LONG-ODDS BET OR A PORTFOLIO OF SCENARIOS?

An intelligent investor – as distinct from a gambler – doesn’t put all his or her money on a single counter. He doesn’t stake everything on a single stock, a single sector, a single asset class, a single country or a single currency. The case for portfolio diversification rests on the existence of a multiplicity of possible outcomes, of plausible scenarios which differ from the investor’s ‘central-case’ assumption.

This isn’t a discussion of market theory, even though that’s a fascinating area, and hasn’t lost its relevance, even at a time when markets have become, to a large extent, adjuncts of monetary policy expectation. The concept of ‘value’ hasn’t been lost, merely temporarily mislaid.

Rather, it’s a reflection on the need to prepare for more than one possible outcome. Sayings to this effect run through history, attaining almost the stature of proverbs. “Hope for the best, prepare for the worst” is one example. Others include “strive for peace, but be prepared for war”, and “provide for a rainy day”. There’s a body of thought which has always favoured supplementing hope with preparation.

Dictionaries might not accept the term “mono-scenarial”, but it describes where we are, working to a single scenario, with scant preparedness for any alternative outcome. The orthodox line is that the economy will carry on growing in perpetuity. Obvious problems, such as the deteriorating economics of fossil fuels and the worsening threat to the environment, will be overcome using renewable energy and the alchemy of “technology”, with “stimulus” deployed to smooth out any economic pains of transition.

The alternative scenario is that “growth” cannot continue indefinitely on a finite planet, that there’s no fully adequate replacement for the fading dynamic of fossil fuel energy, that the capabilities of technology are confined by the limits of physics, and that stimulus is a form of tinkering which can, at best, only bolster the present at the expense of the future.

There’s a duality of possible outcomes here, where we can indeed “hope for the best” (meaning continuity of growth) but should also, to a certain extent at least, be “prepared for the worst” (the ending and, by inference, the reversal of growth).

Those of us who understand the accumulating evidence favouring de-growth have a choice. We can act as latter-day Cassandras, predicting collapse, or we can think positively, contributing to the case for a “plan B”. The latter is the constructive course.

The centrality of growth

This won’t be easy. The ‘D-word’ – de-growth – is the great taboo. It’s the one contingency for which we have no preparedness, and of which we have no prior experience.

There’s a reason why, in the story by Hans Christian Andersen, only one small child blurts out the reality that the Emperor’s new clothes don’t exist.

Nobody else wanted – or was prepared to risk – challenging the collective mind-set, however mistaken that mind-set might have been. If the child had possessed wisdom beyond his years, he might have presented a solution (perhaps a better tailor) at the same time that he laid bare – so to speak – the problem of the imaginary garments.

The idea that growth might have ended is one of the most emphatic ‘no-go areas’ of our times.

Everything else, you see, is manageable. Incumbent governments might be replaced, large parts of the financial system might swoon into crisis, and the fashionable industrial sectors of the day might become old-hat. All of this has happened many times before, and we’ve coped. So, for that matter, have we emerged from those temporary interruptions to growth that we know as ‘recessions’ and ‘depressions’.

What hasn’t happened before is the cessation and reversal of economic growth.

Economic growth is the universal panacea. It pays off our debts, holds out hope for a more prosperous future, builds investment pots for retirement, bails us out of our own collective follies, keeps the public happy, allows new governments to promise success where old ones have failed, and creates new commercial titans to replace those whose day in the sun has passed.

Collectively, we pride ourselves on our ability to handle change. We can indeed cope pretty well with linear change, so long as the economy’s secular trajectory remains one of growth. Ideology is flexible, and has moved through feudalism, mercantilism, imperialism, socialism and Keynesianism in a sequence in which ‘neoliberalism’ is but the most recent fashionable “-ism”. In business, as on the catwalk, fashions change, and there’s no reason why the current ascendancy of “tech” should prove any more permanent than the earlier pre-eminence of textiles, rail, steel, oil, petrochemicals and plastics.

There’s nothing here that can’t be managed.

The ending of growth, on the other hand, is the one twist that invalidates assumptions, and wrecks systems.

It’s been said that ‘if God didn’t exist, we’d have to invent Him’. Theology is way off-topic here, but we can say, in a similar vein, that ‘if growth didn’t exist, we’d have to invent It’.

It’s arguable that, for more than twenty years, we’ve been doing exactly that.

The end of growth – breaking the taboo

If we look at situations objectively and dispassionately, the case that growth is ending is persuasive. It’s certainly a scenario against which it would be wise, if it’s possible, to ‘hedge our bets’.

The Limits to Growth (LtG), published back in 1972, made the lines of development clear, reaching the rational conclusion that there’s only so much energy use, so much resource extraction, so much pollution and so many people that a finite Earth can support.

Subsequent evaluation of intervening data underscores the prescience of this analysis, and suggests that the hundred-year window suggested in the original LtG may have narrowed to the point where barely a decade, if that, separates us from the ending of growth.

We might think of the time-scales like this. LtG gave us, as an approximation, a century-long window in which to adapt. Almost half of that – nearly fifty years – has passed since that projection was made. It was, and has remained, easier to dismiss or ignore this thesis than to respond to it.

There’s a strong case to be made that about half of that intervening fifty years has been spent in a precursor zone in which, though growth has continued, the economy has decelerated, a process that was always much more likely than a sudden, out-of-the-blue collision with finality.

In the narrower sphere of the economy, there really are no excuses for our failure to get to grips with the factual. The fact that the economy is an energy system is surely obvious, since nothing of any economic utility can be supplied without it.

So, too, is the operation of an equation which sets absolute energy access against the proportion of accessed energy – known here as the Energy Cost of Energy, or ECoE – that is consumed in the access process.

The idea that, far from being material and subject to physical limits, the economy might instead be immaterial – and governed by the monetary artefact created and controlled by us – has never been more than an illogical conceit, tenable only whilst another dynamic (that of energy) kept the growth process rolling.

History, and the laws of physics, combine to demonstrate that the dramatic growth in the size and complexity of the economy that has occurred since the 1770s was entirely a property of the use of fossil fuels. If we look, not at the finality of quantity but at the limitations of the value capability of that resource, it was only a matter of when, rather than if, we would reach the limits of that growth-driving dynamic.

The equation that determines the way in which we turn energy into economic prosperity has become constrained, both by the finite characteristics of fossil fuels and by the limits of environmental tolerance.

The solutions offered conventionally for this predicament are, to put it very mildly, far from wholly persuasive. Essentially, we’re told that REs can take over from fossil fuels, with any associated problems overcome by the relentless power of technology.

Far from being assured, this transition is very far from proven. The efficiencies of wind and solar power are governed by laws which set limits to their capabilities. Best practice is already pretty close to these physical limits to efficiency.

Renewables, though important, seem unlikely to repeat the fossil fuel experience by giving us quantum changes in available energy value. Their expansion makes vast demands on natural resources which, even if they exist, can only be accessed and put to use using legacy energy from fossil fuels. Most of this legacy energy is already spoken for in a society that insists on channelling the vast majority of it into consumption, rather than investment.

We’re unable, albeit for wholly understandable reasons, to redeploy much legacy energy from consumption into investment. We seem similarly unable to accommodate our practices to the intermittency of energy supply from renewables.

The resource demands of batteries are the additional weight that could break the back of the feasibility camel. Batteries are never going to give us the energy density – if you prefer, the power-to-weight ratios – of fossil fuels in general, or petroleum in particular. Storing petroleum energy in a fuel tank is cheap, reliable, and needs only steel. No amount of extrapolation from positive trends is going to assure the same result for batteries.

The difficulties with REs mean that we might need to ‘think the unthinkable’. It might transpire, for example, that cars and trucks are products of the fossil fuel economy, and that a society powered by electricity must develop alternative modes of transport.

An economy based on electricity is certain to be different from one powered by fossil fuels.

There’s a strong likelihood, too, that it may be smaller.

A case-study

We can hope, then, for growth in perpetuity, but this outcome isn’t guaranteed, or even particularly probable. There’s a compelling case for preparedness for the alternative outcome of de-growth.

What, then, could or should we be preparing for?

The best way of answering this question is to explore what de-growth would mean. The following analysis looks, as an example, at a single economy. The methodology is the SEEDS economic model, which is based on the principles of (a) the economy as an energy system, (b) the critical role of ECoE, and (c) the subsidiary status of money as a ‘claim’ on the output of the ‘real’ (energy) economy.

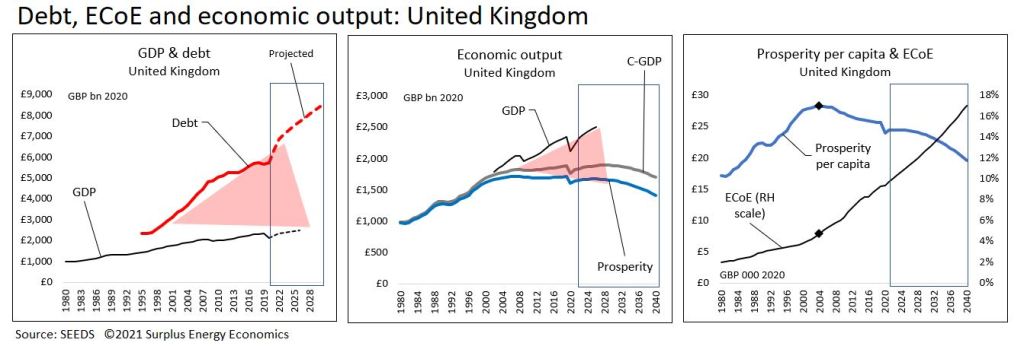

At the level of the national economy, explaining this requires two sets of charts. The example used here is the United Kingdom, but it cannot be stressed too strongly that this interpretation is in no way unique to Britain. Similar patterns – differing in detail and timing, but not in broad thrust – show up in SEEDS analyses of other countries.

Starting with conventional aggregates, we can see how a big wedge has been driven between GDP and aggregate debt (which includes government, businesses and households). Stated at constant 2020 values, British GDP increased by £400bn (24%) over two decades in which debt increased by £2.8tn (196%).

Because GDP, measured as activity, is inflated by credit creation, this process has driven a corresponding wedge between GDP as it’s recorded, and underlying (credit-adjusted) economic output (C-GDP). The gap between C-GDP and prosperity, meanwhile, has widened as ECoE – which makes a prior call on economic resources – has increased.

Switching from aggregates to their per capita equivalents, we can further see how prosperity per person, again expressed at constant 2020 values, has deteriorated since an inflexion-point which occurred in 2004, when British trend ECoE was 4.7%.

This deterioration in prosperity per capita has been comparatively gradual, such that the average British person was £4,300 less prosperous in 2020 (£23,900) than he or she had been in 2004 (at 2020 values, £28,200). That’s a 15% decline, spread over sixteen years, which might not sound too bad.

But the big leveraging factor in play is that, whilst top-line prosperity has been decreasing, the estimated real cost of essentials – combining household necessities with public services – has been rising. This increase can be expected to continue, not least because many essentials are energy-intensive, which ties their costs to the rising ECoEs of energy.

The result is that discretionary (ex-essentials) prosperity is falling a lot more rapidly than its top-line equivalent. On this basis, the average British person became poorer by £5,300 (32%) over a sixteen-year period in which prosperity itself declined by £4,300 (15%).

The middle chart below compares deteriorating discretionary prosperity per capita with an inferred measure of actual discretionary consumption. This shows a widening gap, indicating that a large and growing proportion of discretionary spending has become a function of credit expansion.

Finally, this trend can be tied back to the aggregates by comparing prosperity with total debt, and with the broader measure of financial assets, essentially the liabilities of the non-financial sectors of the economy (government, businesses and households).

Allow a Little Old Guy’s Reflections?

I put together a few days trip to the North Carolina mountains to show my sister and her husband and my children where our family came from, and the physical conditions which moulded them.

*We started at the King’s Mountain National Military site, which was the decisive Revolutionary War battle which drove the British out of the South and eventually led to the surrender at Yorktown, Virginia. That battle was won largely by the ‘Overmountain Boys’ who came across trackless mountains to fight the British and their allies among the colonists. I posed the question: “why were the Overmountain Boys willing to spend days crossing the mountains to fight the British?”. Nobody knew. Later on, we visited the Museum of the Cherokee Indians. A very large sign contained the proclamation by King George that the land west of the mountains was ‘reserved in perpetuity for the Native Americans’. And now you know: it was all about land (and the threat of the British commander to hang the settlers west of the mountains).

The population at that time was a tiny fraction of what it is now. And people were fighting desperately over land? Let’s talk about LTG and rising ECoE again, this time in sober language.

*I live a sheltered life, and it is easy to overlook reality. But driving short distances on Interstate 85 near King’s Mountain reminded me that automobiles are a small part of our problem. It seemed to me that half the vehicles were trucks (lorries, to you guys), and probably 85 percent of the tonnage thundering down the highway was ‘stuff in trucks’. Leaving Charlotte, NC and heading for home I was part of 5 lanes of traffic each way, mostly carrying ‘stuff’. What I see, just below the surface, is the world that fossil fuels have created. And that world cannot last.

*We stopped for lunch at a very nice little restaurant by a lake which features healthy food prepared and served by handicapped people. Somebody had left a section of the New York Times which bemoaned the absolute dominance in US movies of the Disney blockbusters: the triumph of formula escapism. I reflected that Walt Disney himself discovered a couple of things. One was nostalgia, as illustrated by Disney World. But more important was the sanitization of fairy tales. If you have ever taken a look at Grimm’s Fairy Tales, you know that they are the opposite of escapism. They are grim warnings to the young about the hazards of life. Part of Disney’s genius was to take the basic stories and turn them into ‘happily ever after’…no matter the peril, ‘your prince will come and save you’.

That’s enough of an old guy complaining…but I just see a society on the brink.

Don Stewart

Don, your remark re: the amount of trucking reminded me of the best companion art to 1972’s LtG that I know of:

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0085809/

Koyaanisqatsi – “life out of balance”

Tagio

I agree wholeheartedly.

Don Stewart

Reading through the last dozen or so comments, I can only reiterate that I agree with Don on a halved population being better for average well-being given scarcities and environmental damage. Plus I agree that China is trying to stop free market blow ups. Plus I agree on discretionaries likely the weakest link in equity markets. National debt payments will be printed when needed. The house of cards is shaky, but timing is unknown for the various collapses of fiat currencies.

One of the most frustrating things is that, even if we could find workable solutions, some countries – most obviously, Britain and America – wouldn’t implement them. Obstinacy and neo-liberalism are a fearful combination.

It was said, back in 2008-09, that “banks were fine – up until the day when they weren’t”.

That applies to markets, and to certain economies. I think we now know how much of this plays out.

Tim Watkin’s latest post makes interesting reading.

https://consciousnessofsheep.co.uk/2021/09/26/the-march-of-folly/

So is this article from Wolf Street.

China is clamping down on energy use, not least because the price of LNG has jumped to over $27 per mmbtu, from about $6 a year ago.

Tim, that is worrying in the extreme. Systems appear to be failing.

Upstream producer price index is experiencing 20% inflation year on year. This is effectively, tomorrow’s consumer price inflation.

I begin to suspect that many lofty plans for renewable or nuclear energy transitions, will prove impossible to implement, because the systems that supply the components and materials are failing. Utility solar power costs are up about 20% this year and wind turbines face a 10% cost increase. These products are energy and materials intensive and depend heavily upon low cost coal based energy and cheap (often forced) labour in places like Xingjiang. It may be that it is impossible to supply the products needed in the volumes needed for the green new deal energy transition, regardless of price. The Chinese cannot sustain production levels as they are, let alone the 10 fold increase that will be needed to affect the energy transition by mid century.

And for some bizarre reason, the western world is incapable of building new nuclear reactors to the sort of timescale and price that it could in the 1970s – some 50 years ago. We are paying about 10 times more for new nuclear reactors than we should be, based on production prices back then. Our inability to do this is absurd, given that it was done fifty years ago, with far less advanced manufacturing tech than we have available now.

Collectively, this leaves us up shit creek without a paddle. I honestly cannot see a way out of this now that doesn’t involve a lot of human suffering and huge reductions in living standards. I still hold out hope that western governments will pull their heads out of the sand and get on with a massive nuclear new build programme. But the time to have done this was the 1990s or early 2000s. Western governments have spent thirty years sitting on their hands.

A lot of this has been predictable – and predicted – for a long time.

ECoEs have been rising, growth has been decelerating towards zero and negative, and the geniuses running things have said we should ignore this stuff, assume a renewables replacement for fossil fuels, and keep pouring money into the system.

The results have been inevitable – supply shortages, rising inflation, ever-worsening financial risk. ‘Blame it all on covid’ is simply not credible, as any number of pre-covid data series amply confirm.

My focus now is on a serious of connected issues. One of these is discretionary prosperity, as the cost of essentials keeps rising whilst prosperity declines.

This will feed in to financial markets, where I’d expect discretionary (“cyclical”) sectors to lead markets downwards. A weak economy is good for markets – because it keeps rates low and falling – until the economy gets so weak that payment streams start to fail and the economy/markets inverse relationship snaps.

Timing that “snap-back point” has become the biggest call.

Third, some economies could crater, and the West isn’t immune to this. I doubt if anyone yet has this on their radar screens.

China’s action to limit/reduce energy consumption seems to be extremely important. Isn’t this an indication of something really serious? Shouldn’t it be highly alarming to the global economy? Shouldn’t it make headlines internationally?

I have often thought that Chinese government actions in the energy arena have been misinterpreted by many in the West. Chinese coal production has been on a plateau of 3.5GT per year since 2011. It represents about 60% of total energy consumption in China and more coal than the entire rest of the world is able to consume. The Chinese mine as much coal as the rest of the world, from reserves only half the size of the US. The average depth of mines is now 600m. Chinese coal is growing more expensive. Gail Tverberg has written about the prospects of a peak in Chinese coal production in the near future.

Not only has it proven difficult for the Chinese to increase coal production, but the sheer scale of their energy consumption makes it difficult to substitute other fossil fuels. They would need the entire world’s production of natural gas to supplant coal as the dominant energy source. Domestic natural gas production is only a minor addition to their total energy needs and the scale of their energy needs makes it unlikely that LNG could provide anything more than a minor addition.

So Chinese actions in the energy arena need to be interpreted in this context. Their attempts to integrate renewable energy into their grid is heralded by many in the West as embracing an energy transition to Green energy. But to Chinese leaders it has the more practical function of reducing coal consumption in coal burning power stations – stretching a resource that is close to its realistic limits. Wind and solar power allow coal plants to act as backup powerplants. This cuts their fuel consumption by a third. The re has been criticism of China in its continuing construction of coal burning powerplants. But new coal powerplants are ultra critical units, with very high steam temperatures and thermal efficiency of 45%. They replace older saturated steam plants, with efficiencies lower than 30%. And the capacity factor of Chinese coal is falling, as powerplants are increasingly used as backup plants and fuel shortages often leave less efficient units standing idle.

Chinese policy can be understood as an increasingly desperate struggle against coal depletion. They are expanding nuclear capacity as rapidly as possible, with the lofty goal of constructing 1TWe of fast neutron reactors by 2100. But their nuclear build capacity will take decades to build up to that level. They are therefore using every means available to them to stretch the benefits of their limited coal production, until new nuclear reactors can be built at a rate that comfortably exceeds the decline rate of coal production. The fact that they are searching for ways of cutting power consumption (bit coin for one), suggests that they may be falling behind in this race.

Thanks. That article by Tim Watkins is an excellent explanation of how we got to where we are and I’m sure would make perfect sense to a lot of people who cannot understand what is happening to the world. The ruling classes seem completely out of touch with reality.

@Tony H and Dr Tim,

Tim Watkins’ analogy between the motorists today queuing at pumps and the run on the banks (eg. customers lining up at cash machines in 2008 in Newcastle ) is absolutely spot on. This should be all you need to quote , Dr Tim ,to any who try to discredit your work regarding the vitality of energy to our economic survival.

Thanks, though let me put another angle on this.

In the UK, and elsewhere, people are going to have to pay a lot more for gas and electricity (they’ll still be paying this, indirectly, even if governments opt for subsidy). Fuel might cost more, too. Inflation is already rising, and energy cost increases will feed through into the prices of other goods and services.

They’ll have a lot less to spend on discretionary goods and services. They’ll also find it harder to ‘keep up the payments’.

But most discretionary sectors are still planning for growth, and their stocks price this in. Likewise companies which rely on ‘streams of income’ from consumers – subscriptions, stage payments, etc, as well as credit.

Does there come a point – even without rate rises – where markets suddenly ‘get this’?

Or does “a little local difficulty” continue to convince?

In the meantime, this is the quality of reasoning to be expected from HM’s Opposition.

https://www.zerohedge.com/political/uk-labour-leader-says-its-wrong-say-only-women-have-cervix

The ruling classes could hardly be more disconnected from the real world. They seem to be going insane and are forcing that insanity onto all of us. Is it any surprise that they were blindsided by the unfolding energy crisis, given the parallel universe that they seem to inhabit?

I’ve no view on this, but I can only suppose that millions of people would prefer him to concentrate on fuel supplies, supply lines generally, and the cost of gas and electricity.

I steer clear of party politics, but I do suspect Mr Starmer would be Mr Johnson’s first choice for Labour leader.

“Rather, we need clear thinking about how we manage an irreversible period of economic shrinkage – something no living human being has had to contemplate.”

With some misgivings, I refer anyone who thinks along these lines to the current round of interviews with Heying and Weinstein, including this one:

What Humans MUST DO To Adapt & Avoid the COLLAPSE of Civilization | Bret Weinstein & Heather Heying

You will find, if you delve into their evolution based analysis, that they fault modernity for dealing with symptoms rather than causes. Thus, for example, medicine treats symptoms rather than asking the fundamental questions such as “why did this person develop atherosclerosis?”.

Their solution is a refocus of society and governance on providing opportunities for citizens to engage in activities which provide the experience of Flow. To beat a favorite dead horse of mine, one example might be a productive garden.

In addition, they will point out that human health depends on some stress which makes us more adaptable. The technical term is hormesis. For a good discussion of hormesis, see this interview:

There is a transcript available on Dr. Kara Fitzgerald’s website, and you can get there by going to Lucia Aronica’s twitter.

I oscillate between thinking that “of course, they are exactly right” and thinking “the level of debt will never permit us to walk away from the dysfunctional civilization…we are not the Maya” and thinking “modern people seek Flow by driving an electric vehicle to a gym where they engage with sophisticated machinery”.

If you do a little searching, you will also find interviews with luminaries such as Joe Rogan, plus lots of their own podcasts.

Don Stewart

The Chinese leadership have always operated via long-term plans wherever possible, so they were always going to transition to the next phase in national development once able. After raising the quality of their tech capability level and the qualifications of their people, (through patient decades of putting a generation through universities all over the world) they can now shift to more of a knowledge economy.

https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2021/9/27/the-next-shock-in-the-pipeline-for-chinas-economy-energy-crunch

Having moved enough people out of poverty, they no longer need to be the factory of the world and endure the pollution and destruction that brings, so their need for energy will reflect that by falling massively. For us though, that will mean not only continuing disruption in supply chains and the volatility in price that brings, but also a permanent and significant increase in the price of ‘stuff’ in general, as the new sweatshop countries will have to use more expensive energy regardless.

Trying to guess at the future, that would therefore mean some reversal of outsourcing for those importing countries with access to cheaper or the same energy price, but probably mostly adapting to doing without for most people, as inflation bites ever harder. At this point it would seem that for the most part, a fall in population (declining birth rates) with the accompanying pollution + general environmental destruction that entails is already happening. As Dr Morgan already said, energy-forced simplification of anything not absolutely necessary is a symptom we’re already seeing.

Globalization has really helped China, most obviously because the West has been happy to out-source employment and hand over technology. I’m not clear on how rapidly China plans to expand nuclear, but it would be an obvious course of action.

I suspect that, where Chinese investors are concerned, Beijng will seek to ‘make good’ but not ‘make better’ – domestic investors might get most of their money back, but won’t make a profit out of it.

Joe Rogan and the Hunter-Gatherers on The Feeling of Growth without Growth

go to the place where 2:25 remains. Weinstein and Heying explain that growth is no longer possible, and stealing from others who are armed with nuclear weapons or even nuclear power plants is no longer possible. So how does a species which is addicted to the feeling of growth adapt to the new reality? And they tell you what they believe is the answer.

Don Stewart

PS For the biology-phobic, much earlier in the conversation they talk about the contrast between extreme high- tech science and biology. Only a handful can understand high energy physics, but anybody can understand biology. Just prior to this discussion, they talk about the crisis in public education. The wealthy, in a largely anonymous, Neo-liberal society perceive that their ability to enhance the survival of their own genes in their children is not dependent on a good public education system. On the contrary, their own children have a competitive advantage if the public education system is poor, while their own children attend excellent private schools. You may find that argument persuasive or unpersuasive, but anyone can understand it.

Hello Don

I find the argument unpersuasive. Thank you posting the spot. I am sure you have come across the highly educated idiot in your life (many times), I certainly have. The rich buying the kids a better education only has an advantage if the social system stays the same, further their kids are taught much the same things as in the public sector, though to a higher standard which can be a trap as they will have greater faith in what they are taught and are much less likely to question it. That will seriously trip them up as society changes and what is and what is not an advantage changes.

An observation:- those with good educations are often good at exploiting existing concentrations of wealth, to start with their qualifications gain them entry to it. But where there was no existing concentration of wealth who do we find? think about who settled America, where the passengers on the Mayflower the best educated in Britain? or the settlers that pushed west, or the self taught mechanics that made so much of the industrial revolution? And how much of American popular culture did NOT come out of elite universities (most of it)? The highly educated tend to risk avoidance, their education gives them an advantage in a settled society, and a disadvantage in an unsettled society as it gives them little advantage but has still been a cost to them to acquire. Don’t expect much from them in the post peak society, look to those who can shift for themselves, they will create the successor societies.

I work as a science tech in a UK college and am frequently surprised by my greater ability to spot the bleeding obvious and to solve practical problems than the highly qualified people I work for. My background is in the building trades, forestry, horticulture, and podiatry, all very hands on problem solving jobs. So how did I end up a science tech? Ill health forced me to find light in door work, and I was the only one to apply for the job. Pay is notoriously poor for science techs so anyone better qualified can easily find a better paying job elsewhere, but I like it. PS I get a workshop to play with!

Regards Philip

We have recently had, in the US, several celebrated cases where rich people bribed universities to accept their less than stellar student children. I don’t know exactly what a television celebrity expects an elite university to do for her child…but she paid a lot of money for it. I suspect that these sorts of incidents probably steered their comments.

No argument about the value of experience as the teacher.

Don Stewart

Joe Rogan, part II

Later in the interview, they say that if people sense that growth has stopped, they look for scapegoats. If one takes that seriously, then Degrowth is not an answer. Instead, the answer has to be something like rechanneling growth from material quantity to quality. Those of you who are really old may remember the central role of Quality in Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance.

Don Stewart

Don S, what a fantastic book. One of my favorites along with Hesse’s”Siddhartha” and D H Lawrence’s “Plumed Serpent” and many others. Phaedrus’ existential struggle to find meaning in the cacophonies within his mind is one I’ve experienced and continue to do so.

I looked for the term credit-adjusted GDP. BUT I COULDN’t find a definition. I believe this is a critical concept, but it doesn’t appear to be used.

Can anyone refer me to any analysis of this idea?

Credit-adjusted (or, colloquially, ‘clean’) GDP is defined as “economic output at a constant level of credit over time”.

I believe it is indeed a critical concept, and has proved more useful (and more predictive) than conventionally-calibrated GDP.