EXPLORING THE ‘PRECURSOR ZONE’

These are hard times for what British politicians ritually call “hard-working families”. Taxes have been raised to levels not seen since the post-War years. The ‘cap’ on the costs of electricity and gas has been increased by 23% so far this year.

Our focus here is on global economic issues, not local political ones, so this isn’t the place to debate whether the tax increases could have been implemented more equitably (which probably they could), or whether the additional revenues will be sufficient to fund the cost of social care for the elderly (which very probably they won’t).

The point is that paying more tax – and having to spend more on electricity and gas – leaves less money in the pockets of “hard-working families”.

Inflated asset prices may enable statisticians to claim that Britain has ‘never been wealthier’, and official figures continue to show “growth” in the economy.

But the inflated prices of property, equities and other assets are functions of the ultra-low cost of money, whilst “growth” in GDP is a conjuring-trick – comparing 2020 with 2000, aggregate British debt has increased by £2.8 trillion in real terms, whilst GDP has “grown” by just £400bn. Even this ratio – of £6.90 borrowed for each £1 of “growth” – understates the true extent to which “growth” has been bought with credit. Asset prices, meanwhile, cannot be monetized in aggregate, because the only people to whom an entire asset class can ever be sold are the same people to whom it already belongs.

GDP measures economic activity, whether as money spent and invested, or received as incomes. It doesn’t concern itself with where this money comes from, or connect recorded “activity” to a balance sheet showing forward commitments.

GDP thus measured can always be inflated by pouring credit into the economy. Within the parameters of currency credibility, GDP can be ‘pretty much whatever you want it to be’, so long as you can pour enough liquidity (which conventional economics calls demand) into the system.

In 2020, the year of the coronavirus crisis, British GDP fell by 9.9%, or £230bn, but that’s after the authorities had pushed more than £280bn of additional liquidity – borrowed by the government, and monetized by the Bank of England – into the system.

What we’re describing here is a flagging economy, with GDP juiced using credit expansion, at an adverse rate of exchange where nearly £7 of borrowing gets you £1 of “growth”. Meanwhile, the cost of essentials – whether purchased by households or provided by the state – is rising, whilst underlying prosperity is not. The overhang of liabilities – debt, other financial commitments and forward pension promises – keeps getting bigger.

We need to be clear that these problems are by no means unique to the United Kingdom, and are worse in other countries, including the United States. The situation may look better in some of the EM (emerging market) economies, but all this really means is that the West has already encountered problems which, for some Asian countries, still lie in the future.

What we’re experiencing, at least in economic terms, is the approach of The Limits to Growth (LtG), as forecast back in 1972 by Donella Meadows, Dennis Meadows, Jørgen Randers and William Behrens. Recent analysis by Gaya Herrington has used intervening data to demonstrate, first, that the authors of LtG got it right, and, second, that we may be within “a decade or so” of the point at which growth comes to an end.

If this is indeed the case, it’s highly unlikely that the ending – and, in all probability, the reversal – of growth will be an event, narrowly identifiable in time. It’s always been likelier that this would be a process, characterised by (a) economic deceleration, and (b) increasing stress on all systems that are – like the global financial system – wholly predicated on growth.

This is exactly where we are now. To be more specific, the world economy entered what we can call a precursor zone back in the 1990s. That was when observers began to worry about “secular stagnation”, and the authorities embarked on ‘credit adventurism’ – and, latterly, on ‘monetary adventurism’ as well – in an effort to ‘fix’ a problem that they didn’t understand.

Once we’re clear about the real dynamics of the economy, we can see why growth has been tipping over into involuntary “de-growth”, and we can also understand the lead-indicator mechanics of the “precursor zone”. Growth has flagged for reasons which have little or nothing to do with money, and everything to do with the energy dynamic which really determines prosperity.

Unable to understand this process, and shackled to the imperative of delivering ‘growth in perpetuity’, decision-makers have poured ever more credit into the system, much of it monetized by central banks. Though efforts have been made to improve regulation of the banking system since the 2008-09 global financial crisis (GFC), much of the subsequent expansion in credit has occurred in the unregulated ‘shadow banking’ system.

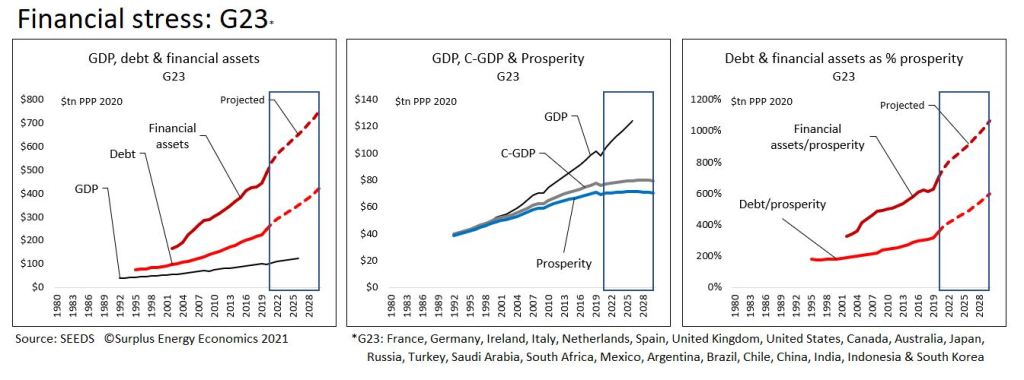

For a group of twenty-three economies (G23) for which fully comprehensive data is available – and which, between them, account for 80% of the global economy – aggregate financial assets (which, for the most part, are the liabilities of the non-financial economy) now stand at an estimated 495% of GDP, up from 300% back in 2002.

Even this ratio increase is a severe understatement of the real extent of exposure, because credit and monetary expansion has inflated GDP to levels far ahead of underlying economic prosperity. If we measure the financial assets of the G23 countries against prosperity, the ratio already stands at about 700%.

Regular readers will be familiar with the concept of prosperity, and how it differs from the increasingly misleading conventional measure that is GDP. The first point to be understood is that economic output is a function of the use of energy, because nothing that has any economic utility at all can be supplied without the use of energy. The history of the Industrial Age has been one of using ever larger amounts of energy to deliver economic value at rates of growth which, until quite recently, exceeded the rates at which population numbers were increasing.

The second critical point is that, whenever energy is accessed for our use, some of that energy is always consumed in the access process. This ‘consumed in access’ component is known here as ECoE (the Energy Cost of Energy). The role played by ECoE is that it’s the difference between economic output (a function of the use of energy) and prosperity (which is what remains after the deduction of ECoE).

This understanding provides us with an equation which, in principle at least, is comparatively straightforward. Prosperity is a function of the quantity of energy used, the value and cost of that energy, and the number of people between whom the resulting aggregate is shared. Money isn’t an intrinsic part of the prosperity equation, but acts as a proxy and a medium of exchange – money has no intrinsic worth, but commands value only as a ‘claim’ on the products of the energy economy.

In recent times, the prosperity calculus has become a constrained equation, in which the constraints are (a) the rising ECoEs of energy supply, and (b) the limits to environmental tolerance of the use of fossil fuels.

The only way of breaking out of these constraints would be to find an alternative source of energy which delivers low and falling (rather than high and rising) ECoEs, and can be utilized without causing environmental harm. Desirable though their expansion undoubtedly is, renewable sources of energy (REs) such as wind and solar power cannot meet these requirements. Their expansion, maintenance and replacement are dependent on legacy energy from fossil fuels, and their ECoEs are highly unlikely ever to be low enough to support current levels of prosperity, let alone allow for a resumption of “growth”.

As the following charts show, even the rapid expansion of RE capacity cannot be expected to do more than blunt the rate at which overall ECoEs rise. The pace at which global aggregate prosperity has been growing has decelerated markedly since we entered the precursor zone in the 1990s, and we are now at or very near the point where aggregate prosperity starts to shrink. Because aggregate prosperity growth has fallen below the rates at which population numbers have continued to increase, prosperity per capita has already turned down.

As this ‘top-line’ measure of prosperity per person has turned downwards, the cost of essentials has continued to rise, in part because many necessities are at the high end of the energy intensity spectrum. This means that the discretionary (ex-essentials) prosperity of the average person in each of the Western economies is already under increasing pressure, as typified in the charts for Japan, the United States and the United Kingdom.

‘Essentials’ are defined here as the estimated total of household necessities and public services provided by the government. The British situation exemplifies the rising trend in essentials – taxes have had to be increased to fund public services (in the current instance, health and social care), whilst rises in the costs of electricity and gas reflect trends which can be expected to extend to other energy-intensive necessities, not just in Britain but across the world.

As well as a deterioration in prosperity which is adversely leveraged at the discretionary level, this situation also leaves us trying to support an ever-growing burden of financial commitments on a static and, in due course, contracting basis of aggregate prosperity.

The final set of charts illustrates this process with reference to the G23 countries which represent four-fifths of the global economy.

Since we entered the precursor zone in the 1990s, both debt and broader financial assets have grown much more rapidly than GDP. Output reported as GDP has itself been inflated by credit expansion, and now far exceeds both underlying output (C-GDP) and prosperity.

Measured against prosperity, both debt and broader liabilities have become unsustainably large, pointing towards either the ‘hard’ default of repudiation or the ‘soft’ default of inflationary devaluation.

Asset prices, meanwhile, have been driven to highly over-inflated levels, primarily because the prices of assets move inversely with the cost of money. We might suppose that asset prices will remain at inflated levels until the liability side of the equation reaches the nemesis of hard or soft default.

Examination of the precursor zone and the dynamics of falling discretionary prosperity do, though, suggest that another process might trigger asset price slumps. Equity markets are dominated by the suppliers of discretionary goods and services, which is likely to worry investors once they realise that the scope for discretionary consumption, already propped up by the continuity of credit expansion, is shrinking. At the same time, the affordability of property is linked to incomes on a post-essentials, credit-adjusted basis.

“We’re betting everything on ‘EVs, powered by REs’. What if that doesn’t work? Or what if EVs are affordable only for a minority?”

Maybe as the saying goes “that’s not a bug, that’s the feature”!

I’d agree. This is basically the prologue to degrowth unfolding, because the price rises in many instances along with shortages, will cut out a lot of people who will have to make do without.

It’s like going back to a time when only the rich flew abroad and owned cars. Cheap, abundant FFs basically enabled the masses to partake, and now that the music has stopped, it’s time to see who gets a chair.

That or humans take on a moral imperative so that the ideal is everybody sharing everything, with certain caveats of course.

Since most of the systems interact with one another in a nonlinear way, I doubt there is a contingency plan B as such, just a need for adaptive systems that can work efficiently with new information.

Heterodox economics is still an emerging field and one which I haven’t had the time to explore but I’d imagine the starting point would be calculating the energy capacity of the system and working backwards from there along with an assessment of what is essential and discretionary and using state transfers and intervention to build fairness in the system.

As such, much of my political work these days is trying to reinforce a sharing cooperative mentality which is not easy whilst we have the freedoms afforded by material prosperity to have widely divergent views. Therefore, part of my work is to reinforce the notion of superordinate goals and notions of unity.

Last time I checked, the world had 1.1 billion cars (and 800 million commercial vehicles).

The case for conversion to EVs imposes a second layer of resource requirements.

First, we need material resources to increase wind and solar capacity, create a huge infrastructure, and provide back up (presumably batteries) for intermittency.

Second, EVs add a whole extra set of resource requirements, often of the same materials (such as batteries). Electric motors are simpler and lighter than ICE engines, but batteries can never match the energy density, low cost and simplicity of a fuel tank.

The latter might be ‘an ask too far’, which is why a ‘plan B’ – trams, trains – might be a good idea.

Certainly in Birmingham, UK, the tram network is expanding with another recent bid looking to expand it further.

https://www.birminghammail.co.uk/news/midlands-news/four-new-tram-routes-birmingham-21592574.amp

Thanks for the regression to the mean, very interesting.

@Matt

Re the power elite bailing out due to a self-destruct drive: do you think they are less well adapted than Mary and Joe Sixpack?

Your example is an exception that proves the rule. (Afghan President) Think about Putin and his third decade, the Royals and landed nobility in the UK and elsewhere with centuries of wealth and power. There have been many depressions, and most of their power endured.

If civilization collapses, remote hunter-gatherers and subsistence farmers and fishermen likely do the best based upon their current skills.

Historically, elites haven’t abdicated. The question is whether they can or can’t adapt.

The French and Russian revolutions, like many others, had common features. The leaderships were isolated, and out of touch with what was happening. The economy was in trouble, and the public (aka ‘peasantry’, ‘proletariat’) were suffering economic hardship and severe inequality. The elites relied on their command of power (force), information (intelligence, informers) and money.

An obvious statement is that reform is the best way to prevent revolution. Don’t concentrate wealth too much. Don’t make inequality (in its many forms) too blatant. Stay informed, not relying on what sycophants choose to tell you. Make concessions when tactically advantageous. Ensure the public doesn’t experience extreme hardship. Don’t rely too much on the combination of intelligence, force and money.

You could, and perhaps still can, study this stuff at university. I took it as an optional paper at Cambridge.

the British Royal family and landed nobility did get pushed out of their American colonies by the American War of Independence,

an Empire, that the sun never set upon at that time, is today reduced to the Home Island and even the northern territory, Scotland, is seeking to break away,

stupidity knows no borders or class barriers, it is a universal human reality,

various Prince Williams succeeded in gaining the popular epithet of “Silly Billy” for their impressive accomplishments in the field of applied semi-idiotics.

wealth and privilige do not neccessarily confer wisdom automatically.

I’ve always thought that the British Empire collapsed almost overnight. As of 1956, and although India gained independence in 1947, the rest of the Empire was intact. By 1960, most of it was gone. This was a panic, after Suez demonstrated that Britain was no longer a major player. This period – 1956 to 1963 – was a time of rapid cultural change, the era of ‘Look Back in Anger’, Profumo, spy scandals and, at the end, the Great Train Robbery, which poked fun at ‘the establishment’.

Matt,

Again you cherry pick examples. The US has grown its own ‘nobility’ (billionaires). This began with industrialists in things like shipping, railroads, oil, agribusiness.

I never said all the powerful were tops in brains. But most of them successfully find and hire brains as well as muscle. And revolts have occurred, but they are the occasional exceptions. If you haven’t noticed, within a couple of generations, new power-elites gradually step into the boots of the vanquished.

revolutions in thinking and actual physical revolutions, as in the deposing and ousting of ruling elites, seem to come in waves,

the French Revolution and the American War of Independence occurred in the same historical time frame,

the Russian revolution of 1917 struck fear in ruling elites across the world for fear that ‘the contagion might spread’

for the US today it is conceivable that the collapse of the regime in Afghanistan could be followed by American withdrawal from Iraq, Syria and reversals of influence in Saudi Arabia and the Lebanon,

once change happens it can build momentum and become impossible to stop,

it’s possible that the Afghan debacle might become America’s Suez moment.

Matt,

I’ve over 1/3 my cash equivalents out of the $US, plus physical gold. I’ve seen a decline as likely and written about that here. I even compared it to the UK last Century when the Pound went from $5 to $1.

This discussion was about the power elite (as a general class globally) going tits up from incompetence. Some assuredly will if/when some civilized societies implode. As I wrote last eve, the least developed have the skills to survive if that happens. The proletariat is likely chopped liver.

Revolutions Are Complicated and also Complex

*Most of the time, talk of collapses or revolutions revolves around the political. When the American States won their War of Independence against the British Crown, did that change the elites? Well, no, not really. The Crown had tried to impose some pretty modest taxes on tea and so forth. But for many people in America, the day to day power was the slave owner. Slaves were the primary ‘property’. And the founding documents of the US wavered between ‘protection of property’ and ‘pursuit of happiness’. The radicals like Tom Paine were eventually removed from positions of influence, and Thomas Jefferson kept his slaves. If we take the long view, it was really the arrival of fossil fuels that either eliminated slavery (including it’s derivatives after the Civil War), or, if you prefer, changed the form of slavery quite radically.

*Today we all know what the words ‘wage slavery’ imply. So has there been a revolution?

*Humans are, as a gift of evolution, heterotrophs:

“A heterotroph is an organism that cannot produce its own food, instead taking nutrition from other sources of organic carbon, mainly plant or animal matter. In the food chain, heterotrophs are primary, secondary and tertiary consumers, but not producers. ” And so, at a very basic level, we are dependent on what we consider to be ‘lower’ forms of life. Fossil fuels give us the illusion that we are ‘free’, but in reality we are part of the web of life as it has evolved on Earth over the last few billion years. We are radically interdependent, while many of our memes revolve around ‘independence’ for the average person and ‘dominance’ for the political class and business elites. The clash between what is and what we want and believe is now playing out. The Limits to Growth study and Greer’s current very good article on the subject are a far better explication of our predicament than most competing frameworks of analysis.

*Evolution on Earth, ignoring catastrophic physical disturbances such as meteors and massive volcanic events, is best thought of as a long evolution toward recycling carbon, the primary unit of energy. Fossil fuels are an aberration which has allowed us to create a world which is very likely finite and near its limits.

*One popular way to escape the radical interdependence and the fragility and decay aspects is to convince ourselves that heaven awaits us…or at least awaits a chosen few. This view point made slaves more quiescent than we might expect them to have been just from looking at their material condition. Some elites believe in heaven, but I think a majority are now thoroughly cynical and believe that this is all there is and get as much of it as one can. Gather those tokens that Greer insists are ultimately without value.

It is enlightening to think about horticultural and hunting/ gathering societies as escapes from humans dominating humans, but they do not change the basic fact that we are heterotrophs.

Don Stewart

Pingback: #211. The case for contingency planning | Surplus Energy Economics

@ those seeing RE as a solution:

Capacity Factor: Why solar and wind are impossible fantasy.

https://brianhanley.medium.com/capacity-factor-why-solar-and-wind-are-impossible-fantasy-a2d15059011

This is why I judge nuclear to be rapidly advancing by mid century. (Thorium preferred)

Wind and solar energy probably have an ECoE of 100+ when you take into account that they are not stand alone entities but always need fossil backup. But this fact is hardly ever mentioned. Therefore, the CEO of Seaborg Technologies, Troels Schønfeldt, has given up on the Danish mind set and policy towards small, inherently safe and very low cost nuclear plants and has got investors from South Korea and one big Danish investor in order to realize his ideas. It is strange that a country which has decided to rely almost entirely on wind and to a smaller degree on solar energy has come up with a start up firm which already now has cracked problems with regard to solutions of the negative aspects of nuclear energy.

https://www.seaborg.co/the-reactor