CRASH RISK, NEOLIBERALISM AND “SECULAR STAGNATION”

With their resigned but widening acceptance of “secular stagnation”, the powers-that-be are inching ever closer to a recognition that growth, at least as we have known it, isn’t going to return to previously-experienced levels. It seems a short step from “low growth” to “no growth at all” (which would not, of course, come as any great to surprise to the author of Life After Growth).

Indeed, when we factor-in the depressing effect of population expansion on per-capita GDP, even “secular stagnation” takes us into a new era.

Let’s reflect on what this means. Individuals can no longer assume that they are going to get better off over time, or that each generation will be more prosperous than its forebears. People and businesses can no longer take decisions on the assumption that wealth, or real asset values, or the size of the market, are going to keep getting bigger. Governments cannot plan on the basis of an expanding economy, or tax revenues that increase from year to year.

These are profound changes, not just in financial terms, but also in how we think about government and the economy.

That, and the importance of the subject, is why this discussion is longer than usual.

My aims here are as follows. The first is to look at the implications of a “low growth” (or even a “no growth”) economy. The second is to relate a slowing economy to a debt mountain that keeps getting bigger, and to ask what we are going to do about our debt burden now that we can no longer expect to “grow out of it”.

The latter question is the easier of the two to answer. I am more convinced than ever that a financial crash is inevitable. Moreover, I think we can begin to see, not only where it is likeliest to happen, but the form that it’s likeliest to take. As outlined later, we can now identify four directions from which the next crash is most likely to come.

As for the near-disappearance of growth, resulting changes are likely to include the ditching of the doctrine of economic “neoliberalism” and, as the price of failure, a further weakening of incumbent elites which already facing a popular backlash.

Low growth – the three causal factors

To start with, though, we need to examine why it is that growth has become so feeble. Once we are clear about the causes of weak growth, we can understand the role of theory and policy, and then move on to look at consequences.

Opinion is divided about why growth is so low. Some, even amongst the opinion-formers and decision-makers, are starting to question the efficacy of “neoliberal” economics. Sometimes known as “the Washington consensus” or “the Anglo-American model”, this doctrine has ruled the roost since it supplanted Keynesian economics in the 1970s. Of course, doubters in the upper echelons are few in number – so far, anyway – and most of them assert that neoliberal economics is solid and robust.

Well, to paraphrase Mandy Rice-Davies, “they would say that, wouldn’t they?”

The first cause of low growth is an escalating uptrend in the cost of energy. The key parameter here is the “energy cost of energy” (ECoE). As readers will know, energy is never “free”, but has a cost in terms of the amount of energy that is consumed for each unit of energy accessed.

Though market prices oscillate widely – largely in response to cyclical patterns – underlying trend ECoEs have been rising relentlessly for several decades, and have been acting as an increasingly heavy drag on growth since about 2000. In that year, according to SEEDS (the Surplus Energy Economics Data System), trend ECoE reduced GDP by about 4.2%, up from 2.8% a decade earlier but still small enough not to be noticed within normal margins of error when calculating economic output.

Today, however, SEEDS puts trend ECoE at over 8% of GDP, which is more than enough to explain the virtual disappearance of growth.

Still, nothing is ever so bad that policy mistakes cannot make it worse. The second and most obvious brake on growth has been escalating debt, which can, in large part, be traced to the mishandling of globalisation.

Because Western businesses chose to export skilled, highly-paid jobs without accepting a corresponding reduction in consumption, debt was driven upwards by the need to bridge the gap between weakening real incomes and rising consumer spending. The banking system made this resort to borrowing possible, aided and abetted by government and central bank preferences for impaired surveillance (under buzz-phrases such as “light-touch regulation”) and unduly loose monetary policies.

In addition to rising resource costs (measured as energy inputs), and the choice of policies geared to increasing debt, a third factor contributing to weak economic performance has been a loss of interest in growth. That governments and societies have chosen growth-reducing policies may seem such an outlandish idea that a brief explanation is required. Once explained, it becomes apparent that policy has sabotaged growth, to a very striking extent.

Essentially, there are two broad ways in the individual can pursue wealth. One is to invest effort and capital developing a business, pioneering new products and services. This is hard work, and is subject to considerable risk and uncertainty, but it is a major driver of economic expansion. It can be called the “entrepreneurial” route to betterment.

The alternative is the “speculative” route, which involves investing money in assets and profiting from a rise in their value. Whilst it can make individuals wealthier, speculation does not contribute to growth in the economy.

Obviously, therefore, the role of policy should be to ensure that the entrepreneurial route, rather than the speculative one, is followed as extensively as possible. This means ensuring that incentives favour innovation rather than speculation.

In short, policy can sabotage growth if it incentivises the speculative and deters the entrepreneurial, and this is exactly what all too many Western governments have done. Both regulation and taxation have made the entrepreneurial route unattractive, whilst fiscal and monetary policy has favoured the speculative. Governments have not only operated loose monetary policy, but have, through deregulation, made it easier to borrow. Additionally, capital gains tend to be taxed at lower rates than income, whilst states have demonstrated their preparedness to backstop property markets, reducing speculative risk to levels far below entrepreneurial risk.

In this way, Western governments have steered their populations towards speculation and away from entrepreneurship. No government which does this has much right to complain – though they still do – when innovation and productivity deteriorate, because incentives and risks have been skewed in favour of speculation and against entrepreneurship. To this extent at least, Westerners, at the instigation of their governments, have actively chosen a path of low growth.

Culpability? “Secular stagnation” and neoliberal economics

Given these three causal factors in the deterioration in growth, to what extent are neoliberal doctrines to blame?

It needs to be understood that, though avowedly a philosophy of market economics, neoliberalism actually differs a great deal from anything that Adam Smith would have put his name to.

For a start, neoliberalism puts much less emphasis on free and fair competition, and lacks Smith’s absolute loathing of monopoly and excessive concentration (which, famously, he called “a conspiracy to defraud the public”). It lacks, too, the logic implicit in Smith, which is that the state has a crucial role to play in saving capitalism from its own excesses. Neoliberalism is far more supportive of corporatism than Smith could ever have been, and, where Smith emphasised the benefits of competition to society as a whole, neoliberalism is a worshipper at the altar of unrestricted private profit.

Therefore, it is perfectly consistent for followers of Smith to castigate neoliberalism as a self-serving variant.

This is just as well, because it is pretty clear that neoliberalism has played an active part in driving growth downwards. This is not the only reason why the neoliberal consensus is heading for the shredder, but it suggests that populist opposition to neoliberal doctrines has a solid basis in logic.

Though neoliberalism cannot be blamed directly for the escalating trend cost of energy, even here there is some culpability. Countries most addicted to neoliberalism – amongst them, Britain and America – have all but abandoned the direction of their energy futures.

Shales have not conferred energy self-sufficiency on the United States and, even before the recent falls in prices and the near-collapse of investment, shale output was always expected by the authorities to reach peak output shortly after 2020. In Britain, where energy production has already halved over ten years, successive governments have dithered over nuclear power, finally selecting the costliest, least reliable technology on the table, and relying on overseas investors to fund its development. Softening regulation, and announcing “life extensions” for the existing nuclear fleet, may be safe enough – though I’m glad I don’t live anywhere a “life-extended” plant – but do not address the fundamental issue.

Where soaring debt is concerned, neoliberal doctrines are “guilty as charged”. Western governments have supported a form of globalisation geared almost entirely to the furtherance of corporate profitability, and have been complicit in the expansion of debt necessary to bridge the widening chasm between domestic production and consumption.

It is over the third growth-destroying trend – the loss of interest in growth – that neoliberalism is most culpable. Governments, citing neoliberal logic, have pursued policies which skew incentives in favour of speculation and against entrepreneurship.

On the entrepreneurial side, states have pursued ever-increasing regulation, sometimes for good reasons of safety and quality, but in other instances in pursuit of social policies dear to the hearts of the self-styled “liberal elites”. Taxation often bears much too heavily on small and medium enterprises (SMEs). This is typified by the British system of Business Rates, a tax which, being wholly unrelated to turnover, let alone profitability, is the small-business equivalent of a dose of strychnine.

In contrast to this, governments have favoured and incentivised speculation. They have made borrowing both cheap and easy-to-access, and have exacerbated this trend since the banking crisis, the logic seemingly being that economies can “borrow their way out of a debt problem”. In many countries, capital gains are taxed at rates lower than median incomes, and gains made on property are often exempt from taxation altogether.

Policies designed to boost asset prices – most notably the infusion of newly-created money through quantitative easing (QE) – should, at the very least, have been accompanied by the taxation of policy-created gains. Almost unforgivably, they were not. Governments have made no secret of their willingness to backstop property prices, thereby lending powerful support to the speculative route to wealth.

Nemesis #1 – the coming crash

So much for the causes of low (or no) growth, and the complicity of neoliberalism. What happens next?

Though few in authority seem to have made the connection – or, more likely, have decided not to talk about it “in front of the children” – “secular stagnation” further increases the already-strong probability of a coming crash. Put simply, the burden imposed by debt becomes much heavier if growth is much lower than had previously been assumed.

Such a crash is, of course, implicit anyway in the transformation of the global economy into a giant Ponzi scheme, where each dollar of reported “growth” comes at a cost of almost $3 in net new borrowing, and where most of the “growth” itself is phoney, since it amounts to nothing more than the spending of borrowed money.

Those entrusted with global economic and monetary policy seem wholly incapable of learning from past experience. The 2008 banking crisis came about because “real economy” debt (which excludes the purely inter-bank sector) increased by $38 trillion over a seven-year period in which nominal GDP rose by $17 trillion.

In the seven years after the crisis, when nominal GDP again increased by $17 trillion, borrowing rose to $49 trillion, from $38 trillion in the earlier period. In response to the crash, governments slashed both policy and market interest rates to prevent the burden of debt service from overwhelming the system. In so doing, they made borrowing far cheaper than at any point in financial history, which necessarily created huge asset bubbles whilst accelerating the rate at which we are mortgaging the future.

This has to end with an implosion, since this outcome is hard-wired into all Ponzi schemes.

Of course, “secular stagnation” ups the ante where a crash is concerned. Since the only circumstance in which a debt burden can become less onerous is where the income of the borrower increases, a deterioration in growth (to levels below prior planning assumptions) has the effect of making debt harder to service, and bringing the looming crash even nearer.

We can now identify four areas where the next crisis is likeliest to start. And, of course, if any one of these risks eventuates, it further increases the likelihood of sympathetic detonations elsewhere.

Risk 1 – China

The first area of exposure is China, where it is necessary to look behind the obvious. The “obvious”, of course, means faltering growth and escalating debt. Though the government claims that GDP is still growing at around 7%, it is very hard to reconcile this with volumetric and other data, the implication being that the real figure may in fact lie somewhere between 2% and 4%. That debt has escalated is beyond dispute, having increased from $7 trillion in 2007 to over $31 trillion today. Together, soaring debt and faltering growth are a nasty combination, and suggest that China may now be borrowing upwards of $4 for each dollar of growth. But the really worrying indicators are more nuanced.

For a start, and as we know from Western experience in 2007 (the “credit crunch”) and 2008 (the “banking crisis”), excessive debt tends to result in a credit crisis well ahead of a solvency one. In China, there is unmistakable evidence of “creditor drag”. Chinese businesses are finding it increasingly difficult to get paid by creditors, and average payment times are increasing markedly. Creditors tend to pay late, when they do so at all, and often pay with credit notes or post-dated cheques rather than immediate money. This inevitably stresses the system, because even a sound business can struggle to pay its staff or its own suppliers or, for that matter, service its debts, if its creditors do not pay on time. In short, expanding payment times are an early (but serious) harbinger of deepening problems.

“Creditor drag” is just one of the warning signs that are starting to flash amber-to-red in China. Another of these, mentioned above, is falling debt efficiency, where more debt is needed for each incremental unit of GDP. This ratio seems to have risen to greater than 4:1, meaning that 4 units of new borrowing are required for each unit of growth. This is simply not sustainable.

A third warning sign is debt recycling, indicated by a rising proportion of new debt that is taken on simply to repay existing borrowings. A fourth lies in successive failed attempts to convert debt into equity. Meanwhile, Chinese banks’ bad debts appear to be rising rapidly, which in turn raises questions about capital adequacy, meaning that the ability of banks’ reserves to absorb bad debt losses is being undermined.

Another crisis-marker lies in capital flows, which have turned adverse in a very short time. Over the last year, in a drastic break with previous trends, the long-established flow of investment capital into China has reversed, with close to $600bn flowing out of the country during 2015, most of it in the second half of the year.

Unlike the West, where borrowing has tended to be channelled into boosting consumption and inflating the notional “value” of the housing stock, China’s folly-of-choice has been the use of debt to create capacity far in excess of realistically likely demand. The immediate effect of such behaviour is to drive down returns on investment, often to levels which are lower than interest rates on borrowed capital. This helps explain why China has tried to convert debt into equity – and also explains why it hasn’t succeeded.

There are, in short, increasingly persuasive reasons for anticipating a credit squeeze in China, with the likelihood being that this will segue, pretty quickly, into a full-blown solvency crisis.

Risk 2 – equity market exposure

It may, perhaps, not seem surprising that equity markets have risen strongly since the banking crisis, reflecting ultra-low interest rates and the injection of huge amounts of QE into the financial system. But I am indebted to Damon Verial for flagging-up a potentially very dangerous downside risk, one which has gone largely unnoticed by market-watchers.

This risk lies in debt-funded stock buy-backs by quoted companies. This activity has been a huge contributor to market strength, particularly in the United States. The point that Damon Verial has noted, however, is that stock repurchasing correlates remarkably closely with borrowing. In other words, companies are taking on debt to fund buy-backs. He has likened this to the mechanism which created recessions in the US in the 1930s and Japan in the 1990s.

The overall funding pattern is unlikely to be noticed either by equity investors or lenders, both of whom focus on individual corporate leverage, not on overall trends in borrowing and buy-backs. But the combination of weak earnings and cash flows, and downwards trends in both borrowing and repurchasing, suggest that US equities could be heading for a huge (“meaning recession-huge”) hit to the market.

If equity markets do tumble, the effect on the broader economy is likely to be serious, particularly in a context of “secular stagnation”. The Wall Street Crash of 1929 triggered the Great Depression and, six decades later, a slump in over-valued stocks marked Japan’s plunge into a deep recession which continues to this day.

Risk 3 – capital flows and the $7 trillion gamble

Alongside China’s looming debt crisis and dangerous downside risk in American equities, the third crash-risk that can be identified with a high degree of confidence is the likelihood of disruptive currency flows.

This problem began in the aftermath of the banking crisis, when investors believed that there were two near-certainties on the medium-term horizon. The first was that interest rates in the United States were likely to remain low for an extended period, implying that the dollar itself would weaken. The second was that emerging market economies (EMEs), most notably China, would continue to grow more rapidly than the developed economies of the West. After all, they had been doing so already for an extended period, and were not, at that time, hobbled by the kind of debt burden that was weighing so heavily on the Western economies.

This suggested a straightforward strategy, which has come to be known as “the dollar carry trade”. The principle was simple – an investor who borrowed cheaply in dollars to invest in EME markets could anticipate that the secular advantage of higher growth rates would be leveraged by dollar weakness, ramping up the gains that would be made when the time came to move back into dollars and pay off the debt.

This logic seemed seductive at a time when it was fashionable to wax lyrical about the “BRIC” economies (Brazil, Russia, India and China). Since then, three of the four bricks have fallen from a great height. Brazil has suffered from a combination of weak commodity prices, economic deterioration, and corruption on a gargantuan scale. Oil prices and politics have likewise undermined Russia. Though growth apparently continues in China, it is not reflected in corporate performance, largely because the borrowing binge has been invested in so much surplus capacity that profitability and returns on assets have cratered.

Just as the EMEs have fallen from grace, the dollar has strengthened, not weakened. Investors in the dollar carry, in rushing for the exit, have rediscovered the old adage that “when everyone rushes for the door, the door gets smaller”. The unwinding of the carry trade probably has a lot to do with the unparalleled outflow of capital from the EMEs that gathered pace throughout 2015.

No-one knows with any precision the scale of dollar carry exposure, but the best estimate, which is of the order of $7 trillion, suggests that less than 10% of exposed capital has so far been reversed out.

This “gamble gone wrong” is, like the US equities risk, “recession-huge”.

Risk 4 – the failure of “kamikaze economics”

One of the most glaringly misleading terms in international economics is the “lost decade”, since Japan’s recession has now lasted for 25 years. In a desperate attempt to break out of the cycle of near-zero growth, escalating debt and widespread deflation, the Abe government has adopted a strategy of massive stimulus, including QE on a vast scale and rapid increases in government indebtedness. When we include household and business debt as well, Japan is one of the world’s most indebted countries, with a debt-to-GDP ratio in excess of 400%. Indeed, and compared to Japan, even Eurozone debt worries pale into comparative insignificance.

By deferring a planned increase in sales taxes out to 2019, Mr Abe has essentially conceded that “Abenomics” has failed. Deferring the tax was something that Mr Abe had previously insisted would not happen unless Japan was hit by a Lehman-type catastrophe or a serious earthquake. The country’s current predicament bears the hallmarks of both.

Once again, we need to examine nuances within the broader picture, which in this instance involves trends in Japanese government bonds (JGBs). Large fiscal deficits have resulted in the very substantial issuance of JGBs – but who is buying these new tranches of government debt?

The answer, rather shockingly, is that nobody is. Investors are not lending to the Japanese state. Instead, debt is being “monetised” – meaning printed – by the authorities. A country which reaches this situation is in the last-chance saloon where its credibility and creditworthiness are concerned.

Without burdening you with too many numbers, let me explain what’s been happening with JGBs. The central bank (the Bank of Japan or BoJ), as we know, has been engaging in QE on a huge scale, buying JGBs with money newly created for the purpose. This has resulted in an expanding BoJ balance sheet, and increasing BoJ ownership of JGBs.

None of this is surprising – but the actual numbers are.

Back in 2008, the BoJ owned less than 7% of all JGBs outstanding. But this number has since risen at an alarming rate. By the end of 2013, the BoJ owned 18% of JGBs. Today, this proportion exceeds 33%. By the end of next year, almost half of all JGBs are likely to be owned by the central bank.

These numbers are frightening in their implications. First, the BoJ is buying – meaning “monetising” – enough debt to far more than cover the annual budget deficit. Second, it is also monetising existing debt as it falls due for redemption. No one is lending to the Japanese government, and investors are big net sellers of government debt. Japan is moving rapidly into a situation in which it is simply printing its borrowing needs, be they for on-going public spending, debt redemption or the payment of interest.

If this continues – or as and when investors work out what is going on – both the yen itself, and yen-denominated markets, will collapse.

Nemesis #2 – the populist backlash

Just as crash risk rises everywhere – from Chinese liquidity to American equities, via a Japanese end-game and a Sword of Damocles hovering over capital flows – the powers that be in the global economy now recognise that the economy is trapped in “secular stagnation”.

None of this is surprising in itself. Even the most rudimentary knowledge of economics will tell you that, under normal circumstances, the vast stimulus injected into the system since 2008 should have caused growth to soar to the point of overheating, with inflation rising rapidly.

Instead, we have stagnant growth, and price indices hovering between zero and deflation.

If an animal that has been injected with huge quantities of stimulants fails even to twitch, the implication is that the animal is dead.

A fascinating side-effect of economic stagnation is a populist backlash against incumbent elites. This explains the popularity of Donald Trump, and also explains the rise of Marine Le Pen in France, Geert Wilders in the Netherlands, AfD in Germany, Eurosceptics in Britain, Podemos in Spain, right-wing nationalists in Austria, Syriza in Greece, and populist movements right across Europe. Even the Chinese authorities seem to have been rendered powerless to tackle the country’s debt problems by the fear of labour unrest.

Though the immediate flashpoints often concern migration, history shows that economic hardship generally does provoke social unrest, particularly when coupled with perceived unfairness. The migration issue itself has an economic dimension, because workers fear that an inflow of migrants depresses wages. Young people are trapped in a mesh of high rents, out-of-reach property prices, job insecurity and a dearth of well-paid employment. The deterioration in the real incomes of the majority contrasts sharply with the soaring wealth of those at the very top. At least one self-made American billionaire has warned of “pitchforks” unless glaring inequalities are addressed.

Whilst this may be – and probably is – unduly alarmist, the scale of the popular backlash in the context simply of “secular stagnation” must make one wonder about what the public response will be if, as seems increasingly likely, the financial system suffers a major shock.

= = = = =

Here are some charts on secular stagnation, from SEEDS

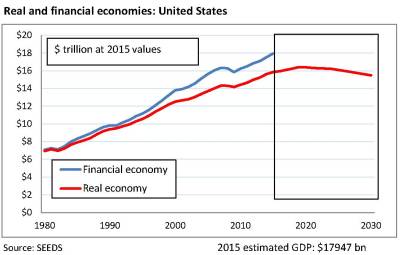

United States

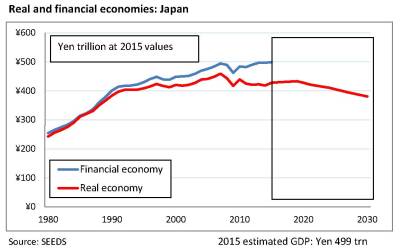

Japan

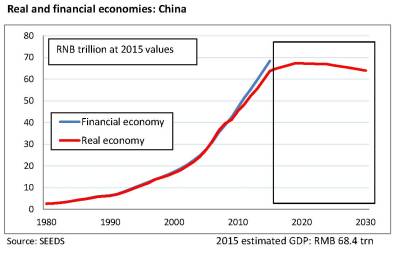

China

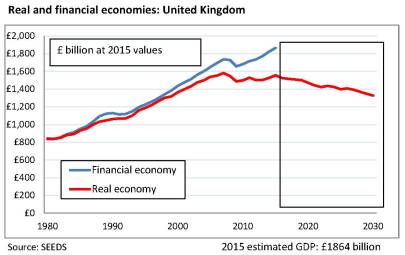

United Kingdom

Italy

I think that the roll out of Universal Credit (In the UK) – especially the application of ‘Conditionality’ for in work claimants will, to say the least be interesting.

Then what if we do vote for Brexit?

I am starting to wonder if The Conservative Party has been infiltrated by Trotskyites wanting to start a revolution.

I have absolutely no idea what someone like Teresa May is doing in a party that she herself described as “nasty”. The people I rate don’t seem to get to the top – I’m thinking particularly of David Davis and Eric Pickles.

The Brexit scare campaign is getting too silly for words. I’d like to quote to you an incisive comment posted by a reader on the FT website:

“Wonder what this guy [Philip Stevens] would be saying if he were 22 and looking down the barrel of working forever and renting forever.

“That’s what’s tearing the UK apart. I don’t think Brexit will fix this but it has been alluded to by proxy of immigration in the campaigns. And of course “Remain” have disgustingly tried to coax the boomers via threats of house price falls.”

Tim, another superb and incisive article. Very refreshing to read some original thinking. Thank you. I read your book ‘The End of Growth’ and it made a very deep impression on me, and last year I read Russ Roberts’ book ‘How Adam Smith Can Change Your Life: An Unexpected Guide to Human Nature and Happiness’ which revisited some of Smith’s ideas contained in ‘The Theory of Moral Sentiments’. There is no doubt in my mind that a small part of Smith’s writing – the invisible hand – has been hijacked to promote and bolster corporatism and greed. I find your articles and the comments of posters measured, thoughtful, interesting and invariably courteous. I am saddened that the mainstream media has so little to say about our national plight, other than by fostering falsehood and discussion of matters of little relevance. Earlier this year a writer in a leading ‘quality’ newspaper claimed that anyone using the term ‘mainstream media’ without irony was an idiot. I am guilty as charged, although in my defence I would make the plea that anyone using the term MSM may have been an idiot who has come to their senses and realises the extent to which the national press is part of the problem. With every good wish.

Thank you Kevin. I particularly appreciate your comments, because this article was hard work.

You are quite right about the hijacking of Adam Smith – corporatism and naked greed are hiding behind free market clothes. Karl Marx said in later life that “the one thing I know is I’m not a Marxist”. Likewise, Smith wasn’t a neoliberal!

The media has nothing much to boast about – some journalists are very good, but all too often they are cheerleaders for the establishment, notably so over Brexit.

I really like your analysis here:

THE PERFECT STORM

The economy is a surplus energy equation, not a monetary one, and growth in output (and in the global population) since the Industrial Revolution has resulted from the harnessing of ever-greater quantities of energy.

But the critical relationship between energy production and the energy cost of extraction is now deteriorating so rapidly that the economy as we have known it for more than two centuries is beginning to unravel.

Click to access Perfect-Storm-LR.pdf

That’s my core interpretation, and I can only add that nothing I’ve seen since has caused me to change my view.

There are plenty of analysts who are good at explaining the symptoms…. but as far as I can see only you can Gail Tverberg have identified the disease (Stockman is probably the best of the bunch)

It amazes me that so many smart people spend their time ranting at Bernanke and now Yellen ….

They refuse to ask the obvious question — why in the hell are the central bankers throwing a nuclear bomb into the economy to keep it going?

What is it they fear?

And if someone were to suggest that the problem is related to the end of cheap to extract oil — they’d dismiss that as nonsense.

As expected — nobody wants to go to that dark corner… because to do so can only result in despair… perhaps clinical depression.

7.3 billion people who eat only because we have petro chemical fertilizers that allow us to grow food in soil that is otherwise dead. When the economy busts up – the oil stops – and we starve.

Then you have 4000+ spent fuel ponds that MUST remain managed — that means spare parts and electricity.

Nope – nobody wants to go there. Everyone wants a Hollywood ending

Well – they will get one — it looks like The Road crossed with Apocalpse Now and The Titanic.

Well, many people only see what they want to see…….

Hi Dr Tim,

no.. I don’t think you’re being unduly alarmist, I think you’re being very level headed!

the fact you acknowledge that the cult of neo-liberalism is in the process of being ‘outed’ as a scam reassures me greatly,

I assume this is in part connected with the IMF economist’s report recently in the news,

it’s a shame the establishment should awaken from their ideological trance barely moments before we hit the wall but at least they will understand why they deserve to loose their shirts as all their corporate valuations, stocks, assets and stashed offshore currency accounts shrivel in value as the mother of all bubble bursts,

I wonder if the crash will be so spectacular that governments will end up taking previously privatised utilities back into public ownership at effectively pence on the pound?

I’d love to hear your take on UBI, universal basic income, we’ll need something when the majority are unemployed and the real economy needs rebuilding from the bottom up!

I find it hilarious that neo-liberalism has gone so far and boxed the whole global economy into such a corner that ideas of a somewhat left wing and libertarian nature seem the only way out of a right wing and corporatist disaster,

I was amused recently to hear Noam Chomsky interviewed and say,

“the one thing you can say about neo-liberalism is that it is neither new or liberal”

at least the end of growth may be slowing the acceleration of anthropomorphic climate change, it’s an ill wind that blows no good!

Thank you. Neoliberalism is, as you rightly say, a cult. Had Britain or the US (for example) been practising genuine market economics, the banks would have been allowed to fail, and the bankers would have been wiped out. A free-market state wouldn’t backstop property markets with cheap loans. “Miss-selling” would be treated as fraud. And so on. It is a form of hypocrisy rather than a real economic paradigm – and why invent a tacky version of something already defined, brilliantly, by Adam Smith?

I never quite know whether the establishment is blind to what is happening, or knows but keeps quiet about it. I think, if I had to guess, that the Americans know what is happening, but the British do not.

Some of the ideas being bounced around earlier this year looked like signs of desperation – negative interest rates and banning cash, for example. These idiocies seem to have slipped down the agenda just as “secular stagnation” has gained recognition – perhaps panic is giving way to resignation?

The late great Bob Monkhouse famously said “I’d rather die in my sleep, like my father – than screaming in terror, like his passengers”

And yes, the left has an opportunity here – I really never thought I’d see a self-proclaimed socialist get any votes at all in the US, and Bernie Sanders is the real shocker. Socialists elsewhere, though, are burdened by earlier sell-outs – for instance, Jeremy Corbyn doesn’t have to prove he’s different from Cameron, but he does have to prove that he’s different from Blair.

UBI is something that I’ll think through – putting this article together has been a daunting undertaking, but it needed to be done before moving on to future issues.

Very clear article Dr.Morgan. You have laid out our stark predicament. Given the situation, why is the federal reserve making noises about two rate increases this year? It would only force China to devalue its US $ peg and risk further capital outflows which would likely strengthen the dollar even more.

Thank you.

Unless Janet Y is being very subtle – create an expectation of a rise, then shock the markets by backing down – then the likelihood is that she really believes that ZIRP is crazy (as indeed it is).

The USD is seen, rightly or wrongly, as a safe haven, so is likely to remain strong even if she doesn’t raise rates. Also, buying pressure from those trying to escape from the “dollar carry trade” is likely to keep the dollar high anyway.

Likewise, I think capital outflows from China are a fixture – the Chinese credit-stretch problem that I describe is sure to be noticed by investors, even if it hasn’t been spotted already, and they know that the carry trade has to be closed out.

Many thanks for another very perceptive article.

I’ve just finished reading Robert Gordon’ s book: The Rise and Fall of American Growth. In the book Gordon says that growth has been on a downward path for the last forty five years (since 1970). The expectation that we will grow at a constant rate over time is in fact quite contrary to common sense. One of the core elements in Gordon’s case is that innovation has tailed off in the last forty years, despite what we may think, and has never matched the inventions of the internal combustion engine, electricity etc that drove growth in the late 19th century and early 20th. Innovation does not come along at regular intervals.

The various policies implemented by the central banks and governments are trying to target a state of normalcy that does not exist.

If you add to the arguments by Gordon the now present issues of demography and the added (neo liberal inspired) continuance of globalisation and the labour arbitrage this implies you have a pretty potent mix which, taken together with the increasing and enormous debt burden, gives us the sort of cocktail you suggest.

Like you I think there is no way out of this and the crash is inevitable. The conspiracy theorist in me might suggest that this is precisely what TPTB want because, when it does crash, the people are more willing to make sacrifices, albeit to those that are actually to blame.

Thank you Bob. I’ve not read Gordon yet – I must – but Kevin Phillips has been saying much the same for a long time.

I cannot see how some kind of crash can be avoided – though doubtless someone will try to find a nicer name for it, like “the great correction”.

I do wonder about post-crash resilience. Earlier generations had it – I still marvel at how my grandmother struggled on, with four children, first through the Great Depression, then during the war, after her street had been flattened by a 1000kg bomb in 1941. I just don’t know how her modern successors will cope with an economic slump of the size that I fear is coming.

A most interesting, well researched and worrying analysis.

Thank you, Alan, and welcome.

Tim,

I suggest a read of

http://smallfarmfuture.org.uk/?page_id=28

While you both have different perspectives I hope you find his work of interest

May I also suggest that you look at this site

http://www.resilience.org/

They may be interested in hosting your articles

Thanks – I’ve looked at these, and both are interesting.

Tim – please speak to Paul Hodges – you both bring clarity and sense!

http://www.icis.com/blogs/chemicals-and-the-economy/

An interesting blog, thanks, though I do not know much about the author.

another deeply incisive article Tim.

I must confess to using your stuff as a bit of a reference bible since your stint with Tullet Prebon

You are welcome – though I’m intrigued to know how it is useful!

i kept all those booklets you used to publish….always useful to flick back through for reference material in my own doomladen meanderings

Thanks for another great blog!! I particularly appreciated your comments about Adam Smith, who is widely misunderstood on both the right and the left. But you thoughts on the development of policy in support of speculators (value harvesters) rather than entrepreneurs (value creators) provide an especially powerful insight into the economic problems faced today!

Thanks – I’m not so sure that Smith is misunderstood (on the right, anyway) so much as misrepresented!

Policy favouring speculators rather than entrepreneurs is hard to get one’s head round at first, I find, but then it all slots together neatly.

Another fantastic post. Thanks Tim.

Thank you Sam – your comment is particularly appreciated as this was a tough one to put together!

Yes, A hugely incisive analysis. Can you not get this out to a wider audience? It needs saying loudly (and if necessary stuffed up politicians noses!).

Thanks David, and I wish I knew how! My contacts are only really in one party.

I did feel in writing this that I had somehow found some important themes. I doubt whether the politicos would listen……………

Hi Tim – you need to start some kind of think tank or research centre – call it something officious-sounding like “The Centre For Modern Economic Research”, and then get other like minded people who don’t have an agenda and vested interests in the ponzi economy to help you.

Rewrite the official statistics based on the real facts, present the problems we face openly etc..

As previous Head of Research at a respected corporate, what you say carries weight when presented properly. Join forces with people who have similar views e.g. the chap below (FT writer, chairman of chemicals research co). Speak to Money Week – the editor there shares many of your views – she might publish an article or three.

Also, write more articles in a way the general population can understand (you already do this brilliantly). Write a book. Speak to the BBC and make a documentary. Enjoy yourself doing it!

http://www.icis.com/blogs/chemicals-and-the-economy/2016/03/end-economic-supercycle/

http://www.icis.com/blogs/chemicals-and-the-economy/2016/05/central-banks-head-currency-wars-growth-policies-fail/

http://www.icis.com/blogs/chemicals-and-the-economy/2016/02/debt-financed-growth-model-reached-limits-admits-german-finance-minister/

Hi Dan

I’ve never started a think-tank, though I’ve written fairly frequently for one. I’ve done most of the rest, including re-presenting the stats and, of course, writing a book, “Life After Growth” (2013). I’ve had some conversations with my publishers about a new book. Is the editor of MoneyWeek still Merryn? She has published my work before, so would be worth contacting.

You have given me lots of food for thought!

Thanks Tim. Very interesting. You must sometimes feel like a voice crying in the wilderness!

I know there are many bloggers forecasting doom, but I wondered if you ever read Richard Duncan at http://www.richardduncaneconomics.com. I find him to be an incisive analyst about macro economics.

There is also Chris Martenson at http://www.peakprosperity.com who whilst not an economist, seems to have a good awareness of what is likely to come in the not-too-distant-future.

Thanks – I do indeed feel like the boy and the Emperor’s new clothes! I’m familiar with Chris Martenson’s work, indeed we have corresponded about these things.

My situation is that I think I’m right in my analysis, but my conclusions wouldn’t be touched with a ten-foot pole by anyone with influence!

Excellent analysis, Tim, as usual. Charles Hugh Smith is very good at putting some perspective to things and I would commend his latest offering: http://charleshughsmith.blogspot.tw/2016/06/the-structure-of-collapse-2016-2019.html

My personal belief is that a complete collapse in confidence in governments (already well under way, as you note) is going to ignite a worldwide sovereign debt crisis, and this is where your financial crash will begin.

Thanks. I admire Charles Hugh Smith, who brings admirable clarity to things that most of us find complicated.

It’s a moot point as to whether economic slumps bring down governments or the failure of regimes causes debt crises.

If you collect quotations, here was my alternative title choice for this article:

“A fresh wind blows against the Empire”

(Paul Kantner, 1941-2016)

Hi Tim and commentators above, any idea what we as individuals can do to insulate ourselves from the worst of the financial crash that Tim is talking about, please? Presumably the powers that be wiill ramp up the printing presses and create even more massive distortions until the inevitable implosion?

Any thoughts?

Insulation – please comment

Dan asks about insulating ourselves from the crisis that I believe is impending. Any suggestions will be most gratefully received.

My own first thought is that, as Dan says, the authorities will ramp up the printing presses, meaning high inflation and a loss of value of money.

My second is that governments will act without principle in defending a “national interest” which, as much as anything, is really their own interests. As you may know, in 1933 the US made the private ownership of gold illegal, punishable by a heavy fine and a stiff prison term. Owners were paid $21/oz in compensation, and were later allowed to buy their gold back – but at $28/oz.

I suspect there are long-standing plans for a “bail-in” if banks crash again, i.e. taking money from customers to offset bad debt losses.

So any form of insulation needs to be considered with this in mind……

Hi Tim

The obvious answer is physical gold, with a stress on the “physical”. You need to see it.

Second I would guess anything that is a potential store of value with a long term scarcity element; real estate ( try and find a bargain!); paintings; vintage cars; agricultural land.

I would think one should avoid anything with a “paper” value only: bonds; stocks and shares and any derivatives and bank deposits.

I think you’re right about the bail ins Tim but if this reaches down to ordinary depositors then I suspect it will be “pitchfork” time and real trouble will ensue; even the sheeple have a breaking point at which the truth dawns. I also suspect that in the case of a systemic crisis the bank deposit insurance limit might well slip for the simple reason it cannot be afforded; then things really will get sticky.

I can see the appeal of gold, and it would certainly have to be physical, as paper gold would be paper, not gold. But you’d need a safe to keep it in, and there’s always the danger of nationalisation (meaning, in this context, theft).

Scarcity value (and practical value) makes sense. It is possible to find good value real estate, if you know where to look, indeed I have ventured into this myself in a small way. Agricultural land is a good idea, but can be expensive, and surprisingly hard to find. Clearly paper assets are best avoided beyond what is required for immediate needs.

Bail-ins have been implemented – Cyprus comes to mind – but I agree that this would create anger. Of course, a political system that has ruled the roost long enough to become complacent might not concern itself with that risk.

One that concerns me is the banning of cash. The total value of bonds now trading at negative yields has just passed the $10 trillion mark, and some “experts” favour negative rates (“NIRP”). This sounds inoperable as things stand – why would a bank give you a mortgage if it had to pay you interest? People would obviously want the bigggest mortgages they could get, which sounds insane. Equally, why would you put money in a bank if they were deducting interest from you? So NIRP implies banning cash, but there would necessarily be some medium of exchange arise in its place, probably something physical rather than, say, Bitcoin. In the past, everything from cowrie shells to cigarettes have been used as currency…….

there are two aspects of buying paintings–vintage cars–rare stamps—and suchlike

1….is that they are beautiful to look at, and you get a kick out of owning them, which is fair enough

and 2… that at some point in the future someone else will want to take over their custody for a few years, with the same motivatiion of course, in exchange for large amounts of money.

but as is made clear, our future society is going to be one run on energy availability, to the exclusion of money in the sense that we know it.

If you own a food sourcein the inevitable future food crisis, (1 acres of land say) and somebody offers you a ferrari in exchange for it, what will your response be? Ask yourself the same question about a Michelangelo painting worth (in today’s terms) £100m. I suspect the answer might be the same.

and yes, beautiful objects have always been sought after and treasured since ancient times. But then the objects resided in the hands of wealthy patrons who commanded the energy sources. Kings wore gold crowns paid for by peasants like you and me.

Paintings and gold ornaments did not exist in thatched hovels..

We all have cars, because surplus energy allows us to.

Beautiful objects are a product of our “surplus energy” society. If you don’t have surplus energy, you can’t afford works of art in any sense.

Norman Pagett

Good points Norman. I admit to confessing to the belief in the “greater fools” argument where there is always someone out there who will pay more.

Thanks Tim, Bob, Norman and Nigel for your thoughts

For city dwellers, growing food isn’t an option. I’m aware that if society breaks down completely then we’re looking at things like weaponry etc, but then all bets are off, and presumably Martial Law will be enforced and anyone not behaving exactly as the military want will be quickly dealt with by trained soldiers.

Assuming the financial collapse happens without complete societal (is that possible? I’m guessing it is) what happens then? As Tim says, gold could be confiscated, and bank deposits will be used for bail-ins.

My gf has just sold her London flat so is sitting on cash (GBP).

Is that good timing? They say London property will crash, but won’t they devalue the pound and print money so CPI inflation hits 10%, and property prices could r50%+ pa? Isn’t the best thing to borrow as much as possible and wait for £100k to be worth the value of a mars bar?

Also, anyone have any ideas for funds to invest in?

For real assets, ‘m thinking also agricultural land, as you suggest, and also good quality machinery, home generators, solar power etc.

Great to hear others’ views.

Thanks Tim for another excellent article.

As to insulation, I would recommend getting as free from debt as possible. Personally, I don’t have gold – in a real world situation I can’t see many advantages in holding something I can’t eat or wear. I grow food and I wouldn’t trade food for gold – a bale of haylage maybe or muscle. My investments have been in myself, gaining as many practical skills as possible. I built my own house and I have some land, I keep bees, have a couple of housecows and we live entirely off grid but I know that when my big tank of diesel finally runs out and all the propane is gone my life will be a struggle without other people to share the burden. I can achieve a comfortable self-sufficiency but only while some semblance of normality exists because cutting wood for the Rayburn or hand milking the cow takes a lot of time.

Thank you Nigel. I admire what you have done.

I assume you acquired the land before prices soared, which was very far-sighted. Re your propane, I think we do have to assume that some kind of normality continues, though obviously the greater the flexibility (in this instance, fuel sources), the better.

More broadly, few people have the skills that you have acquired, so I’m not sure what others can do…………

you have done the ”right thing” Nigel, but ultimately the uk problem is 64 m people living in a country that can feed only 40 million—maybe not even that many. The food we do grow depends on hydrocarbon energy inputs, very few food producers know how to do it otherwise, in quantity. We expect food to be on supermarket shelves. When it isn’t all hell is going to break loose.

the last time we were self sufficient in food was in the 1800s i believe.

Come the crunch, numbers will reduce in some way, exactly how and by what method is impossible to guess at without going into very unpleasant thinking—so, like everyone else I prefer not to think about it….at least for most of the time.

That we are going to “downsize” is not in doubt, unfortunately the thinking on that would appear to be that it is going to be matter of minor inconvenience, and somehow our “wheeled society” will continue as usual. (Electric cars are one of the biggest jokes in that respect)….we will still be able to drive to work etc.

Maybe we should indulge in the Swiss insanity—and pay each other E2500 a month whether we work or not.

I have been, and continue be, a most grateful fan of your thoughts expressed in your writings. I can only begin to imagine the effort and sacrifice, thank journey very much.

I have been over the years an investor, lately a speculator. My question to you is how you envision any capital gains tax to adjust the gain for loss of value of the currency. The same issue with interest and dividends, as the after tax return has been for some time negative.

Thank you very much, Robert. After leaving the City, I started the blog (and wrote the book) to “keep my hand in”, but I find this stuff fascinating.

On capital gains tax (CGT), my point is that QE handed huge gains to the minority who already owned assets, so I feel that governments should have found some way of clawing this back in order to avoid the accusation of “enriching their friends”.

Please note that my article doesn’t criticise speculators, but does castigate governments who have made speculation more attractive and less risky than entrepreneurship. As individuals or as investors, we obviously respond to the incentives managed by government.

In Britain (for example), CGT is lower than taxes on income, which seems bizarre. One’s “family home” is exempt from CGT, and I accept that, but wonder if gains on property should not qualify for exemption until the house has been owned for a minimum of, say, 5 years. I’ve known people flip their “home” every year or two, pocketing tax-exempt gains each time, and don’t think that’s what the exemption was designed to promote. I’ve also long thought that interest income should only be taxed where it exceeds RPI, because otherwise the saver is being taxed on inflation, not “profit” or “income” in any meaningful sense.

As things stand, companies can offset interest expense against tax, but cannot similarly offset dividends. This tilts the playing field in favour of debt capital and against equity. Governments do seem – at long last – to be looking at this.

I’ve only now seen your blog, Tim. Like the others I commend you for it. Gail Tverberg looks with the same cold eye at the situation as do you, and a few others. Too many, like even Nate Hagens prefer to sugar coat the reality.

I have a few observations. I think the private debt burden will be “jubilee-d” or wiped off the books. It is strictly for a national emergency, not just for a few. It is only numbers in accounts, basically, so a reset would calm down the overheatedness we see today. It obviously will have plenty of complexities in actual operation. Chief among them will be how to compensate savers from the compensation debtors will get. Steve Keen has commented on that and he says the government would pay compensation commensurate with the debt reduction.

I can go on, but you get the idea. Banks would not be bankrupted as they would only lose the value of loans made out from thin air money, or nothing, in other words. We need solvent banks as government money is all fiat and can never be money until deposited in private accounts. Only banks have the accounts.

I understand banks cannot touch depositors money. So it is illegal for a bail-in without changing the law. Banks don’t need it as their loans have no components of their deposits involved. It’s called the Credit Creation Theory. Not sure why Cyprus occurred however.

This sort of possibility is one reason I believe it will not be debts, as such, that will create the crash, it will be because debts are using tomorrow’s real resources today. As we all should know, growth at 3.5% means a doubling of the economy every 20 years, and a doubling means ALL previous growth is doubled, since BC. This has to stop. Since growth is essential in today’s economies a stop will be unprecedented and is not planned for by anyone so far as I know.

On other issues, I’m not so sure Japan has a problem. I have been there and the government debt burden is invisible. Remember government debt is not a debt for the non government economy. It is a debt instrument whereby the government sells bonds to investors and stores them on accounts in their Fed reserve. For you and me such an account is a Savings Account, a sign of our wealth!!! So it is for investors in Government bonds. From the government’s point of view these bonds are debts, the same way a bank looks at your savings account. The government never spends these bonds, as being monetary sovereign, there is no use for them. So at maturity the bond is resigned back to the investor. No money changes hands, apart from interest earned.

Similar inappropriate language occurs with government budgets. A budget surplus, universally regarded as a good, is no such thing. It means simply that government spending fell short of the tax take. This “surplus” is a shortfall in money, and not any sort of real surplus. It is in fact a deficit that the non government sector has to make up, as the sectoral balances must add to zero.

These misconceptions bedevil the understanding of macroeconomics. So it’s easy to be wrong about how to address the deluge of credit available today. Real resources are the key to our future.

Thank you – I try to tell it is I see it.

You make a lot of good points here, so I’ll take some of them one by one. Wiping out private debt, thus letting borrowers off the hook, doesn’t explain the outcome of the lenders – if one side’s liability is erased, does the other side lose his asset at the same time?

If you are letting someone with a big debt, say $1m, off the hook, what about the prudent man – is he disadvantaged, i.e. he gets nothing whilst the reckless man gets his $1m debt erased? Then – if the reckless man used his $1m loan to buy, say, a yacht, does he get to keep it? If so, this sounds like big “moral hazard” to me – what is to stop people, in the future, borrowing to buy assets, in the knowledge that in extreme circumstances the debt will get written off whilst they get to keep the assets bought with it?

On bail-ins, laws can obviously be changed. In fact, I think they already have been in the EU, or maybe the attempt failed – I need to check. In any case, this was what happened with Cyprus. I remember the FT’s Martin Wolf saying at the time that it was naiive to think that depositing money at a bank was wholly risk-free, implying that the depositor was therefore an investor, potentially subject to loss. I find that thought rather scary, but I don’t doubt that governments, all-too-often “principle-free zones”, will let depositors be skinned in a crisis.

Opinions are divided about Japan – one leading commentator calls it “a bug in search of a windshield”. Rather than basing my case on the sheer scale of Japanese debt, you’ll notice I focused on JGBs. As things stand, there is no market in JGBs, or, to put it another way, the BoJ is the only buyer. It seems to me that monetising debt is disastrous, because the ability to create money at will to meet any spending the government feels like doing surely strips the currency of credibility – if that’s not how you see it, please explain.

The key point, as you indicate, is the impossibility of infinite growth within a finite resource set. Economics has never addressed this, as in economic theory resources are simply “assumed” to turn up provided the price is high enough. Economists are going to get a shock, I suspect, when theory collides with concrete reality.

In the words of the late great Yogi Berra: “In theory, practice and theory are the same thing. In practice, they’re not”.

That’s an excellent insight into why there can be no debt jubilee Tim.

Expanding on that…. if governments were to wave a wand and wipe out all debts it would literally turn the entire system on its head removing all the rules of the game….

And as we know — consistent rules are crucial to ensuring participants in the game.

If the players see that governments are willing to wipe out debt in a massive (or even minor) jubilee nobody would loan out a single dime — and the system would cease to function.

unfortunately pensions are just another form of collective debt.

debt-wiping cannot be selective

Thanks Thomas.. I must admit I can’t see how it would work.

As I see it, governments are trying to overturn the rules of the game – the system they’ve created can’t survive under the existing rules, but none of their new rules (negative rates, banning cash) look feasible.

Without a doubt governments are playing a dangerous game.

In China short-sellers are threatened with jail time. Failing corporations the world over a being propped up with massive loans allowing them to buy back shares to prop up their share prices. Central banks have plunge protection teams stepping when the markets get spooked (or try to adjust to reality).

Hedge funds are getting killed because they are confused by the new ‘rules’ of the game — i,e. there are no rules beyond doing ‘whatever it takes’

I’ve got an idea for a new fund.

Identify large companies that are not carry heavy debt loads… that are also providing weak earnings guidance….

Now by the rules of the game one would think such a company would be a short target.

But if you operate off the ‘whatever it takes rule’ you know that said company has a lot of room to borrow and buy back shares…. so if you are long and they step in with buy backs you win!

Essentially this strategy involves doing the complete opposite of what makes sense. Or what used to make sense.

Oh boy — we are really in deep deep trouble 🙂

Hi Tim

Your penultimate paragraph in reply above makes the point about finite growth. In a way this is the point that Robert Gordon is making.

The fact is that most economies didn’t grow at all for many hundreds of years and it is only quite recently that we have experienced “regular” growth. We expect the economy to grow at 2.5% year in and year out but this is quite contrary to common sense. GDP is largely based on population growth and productivity and, in the western developed economies at least, both of these are sharply lower than in the recent past.

Population growth does not get reversed quickly, even with contentious immigration, and productivity depends not so much on investment but on the far more elusive concept of innovation and, as Gordon says, that has been in decline for the last forty or fifty years.

As you say we are living in a fool’s paradise.

The Chinese are not alone in vilifying short-sellers, but actually these people are the canary in the coal-mine.

More broadly, governments have a vested interest in ensuring that neither equity nor property markets slump. Of course, King Canute (or Knut) had an interest in ensuring that the tide didn’t come in!

Stock buy-backs are discussed in my article – do look at the linked article by Damian Verial, it certainly convinces me.

Yes I did see that article. There has been plenty of coverage of this activity on Wolfstreet and of course Zero Hedge. All of these policies of course will end in tears… only question is when.

In the meantime — the best policy is to enjoy that dying days of BAU while we can…. because what comes next is probably not survivable. Or if it is – I suspect survivors will wish they were dead.

We are about to be unplugged. Forever

Indeed so. This situation reminds me of two rock tracks – “After The Deluge” (by Jackson Browne) and “Won’t Get Fooled Again” (the Who).

Bob

Indeed so. Unfortunately, the fools like their paradise, and governments want the fools’ votes. History suggests, though, that the public will discover reality long before governments do. Indeed, I think that’s already happening.

Tim, I did say my comment was partial, but that the debt jubilee is floated not by me but by Steve Keen, among others. He answers your concerns, particularly your comment on the prudent man. The debt jubilee is a one off, no second bites of the cherry, so to speak. The biblical one was every 49 years, but we only need one.

After that the collapse will come before we get to another suitable occasion. The best it can do is buy time, another story.

How about some reading? Cleanse the concept of it’s falsities:

David Graeber also writes about a jubilee in his book; “Debt, the first 5000 years”

as a last resort. And it is. Until then it’s just bankruptcies, but this is no solution to a nation wide mass crash. That requires a Jubilee.

I don’t get there’s a problem why the japanese government is buying government bonds when that is what any government does. It’s a safer place to save money for the investor, as the government guarantees it. Banks don’t. If investors want out its only because returns are better elsewhere, no? It is always the only buyer, by definition. Government debt is NOT a problem. Private debts are the problem.

The credibility of a [federal] government lies with spending only up to the limits of productivity at full employment, a Zero relationship with tax. It can never go bankrupt, except deliberately, and within the limit mentioned above can always buy its debts. We are basically in deflation today so how many $Trillions are there for the spending this side of runaway inflation?

The devil is in the detail…

For instance — there are hundreds of millions of people who rely on pensions — which are debts — so you wipe them out? What do they do for food if they have no income?

Wiping out debt means all banks are immediately out of business. How do they get back into business?

What about wealthy people who have much of their wealth tied up in bonds and equities (both are forms of debt) — what would they eat?

I trust you have seen Korowicz Trade Off paper on systemic collapse – if you pulled the plug on debt the entire global supply chain would collapse – very quickly. And like Humpty – you cannot put something so complex back together again. You break it – it disappears.

The complications and implications of enacting such a plan are beyond comprehension.

This is not 1397. Or BC209. This is 2016 – it’s an entirely different ball game.

Oh and if the central banks did this — and stated it was a one off – let’s say you had a 100 gold coins — would you be buying government bonds with them after the jubilee?

Only a fool would believe this was a one off.

Anyway – the debt jubilee is impossible — Steve Keen should surely know that.

Bloody hell! Why don’t you read my posts? I said only loans from thin air get wiped- in my earlier first post. Where did I say pensions? Your comment on Steve Keen says you are assuming what he said without bothering to listen. We certainly have to keep banks solvent. otherwise no money can get through to customers, no matter what the source. But I said that already. I’m not going to keep repeating the message, just re-read the posts before sounding off.

Like I said the devil is in the detail…

So pensions don’t get wiped out. What else doesn’t get wiped out?

What about bond holders? Do they get wiped out?

You are aware that pensions are big holders of bonds.

Banks must remain solvent. Ok

How do banks remain solvent if all loans on their books are wiped out? In case you are unclear when loans are wiped out that is the same as every single debtor of every bank defaulting on every loan on the planet — personal, auto, mortgage etc…

This would result in the collapse of the banking system. No?

I am quite confused by what you are advocating.

If you are not wiping the slate clean in terms of loans extended by banks. If you are not wiping the slate clean on corporate and sovereign bonds because that would wipe out pensions.

Then what loans are you wiping out?

Detail please.

My understanding of a debt jubilee is that all debts get erased.

Is this is a debt jubilee lite that you are suggesting? Again which debt gets wiped and which remains on the books?

And you have failed to address my concern that a proper debt jubliee would collapse the global supply chain.

I really like that axiom about the devil and the detail. When you start to think things through properly you find that they are often unworkable.

The problem we are facing is that we have run out of cheap oil. Feel free to explain how wiping out all debt would deliver cheap oil.

You are expecting an answer to this issue in a couple of paragraphs? It’s not possible. Better minds than mine are working up a scheme that may work out, details sorted etc. Your questions still don’t reflect digesting what I have already written, incomplete though it be.

There are various options in any Jubilee. None would suggest we trash the banks, so no need to go there. Steve Keen said, in the linked video, that the central bank would pay the commercial banks to wipe or pay off the outstanding mortgages, and the good guys get a cash injection in lieu. That would compensate them for any loss of housing values a jubilee might cause. My own version would be to do a book operation to zero out at least the mortgages [in 4 operations, aka double entry accounting] and the asset. The cash injection would still be paid to the good guys as compensation for the reduced value of their property. Banks can survive this, but not being in banking I can’t say anything about derivatives, wagers, etc. Someone else has to think this through. The banking system would not collapse, but it might be prudent to forbid derivatives and other financial wagers etc.

You can’t wipe out debt. No debt no money. Debt comes first!

as i see it–that problem with any form of debt jubilee is that someone–somewhere has got to implement it.

debt seems to be internationally enmeshed –in ways i certainly don’t pretend to understand—nevertheless if that is the case then there has to be some form of multilateral agreement on the process.

The Uk certainly couldn’t do it unilaterally.

so you have to visualise some benevolently minded individual /committee taking on this onerous task of dictating to everyone else as to what is ”good debt”—ie my mortgage—or ”bad debt”—your hedge fund. And then separating all the debt shades in between.

i have a very modest amount stashed in ”investments” spread world wide. I will not be best pleased if that comes under bad debt by the definition of some international committee.

as we exist in an energy economy, not a money economy, the ”debt” problem will sort itself out as our energy sources go into decline. Our money is worth only the energy that is in the system to back it up. When that goes, our money goes with it.

Obviously someone has to implement it. Possibly an emergency government, depending on the state of affairs when the SHTF moment arrives, will be forced to act. It will be part of a world wide chain reaction, not for just one nation i would think. Before that there’s bankruptcy.

Eventually when the grid fails we will all be impotent financially.

i do realise that this is a ”hole in my bucket” discussion

but when the shtf–we must bear in mind that those in any form of governmental control will–and must–behave like ordinary mortals….indulge in self preservation.

the niceties of international finance will not figure in their thinking…survival will.

therefore any implementation of control will inevitably be for the benefit of those with the physical ability to enforce that control to give them and their particular group the maximum benefit, at the expense of those less fortunate.

I’d go so far as to say the shtf crash will appear first in the USA, because their loonytoon politics seems entirely delusional, they are in a state of permanent energy deficit, while at the same time they wear the crown of ”most powerful nation”—for the moment.

when it happens, the house of cards will crash.

I fail to see how a debt jubilee would extend BAU.

Can you explain how it would help?

My take is that if a debt jubilee were to be announced — BAU would end — in less than a second.

Because that is the time it would take for billions of sell orders to be transmitted through the digital exchanges.

You cannot just blow up the entire system — and expect to save it. This is a massively complex interconnected piece of machinery — it cannot just be put back together once you smash it into pieces.

You may get your wish. The end of BAU. The planet mandates it and there is no escape either.

The extension of BAU is the objective of a Jubilee. A resetting of the clock. I can’t say what will or will not work. Considering this alternative a Jubilee will be a popular option, as long as the punters understand the alternatives.

I don’t see it that way. In fact I see just the opposite.

Remember the Lehman collapse? That was a mini Debt Jubilee.

Do you recall that the global economy seized up?

And you think that doing the same thing x 1,000,000,000,000,000 etc… is not going to implode the global economy?

The Lehman option was a popular decision, considering the alternatives

The alternative was a massive debt jubilee – like the one you are proposing now.

Because if – when Lehman was let go — the central banks would have stood by and done nothing — all debt would have been wiped out in short order — global supply chains would have collapsed — and civilization would have ended.

We had a peak at what a debt jubilee looked like in 2008 — and we did not like it. So we did not go there.

It would be no different if we went there now. It would solve nothing. It would hasten the apocalypse

Maybe I’m not explaining well enough? You keep showing you do not understand what a debt jubilee is, or should be.

In simple terms, debts are created by banks, like 97% of it all, without using a cent of reserves or deposits. Like game scores, there is no box where the numbers are stored for a game, they are just keystrokes in accounts conjured out of thin air. The sums created when paid back return to thin air. In the meantime the banks live off fees and interest due on the loan. A debt jubilee short circuits this and brings forward the end date, so the bank loses some of its fees and interest, but little else is affected. The solvency is not affected. IMO,The bankruptcy option is much more drastic. Obviously the banks become smaller, but that’s what we need. House values go down and we definitely need that to happen. Compensation has been discussed before.

Unfortunately … the real world is not the same as a game of Monopoly or any other game…

When you wipe out numbers as you suggest….. you collapse a very sophisticated, interconnected, fragile system.

And when you do that – it cannot be put back together again.

See Joseph Tainter – Collapse of Complex Societies https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Tainter

If it were so simple as resetting things by wiping out debt — why didn’t the central banks simply do that in 2008? Just toss kick the board over — pick it up — and start again.

They didn’t do so because they are ignorant or had another agenda [most likely]

You sound like you are not willing to learn. So what would be your solution to the debt overhang Tim keeps saying must be drastically reduced???

There is no solution.

And as we can see — the central banks have reached the same conclusion — more of the same is the only option.

I see that China added over a trillion dollars in Q1…. there is a story on Zero Hedge today about how the US has added enormous amounts of debt this year — and for each $1 of GDP it is now taking $10 of debt.

I fail to see how wiping out debt would kick the can – details are required yet not forthcoming.

On the other hand… I have seen what a pip of a debt default looked like (a pip as compared to what you are suggesting) when Lehman defaulted….

We were staring into the abyss… the only way we did not enter the vortex was — you got it Pontiac — the central banks backstopped all debts returning trust to the system —- and immediately allowed trillions of more debt to be piled on.

You are suggesting we do a Lehman on steroids, heroin, HGH, crack, and blow.

I don’t see that helping.

It’s your misconception that Lehman is comparable to a Jubilee. Lehman was destroyed, a Debt Jubilee would NOT destroy the banks. So the whole of your argument is nonsense.

Actually Lehman was not destroyed… Lehman was insolvent … and the Fed decided not to bail the bank out…. so Lehman declared bankruptcy …

‘In 2008, Lehman faced an unprecedented loss due to the continuing subprime mortgage crisis’ — https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bankruptcy_of_Lehman_Brothers

Bankruptcy resembles a debt jubilee…. the only difference would be one of scale… with a debt jubilee inferring all or most debts are wiped clean i.e. a comprehensive global bankruptcy.

This would not only destroy banks — but more importantly it would destroy the global supply chain.

As we saw in 2008 when the flea on the elephant was not bailed out — the world stopped — trade stopped…

The only thing that restarted it was the central banks announcing that they would limit the damage to the Lehman fiasco (or experiment?) …. they stated emphatically that they would guarantee every debt on the planet… that brought trust back into the system … trade restarted … the financial system unfroze… and we got back to BAU….

2008 provided the perfect opportunity to wipe the slate clean — instead of guaranteeing all debt the central banks could have stood back and just allowed every financial institution on the planet to collapse… they could have allowed trade to remain seized up which would have quickly resulted in the collapse of every company on the planet…

Millions of layoffs would have turned into billions… food would have stopped arriving at the shops… petrol stations would have emptied…. spare parts would have quickly not been available thanks to the JIT supply system… and we would have very quickly had total chaos … and complete collapse.

Thankfully the central banks did not try some sort of debt jubilee – we’d not be alive right now.

It would not have worked then – and it would not work now.

Plan B is the same as Plan A — as Japan has demonstrated — more of the same. Until at some point you push on a string …

You insist on getting it wrong, the core argument. Apart from that, sure, plenty of strife.

An argument is something that is backed with facts.

What you have done is stated an opinion. You have nothing to support your position.

On the other hand I have dropped a deluge of facts that support my assertion that a debt jubilee would immediately end BAU … literally within seconds of it being announced… well… in the time it would take a thousand traders to pound his fists onto the sell keys over and over again …

You insist on insisting I am wrong — but that’s all you do is insist.