These are (a) the supply of necessities, (b) capital investment in new and replacement productive capacity, and (c) the scope for discretionary (non-essential) consumption. Critically, whilst aggregate and per capita prosperity are now contracting, the real costs of energy-intensive necessities are rising.

The bottom line is that prosperity excluding essentials – a metric abbreviated in SEEDS terminology as PXE – is in leveraged decline. This means that the affordability both of capital investment and of discretionary consumption is coming under worsening pressure. This process of affordability compression also has implications for the streams of income which flow from households to the corporate and financial sectors.

One conclusion which follows from this is that discretionary consumption will decline. Another, to be examined in the next part of this series, is that the global financial system is in very big trouble.

Past, present and future

From our energy-prosperity perspective, modern economic history fits into a logical framework. The accessing of energy from coal, petroleum and natural gas had a completely transformative effect on the economy. Advances in geographic reach, economies of scale and technology delivered falling ECoEs for most of the period in which energy use was expanding rapidly. Accordingly, for much of the industrial era, surplus – post-ECoE – energy supply increased even more rapidly than the total availability of energy itself.

Latterly, though, the depletion of fossil fuels has started pushing ECoEs back upwards, threatening to bring down the curtain on two centuries of exponential economic expansion powered by oil, gas and coal.

As the fossil fuel dynamic fades out, we can postulate three versions of the economic future. One of these, propounded by conventional economics, says that economic prosperity, being a wholly monetary phenomenon, isn’t subject to material constraints, such as those which apply to energy resources, or the limits of environmental tolerance.

This idea – that innovation in the immaterial field of monetary policy can restore expansion to the delivery of material prosperity – has been tried, and has failed spectacularly, over a quarter of a century of futile financial gimmickry.

Another claim is that technology can provide us with abundant, low-cost energy from renewables. As we saw in part two, this argument isn’t credible, because it overlooks the reality that the potential of technology is bounded by the laws of physics. Renewables cannot replicate the characteristics – including the density, portability and flexibility – of fossil fuels.

This leaves us with the third, least palatable conclusion, which is that prosperity is deteriorating because we have no complete replacement for the fading dynamic of fossil fuels. This downturn in prosperity is by no means a sudden event, but one which can be traced through a long precursor zone of deceleration, stagnation and contraction

Our understanding of prosperity as the post-ECoE value of energy enables us to calculate prosperity at any point in time, and to identify the trends which will determine prosperity in the future. For forward projection, we need to anticipate (a) the amount of energy available to the economy, (b) the financial equivalent of the output provided by this energy, and (c) the proportionate ECoE deduction that differentiates prosperity from output.

Conventional economics cannot calibrate prosperity, because it does not recognize either the energy-output linkage or the ‘first call’ on resources made by ECoE. The best that orthodox economics can do is to count – as GDP – financial transactional activity, a measure which cannot inform us about value created within the economy.

Energy-based modelling, such as the proprietary SEEDS system used here, can calculate prosperity, which can then be used, not just as an analytical and predictive tool, but as a benchmark for referencing numerous other calculations and ratios.

The big picture

Naturally, our first concern here is with the quantum of prosperity itself, stated either as an aggregate or in per capita terms. But we also need to explore a number of other issues which we can access with prosperity itself established.

How, over time, is prosperity allocated between the provision of essentials, the financing of capital investment and the provision of discretionary (non-essential) products and services? Looking ahead to the next instalment of The Surplus Energy Economy, what is the relationship between the ‘real’ economy of prosperity and the ‘financial’ economy of monetary claims on that economy? And what can this relationship between the material and the monetary tell us about inflation?

The outlook for prosperity itself is stark. Until recently, the global economy has carried on expanding, but at a decelerating rate. Now, prior growth in prosperity has gone into reverse. At the same time, the costs of energy-intensive necessities are increasing, not just as absolutes, but as a proportion of available resources. The resulting affordability compression undermines the scope both for discretionary consumption and for capital investment.

As we shall see in part four, there is a severe disequilibrium between the material and the monetary economies, meaning that enormous ‘value destruction’ has become unavoidable. This points towards disorderly degradation within the interconnected liabilities which are the ‘money as claim’ basis of the financial system.

The basics, at the aggregate level and in per capita terms, are summarised in Fig. 8. Between 2021 and 2040, both energy consumption and underlying output (C-GDP) are projected to decline by -8%. With ECoE likely to rise from 9.4% in 2021 to over 17% by 2040, the fall in aggregate prosperity is leveraged from -8% to -16%. Further (though decelerating) increases in global population numbers indicate that prosperity per capita is likely to be 27% lower in 2040 than it was in 2021.

Fig. 8

It will be obvious that these projections differ starkly from orthodox forecasts, which are rooted in the proposition that financial management can enable economic output to increase in perpetuity, without encountering any material constraints imposed by the finite characteristics of energy, other resources or the environment.

Within our energy-based interpretation we can conclude, not just that output and prosperity have turned downwards, but also that much prior “growth” in reported economic output has been the cosmetic product, not just of disregarding ECoEs, but also of creating transactional activity by the injection of ever-growing quantities of cheap credit and cheaper money into the system.

With these parameters established, our interest now turns to the meaning of prosperity decline. First, though, we need to note that nothing that is happening now has occurred without prior warning.

Indications and warnings

Prior notice of impending economic contraction has taken two forms. One of these is modelled prediction, and the other is the action that has been taken by the authorities.

Where prediction is concerned, pride of place must be given to The Limits to Growth (LtG), published back in 1972. Using the World3 system dynamics model, LtG examined the relationships between critical metrics including population numbers, industrial output, food production, the supply of raw materials and what was then called “pollution”. It concluded that economic growth must come to an end, with indicators pointing towards the early twenty-first century as the period in which this was likely to happen.

The LtG projections have proved remarkably prescient, as has been demonstrated by subsequent re-examinations of the calculations. These warnings were disregarded, not because they were wrong, but because they were inconvenient.

Policy actions and outcomes over the past quarter-century provide equally compelling proof of the gradual onset of economic contraction. We have been applying financial gimmickry in a series of futile efforts to restore economic growth, something which we would not have done had the economy itself been continuing to deliver expansion.

To be clear about this, nobody introduced credit expansion, QE, ZIRP, NIRP or any other expedient for the fun of it, or ‘to see what might happen’. These and other innovations were adopted only because the economy and the financial system were in trouble. Where economic deterioration is concerned, this is ‘the evidence of behaviour’.

In the 1990s, observers identified a phenomenon which they labelled “secular stagnation”, meaning a non-cyclical deterioration in the rate of economic expansion. Because of the convention which insists that all economic issues can be explained in terms of money alone, they did not trace this to its source, which was the relentless rise in trend ECoEs.

Proceeding instead from the mistaken premise that money explains everything in economics, they sought to ‘fix’ this problem with monetary tools. Their solution, amenable to the deregulatory preferences of the day, was to ‘liberalise’ the supply of credit, making debt easier to access than it had ever been before.

This initial policy approach is known here as “credit adventurism”, and there was a period in which it appeared to be working, with global real GDP increasing by 50% between 1997 and 2007. This, though, was accompanied by a 77% real-terms increase in debt, with each $1 of reported “growth” accompanied by $2.40 of net new debt. Stripping out this ‘credit effect’ reveals that, within the total “growth” recorded in this period, more than half (54%) was the purely cosmetic, transactional effect of pouring abundant new credit into the system.

These strains, combined with hazardous lending practices and inadequate regulation, led directly to the global financial crisis (GFC) of 2008-09. Rather than accepting the failure of “credit adventurism”, though, we opted to compound it with “monetary adventurism”. ZIRP, NIRP and QE were used, supposedly on a “temporary” and “emergency” basis, to reduce the cost of capital to negative real levels, where it has remained ever since.

In the process, we abrogated the basic principles of market capitalism, which are that (a) value and risk must be priced by markets free from undue interference, and that (b) investors must earn positive real returns on their capital.

The results of this second-phase gimmickry have been completely predictable although, this time around, the numbers have been even worse. Between 2007 and pre-pandemic 2019, real GDP expanded by 48%, but debt increased by 81%. Each dollar of reported growth now required the creation of more than $3 of net new debt. Fully 64% of all the “growth” recorded between 2007 and 2019 was cosmetic.

The way in which historians of the future are likely to describe this period seems clear – they will recognize that prosperity was trending downwards, and conclude that we were prepared to try anything and everything, however illogical and however dangerous, rather than come to terms with this unpalatable reality. We can best describe the period since the second half of the 1990s as a quarter-century “precursor zone” to the involuntary economic de-growth that has now arrived.

During this long period, economic output and prosperity have followed a process of deceleration, stagnation and contraction. In denying this, and trying to fix a material problem with financial tools, we have created an asset bubble that is destined to burst, and a vast interconnected network of liabilities that cannot possibly be honoured ‘for value’ by a contracting material economy.

Observing prosperity contraction

As we have seen, a deteriorating energy dynamic has put prior growth in economic prosperity into reverse. This process will have to go a great deal further, and continue for a lot longer, before there will be any chance of this reality gaining widespread acceptance. We cannot expect recognition to arrive through persuasion, however logical and evidential such persuasion may be. For those of us who understand the dynamic that has put prior growth in prosperity into reverse, our best recourse is to knowledge, concentrating on the ‘why?’ and ‘what?’ of prosperity contraction.

As we have also seen, the primary factor driving prosperity downwards is the relentless rise in ECoEs. As ECoEs rise, energy availability becomes increasingly problematic, and the post-cost value of remaining energy supply decreases.

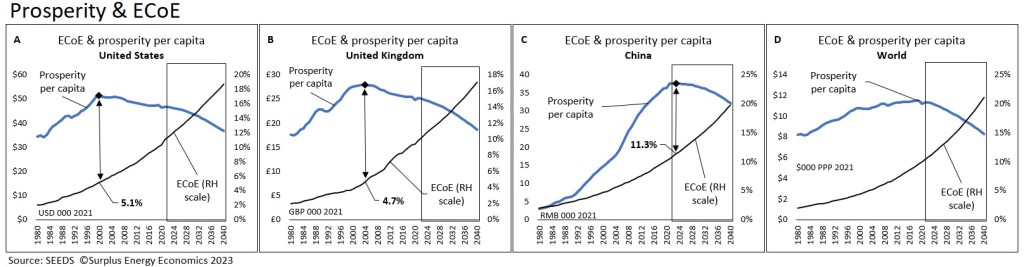

The way in which this works shows stark regional differences, and these are illustrated in Fig. 9, where trends in real prosperity per capita are compared with ECoEs.

In the United States, prosperity per person turned down after 2000, with the same thing happening in Britain in 2004. But Chinese prosperity per capita has carried on improving, and is only now drawing close to its point of reversal.

These inflexion-points have occurred at very different levels of ECoE. When prosperity turned down in America in 2000, national trend ECoE was 5.1%, and the British equivalent in 2004 was 4.7%. Almost all Western economies experienced prosperity reversal in the years before 2008, when global ECoEs were still below 6%. Yet if, as is now projected by SEEDS, prosperity per person in China turns down in 2023, it is likely to have happened at an ECoE above 11%.

The cause of these differences can be traced to comparative complexity. The high levels of complexity in the Advanced Economies result in upkeep expenses which increase these economies’ sensitivities to rising ECoEs. In almost all Western countries, prosperity per capita had turned down even before the 2008-09 GFC.

Less complex EM (emerging market) economies, which have lower systemic maintenance costs, are better equipped to cope with rising ECoEs. Only in recent years, at higher levels of ECoE, have EM countries started to encounter the process of prosperity reversal long ago experienced in the West. Whilst Mexican prosperity per capita inflected in 2007, and the same thing happened in South Africa in 2008, prosperity did not turn down in Brazil until 2013, followed by India and Indonesia in 2019, Turkey in 2021 and South Korea in 2022. One of the last countries to encounter this turning-point might be Russia where, all other things being equal, prosperity per person could carry on increasing until 2025.

The global result has been a long plateau in prosperity per capita, as shown in Fig. 9D. This plateau has been caused by continuing progress in EM countries offsetting deterioration in the West.

We do not need to conclude, as many have, that some form of greater national ‘vibrancy’ explains the superior economic performance of countries such as China, India, Russia and Brazil in comparison with supposedly ‘staid’ Western economies. Rather, the explanation lies in the varying impact of rising ECoEs in countries with differing levels of complexity.

As a rule-of-thumb, we can state that Advanced Economies need ECoEs of less than 5% if they are to grow their prosperity, whereas EM countries can carry on doing so until ECoEs are between about 8% and 10%.

Fig. 9

Essentials – the leveraged equation

Based on SEEDS analysis, aggregate global prosperity is likely to have peaked last year, at $88tn and will, by 2030, have fallen by a seemingly-modest 3%, though even this will equate to a 10% decrease in per capita terms. By 2040, aggregate prosperity is expected to have fallen by 16%, and its per capita equivalent by 27%, from their 2022 levels.

These references, though, are to top-line prosperity, whether expressed per capita or in aggregate. Our need now is to calculate what deteriorating prosperity is likely to mean in terms both of economic activities and of lived experience.

What we are watching is a two-stage process in which, just as top-line prosperity is falling, the real costs of energy-intensive necessities are rising. This creates a process of affordability compression which has far-reaching implications.

Conventional economic presentation divides the economy into sectors, which are households, government and business, with the latter sometimes further subdivided into financials (such as banks and insurers) and private non-financial corporations (PNFCs).

The SEEDS preference, on the other hand, is for functional segments, which are the supply of essentials, capital investment in new and replacement productive capacity, and discretionary (non-essential) consumption.

There is no hard-and-fast definition of ‘essential’ which, in any case, varies between countries and over time. Many products and services now deemed essential were regarded as ‘luxuries’ (discretionaries) in earlier times. This process of definitional change can be expected to continue, though this time in the opposite direction, with some things now seen as essential once again becoming discretionaries as prosperity contracts.

SEEDS analysis of ‘essentials’ fall into two categories. The first of these is public services provided by the state. This is not to assert that every service made available by government is indispensable, but these services rank as ‘essential’ because the individual has no discretion – choice – about paying for them. This definition does not embrace all public spending, because it excludes those transfers (such as pensions and welfare benefits) made between groups. The other category of essentials is household necessities.

It will be apparent that, in definitional as well as quantitative terms, the ‘essentials’ numbers used by SEEDS are estimates. The composition of ‘essentials’ varies between countries, not least because services provided by the government in some states are paid for privately in others.

Going forward, the general picture seems to be that public service costs are growing by about 1.5% annually on a per capita basis, with the costs of household necessities increasing by about 2.0%. Both are ‘real’ measurements, meaning that they are increases in excess of broad inflation. Rises in the real costs of necessities clearly over-shot this trend in 2022, because of sharp increases in the costs of energy and food. Inflation itself is an issue that will be examined later in this project.

Harmonised analysis

As we have seen, reported GDP is a misleading metric, capable of being inflated artificially by precisely the kind of credit expansion that we have been experiencing over a very long period. Even so, latest-year GDP is a number in common use, and it’s helpful, for purposes of comparison, to base some SEEDS projections on this number. In SEEDS terminology, this is known as harmonised analysis.

This process is illustrated in Fig. 10, which presents global GDP on three different formats. The first of these is nominal, otherwise called ‘current money’, in which GDP is shown without adjustment for inflation. On this basis, global GDP rose from $53tn in 2001 to $147tn in 2021, an increase of 177% (see Fig. 10A).

It is essential, of course, that adjustment is applied for changes in the general level of prices. In conventional economics, this is undertaken by applying the broad-basis GDP deflator to convert historic numbers into their current-value equivalents. With 2021 set as 100, the global GDP deflator for 2001 is 72.6 and, on this basis, GDP for that year is revised upwards, by 100/72.6, from $53tn at current prices to $73tn at 2021 values. On this basis, ‘real’ growth in GDP was 101% between these years (Fig. 10B).

As we have seen, though, this trend in recorded real GDP does not reflect the progression of prosperity over time – GDP has been inflated artificially through credit expansion, and no allowance has been made for ECoE.

Using 2021 GDP as a basis for comparative forecasting does not remotely mean that we should accept the misleading past trends presented by conventional data. SEEDS analysis informs us that prosperity increased by only 32%, rather than the reported 101%, between 2001 and 2021. The application of this pattern to prior years gives us a ‘harmonised’ trajectory, whereby 2021-equivalent output in 2001 wasn’t $73tn, but $111tn. This is shown in Fig. 10C.

As Fig. 10D illustrates, underlying growth (shown in red) has been far lower than the reported equivalent over an extended period, and has now turned negative.

Fig. 10

Segmental interpretation

Restating past trends in economic prosperity has two purposes, both of which are extremely important. First, it provides a historical context for forward projections. Second, it gives us an ability to interpret segmental trends as they affect essentials, capital investment and discretionary consumption. This is illustrated in Fig. 11, where the first three charts correspond to their ‘nominal’, ‘real’ and ‘harmonised’ equivalents in Fig. 10.

Nominal progressions (Fig. 11A) are of no great significance, as it’s generally recognised that allowance has to be made for inflation. But the inadequacy of past restatement on the basis of ‘real’ GDP is of huge importance. Seen in this conventional way, the rate of increase in the real costs of essentials has been more than matched by growth in top-line output, enabling both capital investment and the affordability of discretionaries to expand. Continuation of these positive trends – particularly in discretionary sectors – is the default assumption for anyone, in business or government, who makes plans on the basis of economic orthodoxy.

Quite how mistaken such assumptions are is apparent in Fig. 11C, which sets out segmental progressions and projections on the basis of output harmonised to trends in prosperity. As prosperity deteriorates in a way that orthodox interpretation cannot project – and as the real costs of essentials continue to rise – the affordability both of capital investment and of discretionary consumption are set to decline markedly.

It’s worthwhile pausing to contemplate what this means. Anyone involved in capital investment, or in the supply of discretionary products and services to consumers, is likely to be planning in the mistaken belief that these activities can be relied upon to expand. He or she is being misled by fallacious interpretations of the past into unrealistic expectations for the future.

This issue of mistaken expectation is captured in the metric PXE. Meaning prosperity excluding essentials, PXE is a measure of the past and projected combined affordability of capital investment and non-essential consumption.

In Fig. 11D, PXE is shown in two formats. The harmonised, SEEDS-interpreted history and outlook for PXE is shown in blue, and the equivalent based on orthodox economics is shown in black.

Anyone planning on the conventional basis is using past growth (most of which didn’t actually happen) to project forward expansion (which is an unrealistic expectation). By comparing these lines, we can see the extent of mistaken expectation informing decisions in capital investment and in discretionary sectors.

We don’t, in fact, need to rely on projection, in that ‘affordability compression’ has already become a reality. But the fundamental significance of this process lies in its implications for the financial system, something which will be examined in the next part of this series.

In essence, affordability compression doesn’t only mean that consumers are going to have to adjust to a decreasing ability to make non-essential purchases. It also means that households will find it an ever-greater struggle to ‘keep up the payments’ on everything from secured and unsecured credit to staged-payment purchases and subscriptions.

Readers can reach their own conclusions on what this means for individual sectors and for the broad shape of the economy. Our interest turns next to what declining prosperity and worsening affordability compression are likely to mean for the financial system.

Fig. 11

Thank you Dr. Morgan for another eye opener. I am, as always, sharing this around in the hope that a few with start to question the orthodox view of economics.

You are most welcome. Part 4 (finance) should be published soon.

A Few Thoughts

*The future our children and grandchildren experience will be determined by how the political leaders and the public which elects them behave in the next 5 years. If the future is nuclear powered hypersonic missiles, fusion weapons, and resource wars, then the future looks grim indeed.

*The comment that Russia can continue to grow for a number of years, based on their resource base, explains a lot about the relationship between the NATO countries and Russia. It also explains why Putin keeps talkings about more international trade and arms limitations agreements, when nobody in NATO wants to even consider such things.

*If, somehow, the world avoids complete destruction, then many different possibilities emerge. There are many, many examples in history of civilizations which lived with much lower free energy than the OECD countries enjoy today. If we play our cards right, we might even put some water back into the soil to enable food production and drinking water storage, which has a cooling effect on the planet.

*Destruction in some sectors may make the whole enterprise healthier. The collapse of the energy intensive processed food industry is an example. And if people walk more carrying weight, they will avoid much chronic disease as they age.

I could speculate about what I think is the most likely path or paths, but you can do that at least as well as I could do it.

Don Stewart

Thanks, next post will mean time to place your bets

I’d say a lot of them can be placed now……………

Only if you have sufficient ‘discretionary income’ 🤩

Chiefs or Eagles?

I will be watching the big Sportsball game tonight by good olde over the air broadcast. I bought a $30 indoor antenna and it works fairly well, better after dark it seems, if anyone who is science-y can explain why.

last year I adjusted how I expend my PXE by “cutting the cord” on 1,000+ station satellite TV. The last price increase pushed it to almost $2,000 per year, that’s crayzee.

good to see PXE back in focus here.

I want my, I want my PXE.

Letting subscriptions lapse is one of the two things that are going to change the media – the other is a decline in ad revenues. These trends, I think, are self-evident in the trend in PXE. It won’t only affect the media, of course – this de-financialization is also going to hit “tech” in a big way.

In most airports these days, passengers don’t walk straight from check-in to departure lounge to boarding gate, but are steered through shops en route. This is an example of financialization, in this case of the walk from check-in to aircraft (where your choice of seat has often been financialized as well). This will unwind as PXE decreases, with both foot-fall and spend-per-person decreasing. I mention this as a minor, but interesting, example of looming de-financialization.

I’m glad you find PXE helpful, as I think it’s important (and unknown to orthodox economics and business planning).

Thank you Tim, for another seriously insightful post. We – as in the world – greatly needs your voice on this, and I too am sharing it around. Unsurprisingly, I also have some questions and comments:

Wellbeing and prosperity: you don’t mention the relationship between these important facets of life, and I trust coming posts will delve into the difference, as they are not the same.

An important, if more fine-grained, issue is how affordability compression will end up being distribute across different levels of society. It is hard to avoid the sense that it will adversely affect less-wealthy sectors of society in a hugely disproportionate way, partly because they are intrinsically more vulnerable, partly because the more wealthy are better placed to protect their own interests (that is not intended to be a left vs right comparison but more a reflection on human nature – and especially in disconnected societies such as are now the norm).

Your insights under Observing prosperity contraction are fascinating, and especially those on the relative complexities of societies vis a vis when they experience downturns.

I would value your further comments on the relationships between the four % ECoEs you reference (three around 5% and China over 11%) and “EROIsoc” as has been explored by the likes of Hall and Lambert. Am I somewhere near the mark in inferring that, with EROI=approx. 1/ECoE, the 5% figures reflect an EROIsoc of around 20 for Western societies? (As I noted in a recent comment on your posts I see this as a fundamental part of the equation as to how well we can live with rising ECoE.)

And finally, a further comment/question on complexity, as I think it is a concept that helps account for other areas where society struggles. It seems that much of the world, and certainly New Zealand, is struggling to maintain a workforce capable of delivering the core services society requires (e.g. we have a chronic shortage of people with “staple” skills such as nurses, bus drivers, firemen, doctors, truck drivers, farm workers…) and, as I also read for much of the rest of the world, we also have an endemic housing affordability crisis.

While many of these problems are undoubtedly symptoms of the rising ECoE and “economy vs economic disconnect” that you discuss, I also see increased complexity per se as a contributing factor to the above problems. E.g. I am familiar with our building industry, and obtaining building consents now takes some four times the architectural and checking inputs required say 40 years ago. Not only is this a symptom of complexity, but a consent then also incurs greater monetary and labour inputs to achieve (and is generally coupled with a more complex and expensive construction process). This in turn means a greater portion of society’s labour force is needed to build, say “a house,” thereby diminishing the ability of society to house itself. It’s not hard to apply the same principle to other fields.

It seems there is likely a somewhat dynamic “balance” between the complexity of society and its ability to do the things it needs to do. Your thoughts on how this ties in with the dynamics of ECoE would be fascinating

Thanks Lindsay.

Wellbeing and prosperity are indeed different, and the focus here has necessarily been on the latter. That will be the case again in part 4 (finance), but we can turn to broader issues in part 5, provisionally entitled “what next?” The aim with this series (parts 1 to 4) has been a comprehensive assessment of energy, the economy and finance.

The point about complexity and ECoE-tolerance seems to me very important. I have never been comfortable with the idea that the superior performance of EM economies can be ascribed to the greater ‘vibrancy’ (or whatever) of the people of China, India and so on – lesser complexity, and hence lower maintenance costs, seems a better explanation, and doesn’t involve stereotyping. SEEDS modelling makes the inverse relationship between complexity and ECoE-tolerance very clear, I think.

In past discussions we have looked at the “de-complexification” that is likely to accompany economic contraction, and it might be an idea to revisit my “taxonomy of de-growth”, which concentrates mainly on how businesses will adapt to survive in a shrinking economy.

Dr Morgan,

You very rightly point out that SEEDS must track “(a) the amount of energy available to the economy, (b) the financial equivalent of the output provided by this energy, and (c) the proportionate ECoE deduction that differentiates prosperity from output”.

If it is not already included in the SEEDS framework, another energy metric that is very important to prosperity calculation is related to maintenance of capital assets. Maintenance energy must be deducted from the surplus available to society because it simply preserves what already exists, contributing no new service or functionality. This energy cost is significant and increases in lockstep with any net increase in physical capital.

As Tainter pointed out in Collapse of Complex Societies, increasing complexity, much of which is increased capital base, presents increasing costs of maintenance and operation. Eventually these marginal costs exceed the marginal benefit from increased complexity.

There are numerous examples of maintenance costs, but one of the simplest is the repair of tarmac road surfaces. Even if the materials of the road surface can be removed and recycled, the energy required to heat the asphalt and operate the machinery needed for resurfacing is more than a minimal fraction of the energy required to build the road in the first place.

You have pointed out that emerging markets can tolerate higher ECOE because they have “lower systemic maintenance costs”, so you are well aware of the issue of maintenance costs, but I am not aware of how you incorporate these costs into SEEDS (if indeed you have).

I think this aspect of societal energy balance will become more important because just as increased Capex commits society to increased energy expenditure for maintenance, abandonment of existing capital (or partial abandonment through deferred maintenance) can free up energy for other uses.

This means that another effect of declining net per capita energy will be the accelerating decay of capital assets. Roads will go to potholes, paint will peel off buildings (or buildings will be abandoned entirely) and we will see a general crumbling of physical infrastructure. I expect that less essential infrastructure will go first. Airports will be abandoned before water systems, but capital decay will become a larger and larger component of decreased prosperity.

Joe:

The primary aim with SEEDS has been to model the connections between energy use, economic output and ECoE. The core equations are energy conversion to economic output, and the ECoE deduction betwen output and prosperity.

I’m aware of the capital maintenance issue, and I think it fits in at the point where complexity and ECoE-tolerance intersect (which is why prosperity per capita turned down at a far lower ECoE in the US than in China). I would point you towards the harmonised analysis section in this latest instalment. Instead of dividing the economy into the orthodox “sectors” of households, government and business, SEEDS references functional “segments”, which are essentials, capital investment and discretionary consumption. I believe that some connections remain to be made, but at least capital investment has an identified place in our analysis.

You’ll know that classical economics has tried to ascribe growth, either to capital or to labour, eventually concluding that these together only account for c40% of growth, and then ascribing the remaining 60% to the rather nebulous general factor productivity.

I like to think that, with energy-output conversion and ECoE, followed by harmonised segmental analysis, we have gone a long way along a different analytical pathway, but there’s undoubtedly a lot further to travel.

My earlier post

hinted that there are many choices about how the world might be reconstructed after the collapse or sharp decline in the current regime. Charles Hugh Smith, in his note to subscribers, notes that the enormous bubble in monetary wealth among the “super rich” and those who are only “really rich” has created a huge amount of money looking for a place to get parked. The result is that prices of things like houses get inflated far beyond what an ordinary person could ever afford. The rich have ruined neighborhoods and cities parking their money. Charles’ solution:

“The best thing that could happen would be a catastrophic and permanent collapse of global financial wealth, on the order of an 80% decline.”

One doesn’t have to agree with his arithmetic to get the point that the Economists have so thoroughly screwed up capitalism that there may be no way to escape without a severe collapse or decline.

Don Stewart

My first thought is that we no longer have capitalism. The capitalist system requires two things. The first is that markets, though regulated to combat malpractice, are free to perform the functions of price discovery and the pricing of risk. The second is that investors must earn positive real returns on their capital. Neither predicate now applies.

Recent events have demonstrated the fallacy of inflation-free capital appreciation through monetary policy. The SEEDS measure of comprehensive inflation (RRCI) shows that systemic inflation has long been a lot higher than the headline numbers.

Asset prices are destined to fall a very long way from where they are now. Some sectors are likely to implode. Asset prices are a function of (a) what we think the future will be like, and (b) the cost of obtaining capital to place our bets about the future.

The former, which I call “futurity”, is subject to negative change as the deterioration in economic performance becomes apparent.

The latter is being pushed up because, even within the official (and misleading) calibrations of inflation, a clear connection is being demonstrated between inflationary risk and loose monetary policy.

Does the capitalist system necessarily require investors to earn positive returns on their capital? If so, and we aren’t living under capitalism, what system are we living under?

There are two ways to earn a return on equity investment – income returns and capital appreciation – but these operate in quite different ways at the aggregate level. If someone invests $1000 and receives a $50 cash dividend, that’s a return of 5%, or 3% real if inflation is 2%. In aggregate, this flows to all investors as $Xbn in cash paid to them by quoted companies. It is sourced from cash returns on those companies’ assets.

Alternatively, a stock bought for $1000 rises to $1050, giving the same return. But this cannot be monetized as a systemic gain – if all investors were to try to sell, it would be impossible, by definition. So, at the aggregate level these a purely notional returns. They can be created by ultra-loose monetary policies, but cannot be monetized.

There are many terms for the current system, ‘post-capitalist’ being one. It comes to an end when (a) enough investors realise its time is up, and rush for the exits, or (b) when the ultra-loose monetary policy that created the bubble becomes unsustainable.

I think it is the Wile Coyote system…to be brief.

Don Stewart

That’s as good a definition as any!

global corporatocracy.

Thanks again Tim, for an in-depth detailed explanation. I particularly liked Fig 10 in your graphs and the comparisons with classical economic indicators. If I hadn’t grasped that the GDP figures thrown around by mainstream media news headlines was grossly inaccurate and highly inflated before, I certainly do now!

I had always thought GDP was a poor indicator of ‘prosperity’, because it included activity in what I thought of as high-externality “use-once-throw-away” types of industries such as producing useless household gadgets collecting in ‘junk’ drawers and cupboards, children’s toys (particularly cheap e-toys), cosmetics, fast-foods etc that really have little or no real ‘value’, but ending up in landfill. Along with deliberate ‘planned obsolescence’ in production. My own personal example, was having to replace a 20-year old dishwasher that worked perfectly all that time. According to my plumber, apparently at some point in that 20 years, they replaced a lot of the steel components with plastic ones with shorter lifespans.

But these sorts of industries also create jobs, and there is another ‘rub’, affecting discretionary income in the aggregate if they were removed as ‘non-essential’. Perhaps there should be planning for future workforces to be transitioned to other sectors, such as infrastructure repair and maintenance, or natural /climate disaster clean-ups, environmental mitigation projects, community health and welfare etc. However, such activities don’t provide returns on capital, don’t produce anything which can be sold for a profit, and hence usually paid for by the state from tax revenue, which they can no longer generate.

However I had not known, that the classical GDP also included financial transactions until I read here – and I am so looking forward to the next one in this series.

The 90s were an eye-opener for me, working in govt in “selling off the farm” (including selling off gold reserves) as previous publicly owned services were sold to the ‘private sector’ (often for bargain basement prices too) because of course, classical economics tells us the ‘free’ market (but never a ‘fair’ market!) and healthy corporate competition with little regulation, can always do it cheaper, and invest more capital in technical innovations etc, we all the know the drill.

Many years ago I recall an idea being touted of taxing 1c for every $1,000 or $10,000 or whatever, of financial transactions, as an alternative to applying VATs, GSTs etc. With gazillions being transacted every minute, it would end up being a sizeable return for governments to help structural deficits, and would have been technically easier too. Having spent most of my working life in public service sectors, my financial exercises were more about trying to find ways to provide public sector services and social programs with less every year. Depending on which political stripe of government was in power, how much “efficiency dividend” we could squeeze from our modelling, or in other words – how much cost-cutting, program cutting, staff cutting etc had to be done due to less tax revenue coming in. And with discretionary spending falling, this means more and more folks, will not be paying into GST either, reducing further revenue for govt services.

Thanks. If memory serves, the idea of taxing financial transactions is known as a “Tobin tax”.

As discretionaries contract, a great deal of labour will need to be re-directed, reversing the previous trend where cheap energy drove the replacement of labour with machines.

On the point about dishwashers, economic contraction will change business models, not least by changing customer priorities. Consumers can be expected to prioritise longevity, and simplicity of maintenance and repair, over “bells and whistles”. The businesses which will survive and thrive will be those which focus on these changing priorities.

@Dr Tim

“On the point about dishwashers, economic contraction will change business models, not least by changing customer priorities. Consumers can be expected to prioritise longevity, and simplicity of maintenance and repair, over “bells and whistles”. The businesses which will survive and thrive will be those which focus on these changing priorities.”

Or people will just wash the dishes by hand in the kitchen sink!🤣

That too, of course!

@Dr Tim

Joking aside, it’s has been strange to see dish washers go from luxury items 20 years ago to standard today. Everyone I know (except for me) now has one. Never really understood the need for one. Never felt that washing dishes an onerous task.

The two “white goods ” I would most miss are a fridge freezer and the washing machine (clothes).

But I guess people coped without them in the past.

Washing dishes

I have a dish-washer, which I haven’t used in at least 10 years. I consider getting my hands in warm, soapy water a luxury. (Try to fit that into SEEDS). As for clothes, I do like the machines. When I was 5 years old (77 years ago), I accompanied my mother to what the called the “washateria”. There were 4 tubs with water and a hand wringer. One stirred the clothes with a stick. A few days ago I saw a movie from around 1960 of some Northern European cave explorers going to far off southern Italy. As the military helicopter circled overhead, we can see the village women down at the stream washing their clothes. A combination of an essential task and a social gathering.

I remember as a small child helping my mum do washing in the “copper”, a big drum outside the house backing onto the rear of the kitchen woodfire, with its own fireplace underneath and a handwringer. Also attached to raised rain water tanks, one tank kept warm from the kitchen fire for the tacked on shed with a big family bathtub.

I remember outhouses too, but not with any nostalgic fondness.

I think the handwringer was known in England as a ‘mangle’ (cue gag from Derek & Clive).

I don’t remember these same things from childhood, but I do remember vans – grocer and greengrocer – doing rounds along our rural road, stopping every few houses and people would come out and buy from them. I also remember my local small town proudly opening its new state-of-the-art swimming pool. That’s since closed, I believe (local authority couldn’t afford the maintenance). That same town had lots of nice little shops, demolished to build a Shopping Centre.

@John Adams

The same could be said for microwave ovens and TV sets, or even hot showers and indoor toilets! 🙂

I installed my first dishwasher when I was a working sole parent of 3 tween/teens. It helped to ease a lot of emotional/psychological stress 🙂

I even gave up smoking to pay for it 🙂

@rainsinger

I guess dishwashers and microwaves have appeared in my lifetime, that’s why I find them strange. I can remember a life without them and have never owned either. People must find them useful though, or else there wouldn’t be so many.

Indoor toilets and hot showers were around before my birth, so seem “normal” though my parents must have found them as game changers.

The reversal of this whole process is going to be interesting. Even indoor toilets may become obsolete if the sewer and water systems can not be maintained?

This article is a must-read, whatever your view of the politics of what happened to the UK in September 2022. It is as relevant to those outside the UK as it is to those in Britain. The article gives a commendably clear explanation of the mechanics of the LDI schemes which threatened to blow up British pension funds at that time. There is no reason to suppose that this is confined to the UK.

I’ll cite two paragraphs which are particularly important:

“Liabilities short and assets long, with steep levels of leverage – particularly in an often financially incompetent industry such as pensions – always ends in tears once rates start rising. It’s important to note, however, that leveraging of pension funds is a new folly. That meant new money managers were newly credulous. Salesmen flourished. Rapidly, all over the world, these funds burgeoned – and nowhere more so than in the UK.”

“To use an illustrative example, imagine a pension fund that starts off with £1bn in assets (in this case gilts) and leverages these up five times. It now owes £5bn, and owns £6bn in gilts. If rates go up, causing the gilts to fall by 10% in value, the bank has lost £600m overall. The covenant is triggered. The covenanted bonds, valued at £5.4bn, are sold into the market. £5 billion goes in repayment to the lender and £400 million goes back to the LDI fund, which now only has £400m of the £1bn it started with. The fund has lost 60% of its value, and its members are facing a world of pain, which may include never getting their full pension or, for some unfortunate souls, almost anything at all (the pension insolvency laws are hard on those who have not yet retired). “

Isn’t this a liquidity/solvency issue? The bonds are still worth face amount at a given time in the future; selling them for liquidity leads to the loss. Being a bank and wanting to use them as collateral on a loan which in return requires payments is the same thing; when not if one will be paid.

Housing is similar, prices vary but utility to a tenant/owner is more or less constant, the roof keeps water off one’s head.

Squeezing every bit of “income” out of these transactions is overhead in search of liquidity. Shut down the entire process/organization doing this and there should be a net gain to holders/payers of said bonds. But, there will be liquidity problems, which are due to the underlying low return of real assets which is a rate problem, not a total return issue.

Liquidity appears to be a way to mask basic insolvencies in a game of musical chairs. The assets upon which the instruments are based were never there or it is an attempt to increase the return on a paper asset after issued.

Dennis L.

I see it as a leverage issue – in the example given, leverage of 6X translates a 10% price drop into a 60% loss of funds. And what if the price drop is 20%, and the fund loses 120% of its value? Perfectly possible, given that the presence of forced sellers drives prices down further.

The same applies to housing. If someone buys a house for £300,000, and its value drops to £150,000, it will still keep the rain off. But what does the owner do about the £250,000 mortgage taken on to buy it?

I very much doubt, by the way, whether these funds took on leverage with loans from banks. Rather, this is the largely unregulated NBFI (“shadow banking”) sector in action. Banks, as deposit-taking institutions, are in the borrow-short/lend-long business, making multi-year loans with funds that customers can withdraw very quickly. They have experience in managing this activity, and don’t – well, we must hope they don’t – pursue small potential gains (as per the minor rates spreads involved in this leverage) by taking on ultra-elevated levels of risk. This reminds me of what happened to Northern Wreck.

The big question, I think, is: why isn’t this regulated?

excellent article, though it falters at the very end.

last paragraph:

“The point of the rather technical discussion of LDI, gilt yields and so on is simple: we will only get out of the UK’s prolonged economic rut if we diagnose the disease properly… Only then can we take actions that will truly get Britain back on track.”

obviously there can be no proper diagnosis without understanding energy economics.

The value of the article, for me, was the clarity with which it explained the LDI issue (which, by the way, is just one instance of dangerous leverage).

There’s no route “out of the UK’s prolonged economic rut”, but what is required now is better management, a more holistic approach (which contributes to social cohesion by addressing inequalities and inequities) and, of course, recognizing the economy as a surplus energy system.

An understanding of SEE couldn’t inject dynamic growth into the UK. But it could soften the hardships, and make Britain ‘more content with itself’.

I was a trustee of a DB scheme that went down the LDI route about 6 or 7 years ago. LDI is something that has been around for many years but was very complex to setup and only accessible for large schemes before large funds like BMO found ways to offer this to smaller schemes.

Our objectives were to try and match bond durations more closely to when liabilities were due, i.e. matching durations to the demographics of the fund. We hoped to reduce the proportion of the fund held in bonds and maybe increase higher return assets with some freed up cash. It was all very marginal. I don’t remember anything like 6x leverage being discussed or seeing such an example as that written in the article.

It was a 50/50 decision amongst our board with the chair carrying the vote. The impression I was given was that not going this route carried risks and that the regulator would see this in a favourable light as a means of stabilising the liabilities of an already massively underfunded scheme.

Soon after the employer along with the regulator (it was worried about bad publicly and I can’t say why because it might identify the fund) forced us to except an IVA and the fund went into the PPF (pension lifeboat). That’s another story though!

The Context for Future Economic Activity

The Gospel According to Albert Bates

https://peaksurfer.blogspot.com

Albert’s “biochar future” has been well described in his books. It essentially burns wood and puts a significant amount of carbon back into a non-volatile state, which also helps create more fertile soil capable of growing more plants.

IMHO, everything else is wishful thinking.

Albert has written a book on the multiple ways to make useful products out of wood while simultaneously producing the biochar. Whether one can support 9 billion people with such an economy is not a question I can answer.

I suggest that if one is thinking as much as a decade ahead, the issues that Albert raises need to be part of the context. Everything else is TV: “the context of no context”.

Don Stewart

@Don Stewart.

Can you give pointers to which articles on the Bates blog deal with “biochar”.

Just had a quick look and there are lots of articles to sift through.

Thanks

John

@John Adams

The best source is his book Burn: Using Fire to Harness Carbon to Help Solve the Climate Crisis. His co-author on that book was the woman who currently leads a Bio Char initiative. The book has a ton of uses for biochar, including things like putting it in toothpaste (if I remember correctly) and adding it to road surfaces. The BioChar can be produced with very primitive means (several Native American peoples made it long before Columbus). It does require something with carbon content that will burn…such as wood. The burning process can make lots of different products, from the char to electricity. The electricity isn’t enough to power a steel recycling machine, obviously.

I don’t have time right now to search for the most relevant article for you. Maybe in a couple of days.

Don Stewart

I agree with you that the dollar cost of an energy source is often more accurate than trying to draw consistent borders for comparative EROI calculations.

But that method comes with a giant flaw – external costs not charged to the source, as in CO2 emission costs (climate deterioration) not charged to fossil fuels.

Another externality example is that usually the costs of intermittency are not charged to renewables because grid stability is “paid for” by other generation’s capacity to stabilize the grid.

Yet people who grumble about the fact that renewables are intermittent don’t seem to be bothered by the fact that fossil fuel users aren’t required to capture and sequester the CO2 emitted.

I will also point out that even though you say “the single best indication of the total energy invested is the capital cost”, with which I agree, you dismiss renewables because they are built using some oil powered equipment, rather than based their levelized cost of electricity (the combination of capital cost and O&M).

A grid-tied energy system provides two “goods”, energy and capacity, both of which are essential because of the way we organize our economies, and energy systems also produce numerous “bads”, mostly in the form of environmental degradation. All of these benefits and costs should be included when comparing different energy systems.

@Joe Clarkson

I don’t think you are referring to my opinions. At any rate, I agree with what you say.

Don Stewart

@Don Stewart

Thanks for that Don.

I’ll see if I can get the book from my local library.

If not, I’ll have to suck on the corporate teat and buy a copy from Amazon.

I could always turn it into biochar once I’ve read it!!!!

Hi Tim – does the following announcement necessarily mean, from a SEEDs perspective (and noting that historic high correlation if not identity beween energy and economic activity), that the UK government is effectively seeking to reduce the size of the UK economy by (a corresponding) 15%?:

“…the UK sets a new ambition to reduce energy demand by 15% by 2030”

(https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-government-takes-major-steps-forward-to-secure-britains-energy-independence)

If ‘yes’, does this illustrate the disconnect between e.g. your modelling and the economics informing government policy?

Much of the energy consumed in a country like the UK is embedded in products imported from overseas, so the output/energy equation needs to be assessed globally. This said, in this specific instance it would not be surprising if the UK economy, as measured by SEEDS, did contract by 15% over that period.

On your broad question, no, they don’t get it. If you were to go back, say, ten years, you’d find similar growth projections and promises – but how have those panned out?

essentials are energy intensive, therefore discretionaries are relatively labor intensive.

Fig. 11 C:

the essentials segment grows but doesn’t necessarily gain jobs.

the discretionaries segment shrinks and definitely loses jobs.

the future is not bright.

Fig. 11 D:

PXE is about $100 trillion now and projects to about $55 trillion in 2040, so the decline is roughly 3% annually.

not bad for Haves, not good for Have-nots.

average per capita PXE now is above $10,000 annually, wow. Too bad it is skewed so heavily to the Haves.

by 2040 the average will be perhaps $5,000 which would still be great for those who are average or above.

since we are talking here about excess Prosperity after essentials have been covered.

otherwise, with a continuation of the highly unequal levels of Prosperity, on the PXE downslope there will be riotts and perhaps even revolution as citizens formerly with a personal plus PXE fall to zero.

Hi Tim,

I really appreciate the 3 tomes you have done to kick off 2023. The unfolding is becoming clearer every day and your language is very accessible for me to communicate with others.

Just a question on what you define as “essentials”. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics they exclude ‘Alcohol and tobacco’ classing them as non-discretionary items. However this is about 15% of CPI in terms of weighting if it was to be included.

I would assert that these items are in fact “non-discretionary/essentials” in that they are self-medication for various people (with a varying degree of efficacy and obviously have negative effects).

Regardless, it might be a moot point but if they were considered “essentials” in SEEDS does it matter?

Given that we can assume that these are addictive, in the event of cost increases, people may go out of their way to get these and/or they act as multipliers for social disruption/crime.

Food for thought for those agree with Dr. Morgans overall big picture, but disagree with some of the details.

https://thephilosophicalsalon.com/senile-economics-bubble-ontology-and-the-pull-of-gravity/

An interesting article. Part 4 in this series will set out the financial side of my interpretation.

Something else you may enjoy or not reading:

https://boriquagato.substack.com/p/nothing-is-obvious-to-scared-people

I understand why you don’t want to talk about this but its the elephant in the room sir and is connected to what you write about everyday. You can’t ignore it forever. An even larger financial crime then 2008 yet nobody talks about it. If those in authority commit crimes, how can you say “they don’t know” or “they don’t understand”?

Thought this might be interesting re shadow banking sectors

https://www.ft.com/content/87399d17-8d93-4a6a-a056-b062ed07ce79#comments-anchor

‘The move comes two years after an FCA-commissioned review found an “urgent need” to regulate the fast-growing sector.’

They really doesn’t want to do their job do they!

The FT is subscription only, but other sites have this story. What I’d like to know is where BNPL lenders get their capital, which I assume is either from NBFIs (shadow banks) or the wholesale market, or both.

I fear we are at the end of what technological improvements can do for Us. Example: car engines that shut off when waiting for a stoplight to change. The fuel savings are minuscule and take no account of the extra long term engine wear. And fiat currencies based on faith and credit which are just promises that someday will be meaningless.

Something weird happened. I posted a comment in answer to a John Adams question and a previous comment was substituted in its place. The comment was dated correctly, but the contents were from long ago. Any suggestions?

@Joe Clarkson

I was a bit confused with your response🤔🤣!

@John

All I said in my comment was that if you search “biochar” on Bates’ site, it comes up with a sequence of articles on biochar (many of them).

Thanks Joe.

I’ll dig a little deeper.👍

Albert Bates and Kathleen Draper on:

Burn: Using Fire to Cool the Earth

The first and easiest thing to do is to look up the book on Amazon. You will see a pretty good description. And you can click the button to listen to part of the introduction. The second thing you might want to do is listen to this interview:

If you are interested, you can buy the book from numerous places inexpensively. The book was written 4 years ago, so some of the technological thinking may not be exactly current. I will also note that, IMHO, the authors assumed that the world would not collapse before remedial action could be taken. But the last 4 years have indicated to many of us that nothing in the trajectory is going to change…perhaps unless we have a financial debacle which stops most everything or a nuclear war which destroys everything which we thought was worth saving.

Don Stewart

Thanks Don.

The book is on order! All sounds very exciting.

You are very welcome…Don Stewart

@Don Stewart.

Burn has arrived.

Very excited to start reading it.!!!

It is good. Odd that I haven’t heard about it before. What else do I not know!

@Barry

I’ve decided that, if the universe is infinite, them so too is the amount of things to know.

The percentage of everything there is to know that I know, is so infinitesimally small, that it’s virtually zero🤣🤣🤣

I have just put up the PDF version of The Surplus Energy Economy, part 1.

You can download it here.

This version has, on the last page, some supplementary data from the charts.

Please let me know if you find this helpful, or have any comments.

Maybe “First published 26th January 2003” will mislead some folk.

Well spotted!

I should have got out of my time-machine before posting!

Hello Tim,

The Bank of England is projecting growth at 0% out to 2026! Maybe they will agree with you soon.

Supply/Demand. The Bank bases supply on Capital & Labour. Is that correct? Does energy come into this at all? If so taxing the North Sea energy production to death would show up as a bad idea?

The 2073 Index-Linked Gilt had a real return of -2.3883% in 2021 that fits well with Seeds and LTG. You can now buy it with a small real positive yield that seems to good to be true with Seeds. Is this pricing in some sort of default? Or is it that the LDI funds at 5x leverage had distorted the earlier rate? An awful lot of gold plated Final Salary pensions depend on this promise being kept but is it another financial claim that will eventually evaporate almost like Bitcoin? Hyperinflation?

Hello Paul

I think I may have found the source of those projections – a monetary policy report published this month, showing growth not returning until Q1 2026, by which time CPI inflation is down to 0.4%, policy rate is 3.3% (i.e. above CPI inflation), and the unemployment rate is a lot higher than it is now.

SEEDS, as you may know, references underlying or ‘clean’ economic output (C-GDP), stripped of the cosmetic effect of credit expansion. This has the UK at 0% growth in 2023, falling to -0.3% by 2026 and -0.7% by 2030. As ECoEs rise, this translates into more severe declines in prosperity, whilst increases in the real costs of necessities exert tightening pressures on the affordability of discretionary purchases and capital investment.

I’ll look into the point about capital and labour.

“2026, by which time CPI inflation is down to 0.4%, policy rate is 3.3%”

Thanks Tim for pointing this out. Explains the Index-Linked Gilts.

Yes, I think so.

My broad perception, obviously informed by SEEDS but also by observation, is that the UK economy is in very bad condition. The report that we’re discussing may be using assumptions that look, to me, over-optimistic, where I’d cite affordability, property prices and discretionary sectors as having significant downside, and I would tag household credit (of all types) as an area of concern. In short, the Bank may come under increasing pressure, medium term, to lower rates, with CPI driven downwards by recession.

Here’s a quotation from the report which I think is instructive (my emphasis):

“And the Q4 growth rate is much stronger than expectations from earlier in 2022, when output had been projected to fall by almost 1%.

That difference largely reflects the Government’s Energy Price Guarantee (EPG) that was initially announced in September. The EPG has limited the squeeze on household real incomes owing to higher energy prices by capping the typical household dual-fuel bill”.

So Q4 22 GDP was expected to shrink by 1%, but this has been pared back to a much smaller decrease because the government has handed money to energy consumers. This money has been borrowed. QED – borrow more, GDP looks better.

This is exactly why SEEDS calculates underlying or ‘clean’ output (C-GDP) on an ex-credit basis.

Thank you for this fine and accurately worded analysis, with clear graphical representation, Dr. Morgan. It is clear why global financial capital desperately needs to crack Russia open for exploitation to keep the Ponzi scheme going a few more years. China has played-out in that capacity.

Of course, I feel that we should all take the bitter medicine of reality as soon as possible, but it appears that those at the controls would rather eliminate a lot of “useless eaters” in coming decades, to reduce the “capita”, while maintaining or increasing their own “wealth” and control.

Clearly, this is a dead end for even them, though a dead end for a lot of “capita”, which appears to be underway, already, with prospects for very rapid acceleration. (“We have the technology”, as they say.)

to me, it seems as though we are a civil society that has lost it’s way, our current collective motivation is to grow and increase prosperity, but this is being thwarted from all directions as we run up against limits,

that phase of the life of our civil society is over, yet we keep trying to return to it by using the nostrums that worked in the past,

we need a new vision, a collective motivation, a target to aim for, one that suits the reality of today not the reality of two centuries ago,

I think it’s pretty obvious that we’ve done all the growing that can be done and we’ve achieved material prosperity unheard of outside of the palaces of Kings in all previous eras,

the real challenge now is to sustain what we’ve achieved, not endlesly make futile efforts to achieve more,

sustainability has to be the new over arching goal, that which can’t be sustained is lost, if nothing can be sustained then everything is lost,

do we cling to notional valuations of assets and risk the whole house of cards tumbling, or do we accept a realistic valuation that can be sustained,

can we keep up the material living standards that allow us to live like Kings at the cost of the rest of the planet, or do we calm down and live well but not exorbitantly,

at the heart of todays challenge is coping with entrenched psychology, exacerbated by the century of the self and four decades of rampant consumerism and self interest.

ego, individualism, hubris and conspicuous consumption have turned our civil society into a collective delusional narcissist incapable of seeing the wood for the trees,

as our folly becomes apparent I find myself drawn to examining the Amish, their humility under the eyes of God and their respect for his Creation has motivated them to self impose limits, they’ve resisted material temptations of the 20th century that could disrupt the cohesion of their communities and maintained their largely 19th century agrarian lifestyle, one that they can sustain indefinately,

I can understand people baulking at the thought of religion, the Amish are the most austere branch of this Protestant tree, but they chose it for themselves and adapt it as they go along, it isn’t imposed from outside and it does seem to have put the brakes on their wilder impulses,

they do seem to have their inner demons under control, we in their outer world evidently don’t!

I found this fascinating and thought it worth sharing;

https://archive.org/details/theamishapeopleofpreservation/theamishapeopleofpreservation.mov

made respectfully in 1976, there were a few points that rather caught my attention.

John, Matt – thanks.

The plan has been to work step-by-step, and parts 1-3 might be called ‘gradual’ – relatively unspectacular rises in ECoEs, and declines in energy supply, economic output and prosperity. The only ‘rapid mover’ in these parts is the compression of affordability. This will change in part 4, where we turn our attention to finance. The economy might be able to contract gradually, but the financial system can’t.

So I am very grateful to you, and others, for engaging with this undramatic (1-3) project. I believe that we can move from what we know to what we want to know in measured steps using logic and modelling.

It’s wholly understandable that the richest aim to preserve or increase both their absolute and their relative wealth, but they might already realise that this isn’t possible. Wealth based on stock values can’t be monetized, so is purely notional or ‘paper’ wealth, and is destined to fall, particularly far in some sectors. Would ‘they’ be happy with (a) widespread poverty (and potentially anger) and a leveraged collapse in demand? The answer is likely to be ‘no’, once they recognize economic reality, and think through its implications.

Civil society has indeed lost its way. Ideally, the focus would be on prioritizing public services, ensuring that the essentials are available for all, and building a more harmonious society. At the moment, politicians and others promise “growth”. But this is something that they cannot deliver. Eventually, this failure to deliver will strip them of credibility, after which societies might move on.

“Civil society has indeed lost its way. Ideally, the focus would be on prioritizing public services, ensuring that the essentials are available for all, and building a more harmonious society.”

I don’t know about you but it seems to me they’re doing everything they can to not build a harmonious society. Quite the opposite actually, just look at how they stirred the pot with covid, trying to get neighbors to hate each other (not that it really takes that much)

Divide et impera

Those in control always think that they can maintain the status quo, but this isn’t possible under current conditions, because prosperity expansion has gone into reverse. Elites can’t defy economic gravity in perpetuity, but they can do a lot of harm whilst trying to do so.

Just a reminder that the coronavirus is excluded from discussion here, so we can concentrate on the economy.

Barclays analyst says

“UK investors have plenty of reasons to celebrate today as the FTSE 100 touched the magic 8000 level for the first time.”

The said investors in their balloon obviously are not “surveying” the real world.

Parachutes may be very hard to come by .

The FTSE 100 is dominated by multinationals for whom the UK is often a very small part of their operations.

Your broad point is right, though – asset prices have been ludicrously over-inflated in the “everything bubble”. I think we need to concentrate less on asset prices than on the sheer scale of liabilities, because this is where systemic risk is acute.

On the assets side, affordability compression – decreasing prosperity, more expensive essentials – is my preferred way of looking at this. Reduced affordability has implications for discretionary sectors, stream-of-income businesses and property prices.

When i did a brief stint as a lowly BNYMELLON employee, they had a sort of orientation for us newbies. I remember the the presenter asking some sort of question with regards to what was the largest pool of assets in the world to which i raised my hand and said Derivatives. He then told me that was “funny money” with which i agree and how BNYMELLON didn’t deal in those, but i’m rather sure that at the time (2013) and now they still show up as one of the larger holders of such. So their own spokesman wasn’t even aware of what kind of position they held in the “funny money”. Correct me if i’m wrong Dr. Morgan but don’t those positions dwarf the size of the world economy by quite a bit?

We have to tread a little cautiously with derivatives. We can come up with aggregate numbers which look scary – but, as with all liabilities, the questions are ‘owed by whom?’, and ‘owed to whom?’

With conventional debt, the answers are typically pretty straightforward. NBFIs – “shadow banking” – is more opaque, but we can still work out, generally, what I call ‘lines of oligation’. Derivatives, I suspect, are nearer to net-off. They may put individual institutions at risk, and this is not to be underestimated, but they are closer to being contained within the boundaries of the financial system. The problems in 2008-09 were lines of obligation linking non-financials (consumers, PNFCs) with financials.

The most recent info i could find:

https://www.usbanklocations.com/bank-rank/derivatives.html

And wouldn’t you know who tallies in at number 8 😉

The elimination of employees and services to reduce costs, to try to maintain or increase profits in the era of declining prosperity, has LETHAL consequences. Be forewarned, although there may be nothing you can do about it.

Re: the East Palestine OH train derailment:

“Wayside hot-box detectors — also called “hot boxes” — are typically placed every 25 miles along a railroad, according to a Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) report. Their use has contributed to a 59% decrease in train accidents caused by axle- and bearing-related factors since 1990, according to a 2017 Association of American Railroads study.