THE CONCLUSIONS OF THE SEEDS MAPPING PROJECT

Foreword

What follows is one of the longest articles ever to appear here, and certainly one of the most ambitious. The aim is to take readers all the way through the Surplus Energy Economics interpretation of the economy, from principles and background, via energy supply and cost, to environmental implications, economic output and prosperity, and the circumstances and prospects of individuals, the financial system, business and government.

Because what follows includes some commentary on business, readers are reminded that this site does not provide investment advice, and must not be used for this purpose. It is, as ever, to be hoped that issues of politics and government can be discussed in a non-partisan way, and that the principle of “play the ball, not the man” can be respected.

The reason for presenting this synopsis at this time is that the second phase of the SEEDS programme – the mapping of the economy from an energy-based perspective – is now all but complete. Three components of this programme remain at the development phase, but provide sufficient indicative information for use here. One of these is the calculation of “essential” calls on household resources; the second is conversion from average per capita to median prosperity; and the third is the SEEDS-specific concept of the excess claims embodied in the financial economy.

SEEDS began as an investigation into whether it was possible to model the economy on the right principles (those of energy) rather than the wrong ones (that the economy is simply a financial system). It was always going to be essential that results should for the most part be expressed in monetary language, even though the model itself operates on energy principles.

With prosperity calibrated, it then made sense to extend the model into comprehensive economic mapping. Aside from the three components still in need of further refinement, this mapping project is now complete.

For the most part, mapping as presented here is global in extent, though some national and regional data is used. If SEEDS is to continue, a logical next step would be to extend the mapping process to individual economies.

Lastly, by way of preface, this article is the most comprehensive guide to SEEDS and the Surplus Energy Economy yet published here, and it would be marvellous if readers were to see fit to pass it on to others as a way of ‘spreading the word’ about how the economy really works.

Introduction

Long before the coronavirus crisis, we had been living in a world suffering from a progressive loss of the ability to understand its own economic predicament. This lack of comprehension results directly from unthinking acceptance of the fundamentally mistaken orthodoxy that the economy is ‘simply a matter of money’.

If this were true – and given that money is a human artefact, wholly under our control – then there need be no obstacle to economic growth ‘in perpetuity’. This never-ending ‘future of more’ is nothing more than an unfounded assumption, yet it is treated as an article of faith by decision-makers in government, business and finance.

‘Growth in perpetuity’ is a concept which, though seldom challenged, is really an extrapolation from false principles. At the same time, those mechanisms which orthodox economics is pleased to call ‘laws’ are, in reality, nothing more than behavioural observations about the human artefact of money. They are not remotely equivalent to the real laws of science.

The fact of the matter, of course, is that the belief that economics is simply ‘the study of money’ is a fallacy, and defies both logic and observation. At its most fundamental, wholly financial interpretation of the economy is illogical, because it tries to explain a material economy in terms of the immaterial concept of money.

Logic informs us that all of the goods and services that constitute economic output are products of the use of energy. Other natural resources are important, to be sure, but the supply of foodstuffs, water, minerals and so on is wholly a function of the availability of energy. Energy is critical, too, as the link which connects economic activity with environmental and ecological degradation. Without access to energy, the environment would not be subject to human-initiated risk – and the economy itself would not exist.

Observation reveals an indisputable connection between the rapid material (and population) expansion of the Industrial Age and the use of ever-increasing amounts of fossil fuel energy since the first efficient heat-engines were developed in the late 1700s.

Two further observations are important here. The first is that, whenever energy is accessed for our use, some of that energy is always consumed in the access process. We cannot drill a well, build a refinery or a pipeline, construct wind turbines or solar panels, or create and maintain an electricity grid, without using energy. This ‘consumed in access’ component is known in Surplus Energy Economics as the Energy Cost of Energy, or ECoE.

The second critical observation is that money has no intrinsic worth, but commands value only as a ‘claim’ on the goods and services made available by the use of energy. Money can only fulfil its function as a ‘medium of exchange’ if there is something of economic utility for which an exchange can be made. Just as money is a ‘claim on energy’, so debt – as a claim on future money – is in reality a ‘claim on future energy’.

False premises, mistaken decisions

Critical trends in recent economic history can only be understood on the basis of energy, ECoE and exchange. ECoEs, which had fallen throughout much of the Industrial Age, turned upwards in the years after 1945 but, until the 1990s, remained low enough for their omission not to impose a visibly distorting effect on orthodox economic interpretation.

The point at which ECoEs became big enough to start invalidating conventional models was reached during the 1990s. The resulting phenomenon of economic deceleration was noted, and indeed labelled (“secular stagnation”), but it was not traced to its cause.

An orthodoxy resolutely bound to the fallacy of wholly financial interpretation naturally sought monetary explanations and monetary ‘fixes’. The idea that financial tools can overcome physical constraints can be likened to attempting to cure an ailing house-plant with a spanner. Its pursuit pushed us into ‘credit adventurism’ in the years preceding the 2008 global financial crisis, and then into the compounding and hazardous futility of ‘monetary adventurism’ during and after the GFC.

This has left us relying on false maps of a terrain that we do not understand. Almost all of our prior certainties have disappeared. We turned away from market principles by choosing financial legerdemain over market outcomes during 2008-09 and, at the same time, we abandoned the ‘capitalist’ system by destroying real returns on capital. The aim here is to present an alternative basis of interpretation that accords both with logic and with observation.

Beyond vacuous phrases which echo earlier certainties, governments no longer have ‘economic policies’ as such. Even the pretence of economic strategy was ditched when governments abdicated from the economic arena, and handed over the conduct of macroeconomics to central bankers. Asset markets have become wholly dysfunctional – they no longer price risk, and have been stripped of their price discovery function. The relationship between asset prices and all forms of income (wages, profits, dividends, interest and rents) has been distorted far beyond the bounds of sustainability.

Unless real incomes can rise – which is in the highest degree unlikely – asset prices must correct sharply back into an equilibrium with incomes that was jettisoned through the gimmickry of 2008-09. Efforts to prevent asset price slumps can only add to the strains already inflicted upon fiat currencies.

Ultimately, our manipulation of money has had the effect of tying the viability of monetary systems to our ability to go on ignoring and denying the realities of an economy being undermined by a deteriorating energy dynamic.

The energy driver

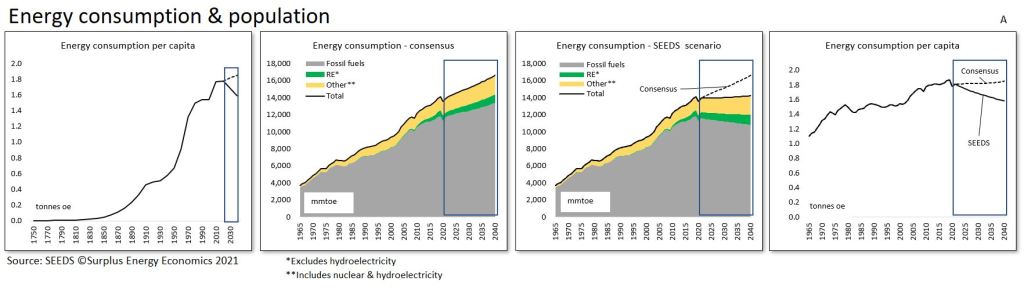

Our analysis necessarily starts with energy, a topic covered in more detail in the previous article. The informed consensus position, immediately prior to the coronavirus crisis, was that total energy supply would continue to expand, increasing by about 19% between 2018 and 2040.

Within this overall trajectory, renewable energy sources (REs) would grow their share of primary energy use, and the combined contributions of hydroelectric and nuclear power, too, would expand.

Even so, it was projected that quantities of fossil fuels consumed would rise, with about 10-12% more oil, 30-32% more natural gas, and roughly the same amount of coal being used in 2040 as in 2018.

These consensus views were (and in all probability still are) starkly at variance with a popular narrative which sees us replacing most, perhaps almost all, use of fossil fuels by 2050. The rates of RE capacity expansion that the popular narrative implies would require vast financial investment and, more to the point, would call for a correspondingly enormous amount of material inputs whose availability is, for the foreseeable future, dependent on the continuing use of fossil fuels.

SEEDS uses an alternative energy scenario which projects a decline in the supply of fossil fuels, a trajectory dictated by the rising ECoEs of oil, gas and coal. Essentially, the costs of supplying oil, gas and coal have already risen to levels above consumer affordability. The SEEDS scenario anticipates a pace of growth in RE supply which, whilst outpacing the 2019 consensus, necessarily falls short of a popular narrative which is as weak on practicalities as it is strong on good intentions.

The result of this forecasting is that the total supply of primary energy is unlikely to be any larger in 2040 than it was in 2018.

What this in turn means is that energy supply per person will decline. Such a downturn has only been experienced twice (to any meaningful extent) in the Industrial Age – once during the Great Depression of the 1930s, and again during the oil crises of the 1970s.

Neither of these downturns was physical in causation – they resulted from mismanagement, rather than changes in energy supply fundamentals – but both were associated with serious economic hardship and severe financial dislocation. Furthermore, what happened in the 1930s and the 1970s wasn’t really a downturn but, rather, no more than a pause in the upwards trajectory of energy use per person.

These parameters are illustrated in Fig. A. All of the charts used here can be enlarged for greater clarity, and all of them are sourced from the SEEDS mapping system.

Fig. A

It will be appreciated, then, that we have entered a phase – of declining energy availability per person – which can be expected to have a profoundly adverse effect on economic well-being and financial stability.

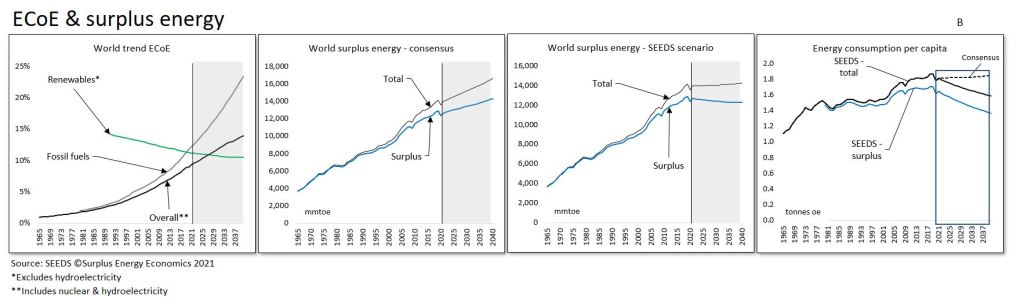

These effects will be compounded by a relentless rise in ECoEs that is most unlikely to be stemmed by the volumetric expansion of REs As we shall see, prosperity per person turned down at ECoEs of between 3.5% and 5.0% in the advanced economies of the West, and at rather higher (8-10%) thresholds in EM (emerging market) countries. But we cannot realistically expect that the ECoEs of wind and solar power will fall much below 10%. This means that they cannot replicate the economic value delivered by fossil fuels in their heyday.

Accordingly, surplus energy per person – that is, the aggregate amount of energy less the ECoE deduction – is set to decline, and would do so even if the over-optimistic consensus projection for aggregate energy supply could be realised.

Anticipated trends in ECoEs and the availability of surplus energy are summarised in Fig. B.

Fig. B

Cleaner, but poorer

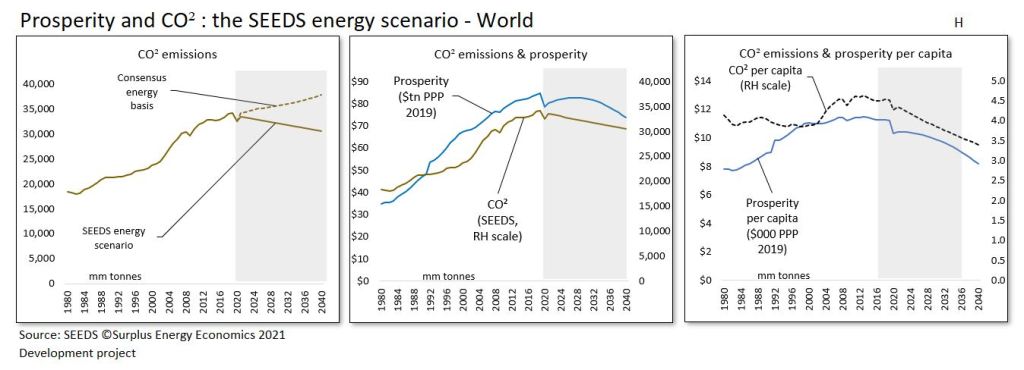

This does at least mean that annual emissions of climate-harming CO² can be expected to decrease. Unfortunately, this welcome trend will be a function, not of a seamless transition to an RE-based economy, but of deteriorating prosperity.

On the SEEDS energy scenario, annual emissions of CO² are likely to fall by 10% between 2019 and 2040, rather than rising by about 11% over that period. This, however, will correspond to a projected decline of 27% in global average prosperity per capita.

Some of the environmental projections that emerge from SEEDS mapping are set out in Fig. H. It need hardly be said that the relationship between the economy and the environment cannot meaningfully be interpreted until energy, rather than money, is placed at the centre of the equation.

Promises of a cleaner future are realisable, then, but assurances of a cleaner future combined with sustained (let alone growing) material prosperity are not.

Fig. H

Economic output

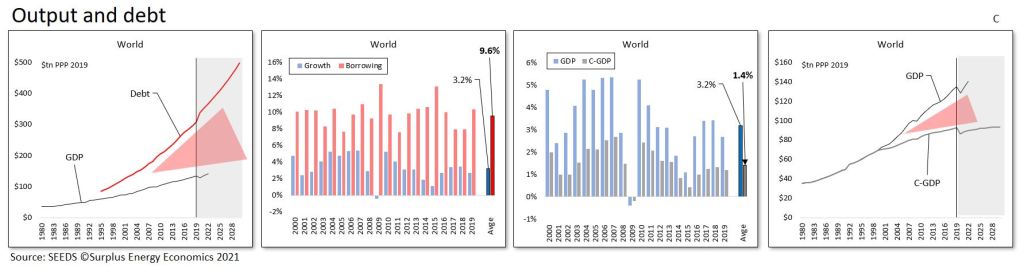

When we note that each dollar of reported economic expansion between 1999 and 2019 was accompanied by the creation of $3 of net new debt – and that GDP “growth” of 3.2% was supported by annual borrowing averaging 9.6% of GDP – we are in a position to appreciate that most (indeed, almost two-thirds) of all reported increases in GDP over the past two decades have been the cosmetic effect of credit and monetary expansion. If credit expansion were ever to cease, rates of growth in GDP would fall to barely 1.0% – and, if we ever tried to roll back prior credit expansion, GDP would fall very sharply.

Stripping out the credit effect enables us to identify a “clean” rate of growth in economic output that turns out to have averaged 1.4% (rather than the reported 3.2%) during the twenty years preceding 2019. As can be seen in Fig. C, the driving of a “wedge” between debt and GDP has inserted a corresponding wedge between GDP itself and its underlying or “clean” (C-GDP) equivalent.

Fig. C

Prosperity

With underlying economic output established, prosperity – both aggregate and per capita – can be identified through the application of trend ECoE. This reflects the fact that ECoE is the component of energy supply which, being consumed in the process of accessing energy, is not available for any other economic purpose. In terms of their relationships with energy, C-GDP corresponds to total energy supply, whilst prosperity corresponds to surplus (ex-ECoE) energy availability. SEEDS identifies the ratio at which energy use converts into economic value, and applies ECoE to establish the relationship between energy consumption and material prosperity.

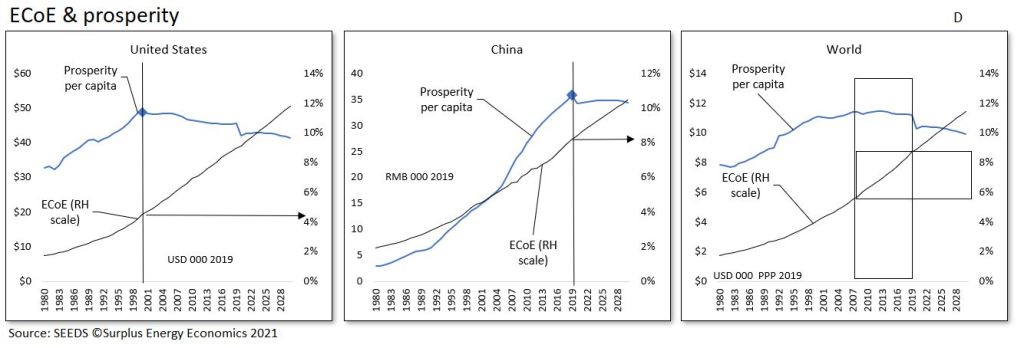

As well as providing our central economic benchmark, the calibration of prosperity enables us to establish the relationship between material well-being and trends in ECoE. In Western advanced economies, SEEDS analysis shows that prosperity per capita turned down at ECoEs of between 3.5% and 5.0%. In the less complex, less ECoE-sensitive EM countries, the corresponding threshold lies between ECoEs of 8% and 10%.

These relationships, identified by SEEDS, are wholly consistent with what we would expect from a situation in which energy costs are linked directly to the maintenance costs of complex systems.

Illustratively, prosperity per capita in the United States turned down back in 2000, at an ECoE of 4.5% (Fig. D). Chinese prosperity growth appears to have gone into reverse in 2019, at an ECoE of 8.2%, though, had it not been for the coronavirus crisis, the inflection point for China might not have occurred until the point – within the next two or so years – at which the country’s trend ECoE rises to between 8.7% (2021) and 9.1% (2023).

Globally, average prosperity per person has been flat-lining since the early 2000s, but has now turned down in a way that means that the “long plateau” in world material prosperity has ended.

This conclusion is wholly unidentifiable on the conventional, money-only basis of economic interpretation.

Fig. D

Financial

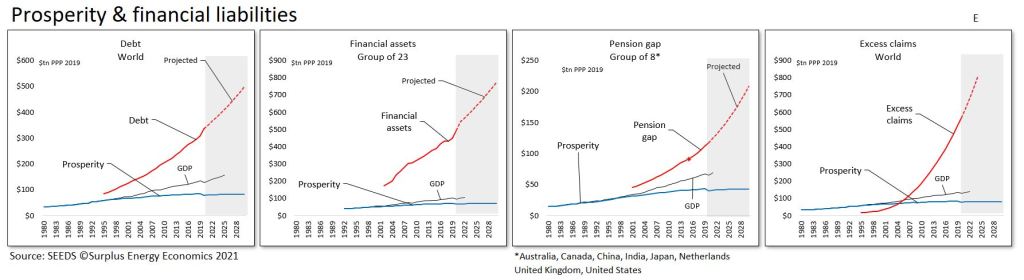

The identification of aggregate prosperity enables us to recalibrate measurement of financial exposure away from the customary (but wholly misleading) denominator of GDP. Four such calibrations are summarised in Fig. E.

Conventional measurement states that world debt rose from 160% to 230% of GDP between 1999 and 2019 – essentially, a real-terms debt increase of 177% was moderated by a near-doubling (+95%) of recorded GDP, leaving the ratio itself higher by only 42% (230/160).

This, though, is a misleading measurement, because it overlooks the fact that GDP was itself pushed up by the breakneck pace of borrowing.

Rebased to aggregate prosperity – which was only 28% higher in 2019 than it had been in 1999 – the ratio of debt-to-output climbed from 168% to 363% over that same period. Preliminary estimates for 2020 suggest that an increase of around 10% in world debt has combined with a 7.4% fall in prosperity to push the ratio up to 430%.

The second measure of financial exposure generated by SEEDS relates prosperity to the totality of financial assets. SEEDS uses data from 23 of the countries for which financial assets information is available, countries which together equate to just over 75% of the world economy,

On this basis, systemic exposure has exploded, from 326% of prosperity in 2002 (when the data series begin) to 620% at the end of 2019. Extraordinarily loose fiscal and monetary policy during 2020 suggests that this ratio may already exceed 730% of prosperity.

Gaps in pension provision are a further useful indicator of financial unsustainability. Back in 2016, the World Economic Forum calculated pension gaps for a group of eight countries – Australia, Canada, China, India, Japan, the Netherlands, Britain and America – at $67tn, and projected an increase to more $420tn by 2050.

Converting these numbers from 2015 to 2019 values, and then expressing their local equivalents in dollars on the PPP (purchasing power parity) rather than the market basis of exchange rates, puts the number for the end of 2020 at $112 trillion, which equates to 290% of the eight countries’ aggregate prosperity (and 180% of their combined GDPs). Pension gaps are growing at annual rates of close to 6%, a pace that not even credit-fuelled GDP – let alone underlying prosperity – can be expected to match.

The fourth measure of financial exposure produced by SEEDS is specific to the model. As we have seen, monetary systems embody ‘claims’ on a real (energy) economy that has grown far less rapidly than its financial counterpart. This has resulted in the accumulation of very large excess claims.

Calibration of this all-embracing measure, which is known in the model as E4, remains at the development stage. Indicatively, though, it informs us that the world has been piling on financial claims that cannot possibly be met ‘at value’ from the economic prosperity of the future.

From this it can be inferred that a process of systemic ‘claims destruction’ has become inevitable, suggesting that the process known conventionally as ‘value destruction’ cannot now be prevented from happening at a systemically hazardous scale. The most probable process by which this will happen is the degradation of the value of money, meaning that claims can only be met with monetary quantities whose purchasing power is drastically lower than it was at the time that the claims were created.

Measurement of excess claims forms part of a SEEDS national risk matrix which combines purely financial exposure with a number of other factors, one of which is ‘acquiescence risk’. This calculation references growing popular dissatisfaction induced by deteriorating overall and discretionary prosperity.

Fig. E

The individual

The ultimate purpose of economics is, or should be, the measurement, interpretation and (where possible) the betterment of the prosperity of the individual. Situations and projections can be expressed either as an average per capita number, or in amounts weighted to the median on the basis of the distribution of incomes. Average calibration is the primary focus of the model, but a new SEEDS capability (‘FW’) – being developed in response to reader interest in this subject – provides some insights into distributional effects.

As we have seen, the prosperity of the average person has been on a downwards trend in almost all of the Western advanced economies since well before the 2008 GFC. In ‘top-level’ prosperity terms, however, declines thus far have appeared pretty modest, even in the worst-affected countries – in 2019, British citizens were 10.4% poorer than they had been in 2004, with Italians poorer by 10.2% since 2001, and Australians worse off by 10.0% since 2003.

But top-line prosperity, like income, isn’t ‘free and clear’ for the individual to spend as he or she sees fit. Rather, prosperity is subject to prior calls, of which “essentials” are the most significant. Only after these essential outlays have been deducted do we arrive at the average person’s discretionary prosperity, meaning the resources that he or she can use to pay for things that they “want, but do not need”.

Measurement of discretionary prosperity produces rates of decline that are much more pronounced, and are distributed differently between countries, than the equivalent top-line calibrations. British citizens have again fared worst, seeing their discretionary prosperity fall by 32% between 2000 and 2019. The average Spaniard had 26.7% less discretionary prosperity in 2019 than he or she enjoyed back in 1999, whilst the decline in the Netherlands (also since 1999) was 26.5%. This decrease in the value of the discretionary “pound (or dollar, or euro, or yen) in your pocket” correlates directly to rising indebtedness and worsening insecurity, but does so in ways that are not recognised by policy-makers tied to conventional interpretation.

Of course, discretionary consumption has, at least until quite recently, continued to increase, even though discretionary prosperity has fallen. The difference between the two equates to rising per-person shares of government, business and household debt.

Calibration of discretionary prosperity obviously requires measurement of the cost of “essentials”. As mentioned earlier, this is one of the three components of the SEEDS mapping system that are still subject to further development. The conclusions which follow should, therefore, be regarded as indicative.

For our purposes, “essentials” are defined as those things that the individual has to pay for. This means that “essentials” include two components. One of these is household necessities, and the other is government expenditure on public services. These services qualify as “essentials” on the “has to pay for” definition, whatever the individual might happen to think about the services which he or she is obliged to fund. The government component of “essentials” relates only to public services, and does not include transfers (such as pension and welfare payments), which simply move money between people and so wash out to zero at the aggregate or the per capita level of calculation.

SEEDS analyses of prosperity per capita are summarised in Fig. F. In the AE-16 group of advanced economies, taxation (and transfers), being more cyclical, have tended to fluctuate more than spending on public services.

Together, the two components of “essentials” have moved up in real terms, even as prosperity has deteriorated, exerting a tightening squeeze on discretionary prosperity. Because of the credit effects which are interposed between GDP and prosperity, this squeeze cannot – despite its profound commercial, financial and political implications – be identified by conventional interpretation. It can be corroborated, though, by analysis of per capita indebtedness and of broader financial commitments.

As the charts show, relatively modest declines in the overall prosperity of citizens in America, Britain and Japan are leveraged into much sharper falls in their discretionary prosperity.

Fig. F

The median individual

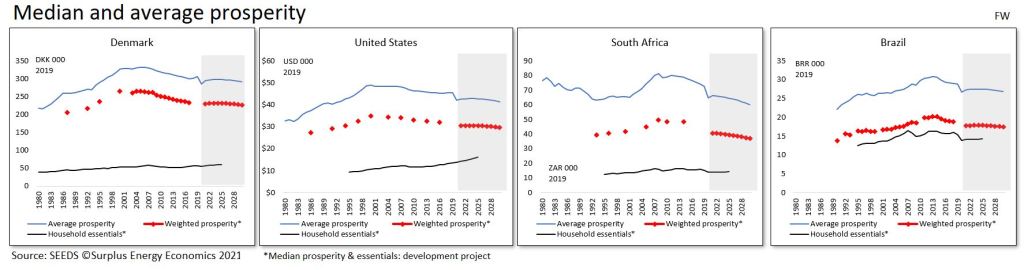

Of course, a country’s ‘average’ person is a somewhat theoretical figure, and one of the remaining SEEDS development projects addresses weighting for the difference between the average and the median person.

Because data for income distribution is intermittent, median prosperity per person is illustrated as dashed red lines in Fig. FW. These charts compare median with average prosperity per capita in four countries, and include the household (but, as yet, not the public services) component of “essentials”.

They show a comfortable margin in comparatively egalitarian Denmark (though the cost of public services in Denmark is relatively high). America remains a “rich” country – albeit less rich than she once was – in which household necessities remain affordable within the prosperity of the median person or household. But the situation in South Africa – and even more so in Brazil – must give rise to considerable concern.

Fig. FW

Business

Obviously enough, the compression being exerted on discretionary prosperity is of great importance to businesses, which are in danger of working to false premises when they rely on the promise of ‘perpetual growth’ provided by orthodox economic interpretation. Companies in discretionary sectors may not realise the extent to which their fortunes are tied to the continuity of credit and monetary expansion.

There are two critical (and related) points of context here. The first is that, as societies become less prosperous, they will also become less complex, rolling back much of the increase in complexity that has accompanied the dramatic economic growth of the Industrial Age. The second is that the proportion of prosperity subject to the prior calls of essentials will rise.

A logical outcome of de-complexification is simplification, both of product ranges and of supply processes. This will be accompanied by de-layering, whereby some functions are eliminated.

Two further factors which can be expected to change the business landscape are falling utilization rates and a loss of critical mass. The former occurs where a decline in volumes increases the per-customer (or unit) equivalent of fixed costs. Efforts to pass on these increased unit costs can be expected to accelerate the decline in customer purchases, creating a downwards spiral.

Critical mass is lost when important components or services cease to be available as suppliers are themselves impacted by simplification and utilization effects. It is important to note that falling utilization rates and a loss of critical mass can be expected to occur in conjunction with each other, combining to introduce a structural component into future declines in prosperity.

These considerations put various aspects of prevalent business models at risk, and this should be considered in the context both of worsening financial stress and of deteriorating consumer prosperity. One model worthy of note is that which prioritizes the signing up of customers over immediate sales. Previously confined largely to mortgages, rents and limited consumer credit, these calls on incomes now extend across a gamut of purchase and service commitments which can be expected to degrade as consumer prosperity erodes. This has implications both for business models based on streams of income and for situations in which forward income streams have been capitalized into traded assets.

Government

The SEEDS database reveals a striking consistency between levels of government revenue and recorded GDP. In the AE-16 group of advanced economies, government revenues seldom varied much from 36-37% of GDP over the period between 1995 and 2019. Accordingly, government revenues have expanded at real rates of about 3.2% annually. We can assume that similar assumptions inform revenue expectations for the future.

As we have seen, though, reported GDP has diverged ever further from prosperity, meaning that there has been a relentless increase in taxation when measured as a proportion of prosperity. In the AE-16 countries, this ratio has risen from 38% in 1995 to 49% in 2019, and is set to hit 55% of prosperity by 2025 based on current trends (see Fig. G4A).

It is reasonable to suppose that, as prosperity deterioration continues, as the leveraged fall in discretionary prosperity worsens, and as indebtedness starts to hit unsustainable levels, the attention of the public is going to focus ever more on economic (prosperity) issues. Politically, this means that what has long been a broad ‘centrist consensus’ over economic and political issues can be expected to fracture.

We can further surmise, either that the ‘Left’ in the political spectrum will revert towards its roots in redistribution and public ownership, and/or that insurgent (‘populist’) groups will campaign on issues largely downplayed by the established ‘Left’ since the ‘dual liberal’ strand emerged as the dominant force in Western government during the 1990s.

In practical terms, governments may need to adapt to a future in which deteriorating prosperity changes the political agenda whilst simultaneously reducing scope for public spending.

A ‘wild card’ in this situation is introduced by the likelihood that the deteriorating economics of energy supply may connect with the ECoE effect on the cost of essentials to create demands for intervention across a gamut of issues. These might include everything from subsidisation (and/or nationalisation) of essential services to control over costs, with energy supply and housing likely to be near the top of the list of demands for government action.

Fig. G4A

Pingback: When Does This Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham Finally Implode? - Bullion Forecast

Pingback: When Does This Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham Finally Implode? – Price of Silver

Spot on Tim. Energy is everything.

Did somebody here already post the link to this article on wind power economics (hint: there aren’t any) https://www.ref.org.uk/ref-blog/365-wind-power-economics-rhetoric-and-reality . The forecast 10-20 year outcome is eerily similar to the US “shale oil miracle”.

Came across another article recently on the theme of what “would happen if we had a source of unlimited and non-polluting energy?” The answer was that consumption would expand unchecked to the point where the surface temperature of the earth would stabilise at ~800deg C, approximating a black body.

We’re clearly on the downward, energy leg of this civilisation and need to scale back. But given human nature, nobody is ever going to win an election saying that, so the forecast is for things to just get more weird.

My green friends are all fervent believers in whopping solar arrays on their roofs, wind turbines everywhere and EVs to save us. Daring to challenge that is blasphemy and suggesting making doing with less is almost as bad.

Interestingly our grid provider has just disallowed new, domestic solar feed in locally, which is surprising considering we’re in a low density rural area. Presumably they’re worried about grid stability, so you now have to shell out for a battery if you want to get an ROI out of your solar.

Thanks Fred.

There’s a huge difference between the popular narrative of the future and the reality as we understand it here.

Taking – as just one example amongst very many – EVs.

The popular narrative is that ‘we’ll replace all of our current ICE cars and lorries with EVs’.

The reality is that:

– We don’t have the materials – such as lithium, nickel and copper – to make this possible

– If we did have these resources, mining them could have dire environmental consequences

– Mining and using these resources would require huge FF inputs

– We’re unlikely to have enough electricity to power a replacement EV fleet anyway

– Public transport would make far more sense for a lower-emissions economy

Plus:

– The powers that be probably don’t expect 1-for-1 replacement of the ICE fleet with EVs (but are not about to say so).